Sporting boycotts were a frequent occurrence throughout the 1980s.

If it wasn’t the Americans and some of their allies refusing to participate at the Moscow Olympics in 1980, following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan – the Eastern Bloc reciprocated four years later at the Los Angeles Games – it was African nations withdrawing from the 1986 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh over the UK Government’s links to apartheid South Africa.

In most cases, the significant absentees diminished the events – and almost bankrupted the authorities in the latter case before billionaire businessman Robert Maxwell “rode to the rescue” in his own typically immodest words.

But there was one global competition – the 1982 World Cup in Spain – which was at the centre of British calls for a boycott, because of the ongoing Falklands conflict and the fact the reigning champions were Argentina.

It was ultimately unsuccessful, but not for lack of political effort in Whitehall.

Mrs Thatcher was no football fan

The official documents revealed that the UK government seriously contemplated withdrawing all of the home nations from the World Cup and Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, was a leading figure in the campaign against the British representatives going ahead with their matches.

No fan of football, she argued that it would be a small price to pay to avoid the prospect of a potential propaganda victory for the Argentinians and it was even claimed by the Government that some players had expressed “revulsion” at the thought of turning out against Diego Maradona & Co.

The tournament, which was the first to expand to 24 teams, was held in Spain in June with Italy beating West Germany 3-1 in the final.

Scotland, England and Northern Ireland had all qualified for the competition, though none of the sides progressed beyond the second round.

However, a directive from the sports minister Neil Macfarlane, sent just days after the Argentine invasion of the Falklands in April, made it clear that the Government wanted the three football bodies to withdraw their squads and there was some angry exchanges as sport and politics intertwined.

It stated: “I urge no sporting contact with Argentina at representative, club or individual level on British soil. This policy applies equally to all sporting fixtures in Argentina for the foreseeable future.

“These measures are wholly proportionate, given events in the Falklands.”

The initial calls were met with disdain by many in the football community. They pointed out that Mrs Thatcher had been equally opposed to the British team travelling to the Moscow Games, but they had done so and the likes of 100m gold-medal-winner Allan Wells had helped lift the country’s spirits.

However, the Government ramped up its criticism during May and there was a point, as hostilities raged thousands of miles away, when the possibility increased that the Scots, English and Irish might sit out the World Cup.

Mr Macfarlane stressed his growing concerns in a letter despatched to Thatcher in May and there was sense that attitudes were hardening.

He said: “Up until a week or 10 days ago, I have taken the line that it was up to the Football Authorities to decide whether they should participate.

“However, the loss of British life on HMS Sheffield and Sea Harriers has had a marked effect on some international footballers and some administrators.

“They feel revulsion at the prospect of playing in the same tournament as Argentina at this time.”

Mrs Thatcher made her feelings clear in a TV interview when she tartly declared: “We can’t tell these people [in football] what to do, but the lives of our soldiers will always be our highest priority.”

The football bodies stood firm

By the middle of May, the issue had reached the highest level of government when the Secretary of State for the Environment, Michael Heseltine, insisted that Argentina should be excluded from the tournament, not only due to their illegal invasion of the Falklands, but because it might “insult” Spain.

However, that was never likely to materialise and it actually offended other nations rather than bringing them together. For starters, the football governing body FIFA boasted a heavy South American influence under the premiership of Brazilian Joao Havelange and had absolutely no interest in excluding Argentina (not least because they were holders of the trophy).

The SFA, which had sent a Scotland squad to play Chile in a stadium in Santiago where thousands of dissidents had been executed by the Pinochet regime in 1977, stuck to its familiar stance they were only interested in football matters. And there was similar antipathy to the notion of a boycott from the FA, whose team were appearing in their first World Cup since 1970.

Eventually, despite all their huffing and puffing – and to the chagrin of Thatcher – the politicians were forced to concede the World Cup was one of the few bright spots in the grim economic landscape.

So the cabinet secretary Robert Armstrong informed the PM that other nations would not support the UK’s proposed boycott.

He said: “In this case, no other country would follow us in withdrawing from the World Cup. And Argentina would see British withdrawal not as putting any pressure on them, but as an opportunity to make propaganda: the United Kingdom, not Argentina, would be the country which was set apart.”

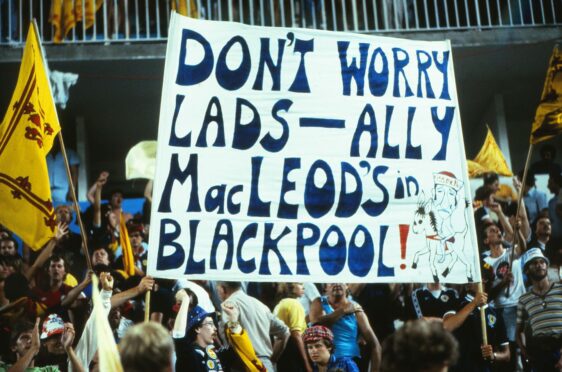

Sadly, once they all arrived in Spain, the home nations made only a fleeting impression on the tournament. Scotland beat New Zealand and lost to Brazil, but could only draw with the USSR and were eliminated on goal difference.

England won all their group matches against France, Czechoslovakia and Kuwait, but were knocked out in the next stage.

And Northern Ireland, despite the coup of beating hosts Spain and topping their group, were trounced 4-1 by France to end their hopes.

Yet, at least they all provided some memorable moments for their fans. Which would not have been achieved through a boycott.

More like this:

The trophies and the ‘toe-poke’: Dundee United great David Narey had a memorable career