The hostile environment which created the Windrush scandal was 70 years in the making – and may even be traced back to the attitudes of both the Labour and Conservative governments after the Second World War, according to a new documentary.

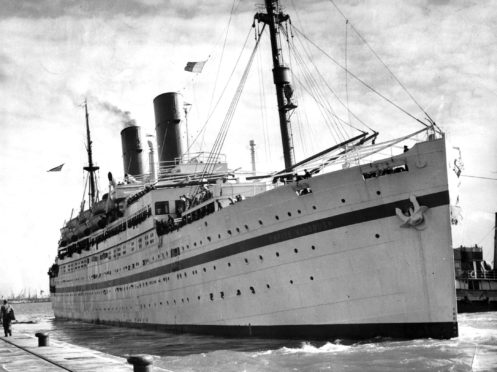

The BBC Two programme – The Unwanted: The Secret Windrush Files – looks into the background of the scandal which saw a generation of black citizens who settled legally after the Empire Windrush ship arrived from Jamaica in 1948 being told decades later to prove they had the right to stay.

The documentary says the scandal came from “a hostile environment that was 70 years in the making”, and looks at the various immigration measures which may have paved the way for it to happen.

Researchers looked at archive material including Cabinet papers, while historian and broadcaster David Olusoga also hears first-hand of the ongoing suffering of victims including grandfather Anthony Bryan.

He was detained and threatened with deportation to Jamaica despite having been settled in Britain for more than 50 years. He was unable to show documents proving his immigration status.

Many skilled men, including some who had fought for Britain during the Second World War, had arrived on the Empire Windrush in answer to a call to help plug the labour shortage.

Since then they had worked, paid taxes and made a contribution to the economy, culture and society.

Speaking of the documentary which he fronts, Mr Olusoga states the scandal did not “come out of nowhere”, and it is “intimately linked” to both a legal and a racial definition of Britishness.

Both the 1945-51 Labour government and Sir Winston Churchill’s Conservative government which followed it could be seen as having a negative impact on the Windrush generation, according to the programme.

It says that black people with British links had set sail on the Empire Windrush feeling like they were coming back home to the mother country.

It was unknown to them that politically they were seen as a serious embarrassment, and even described as an “incursion”.

Mr Olusoga later reflected “the government does not thank them for solving their labour problem, the government tries to work out how to make their arrival into a problem”.

Mr Olusoga said he was brought up to have huge respect for the 1945-51 Labour government for its role in the welfare state and the NHS, but “the other truth is that that government was committed to the imperial project”.

He said: “It was committed to an idea that the people brought to Britain to solve the labour crisis had to be white. It is painful.”

By the 1950s, the Conservative government was campaigning with the slogan “Keep England White”, according to the programme.

Mr Olusoga also suggests that a long-term and unchallenged presumption has been that unhappiness among poor white, working-class people at that time was the driving force behind government efforts to seek new immigration rules.

Mr Olusoga later said: “What the Cabinet papers from 1953-1955 of Churchill’s government show is that they had decided on a need to legislate before public opinion had shifted.

“On three Cabinet meetings… what they discuss is the need to focus public opinion on the formation of these black communities being a problem – but the public anxiety just wasn’t there.

“They (the Cabinet) fret about the fact that they would need to create the right public level of support in order to pass this form of legislation.”

He added: “It is too easy to blame the people at the bottom of society and not the people at the top.”

Some of those swept up in the scandal found themselves facing job losses and loss of access to services such as housing, healthcare and education.

Ministers faced a furious backlash over the treatment of the Windrush generation.

Home Secretary Sajid Javid launched a £200 million compensation scheme in April to “right the wrongs” suffered by people who faced difficulties demonstrating their immigration status.

Up to 15,000 eligible claims were expected to be lodged.

Commonwealth citizens who arrived before 1973 were automatically granted indefinite leave to remain, but many were not issued with any documents confirming their status.

Last year, the Government formally apologised in relation to 18 cases where the Home Office was considered most likely to have acted wrongfully.