The booming global satellite industry is among new sectors helping sustain the remarkable revival of one of Scotland’s last working underground mines, in a remote Highland village.

When the quartz sand mine at Lochaline closed in 2008, it was a devastating blow to the tiny community, where almost every household had a connection to the operation.

Now, as dumper trucks work day and night carrying its prized product from beneath the beautiful Morvern peninsula, a party is being planned to celebrate the 10th anniversary of its re-opening.

With positive geological prospects, the owners, backed by a Japanese glass-making giant and Italian mining experts, are confident Europe’s only underground sand mine can remain viable for decades to come.

And they are setting their sights on new markets, including the kitchen worktop industry, for a product once vital in the manufacture of wartime submarine periscopes.

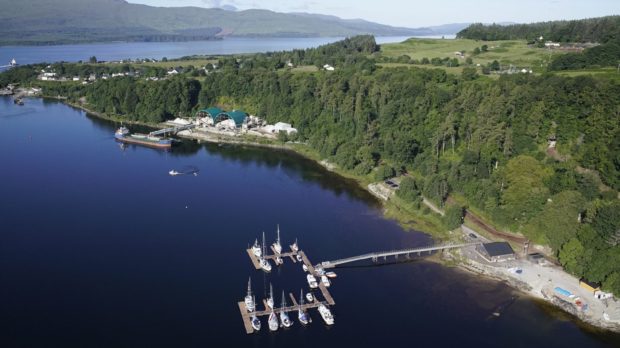

With a population of about 200, Lochaline lies on the shore of the Sound of Mull, at the southern tip of Morvern, which is home to around 320 people, scattered across 200 square miles.

Low in iron content, with exceptional whiteness, the vast deposit of silica-rich sand under the tree-clad land rising from the sea at the Argyll village is unique in the UK and ideal for making high quality glass products.

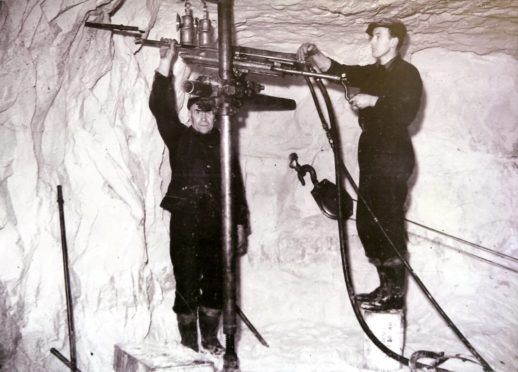

Know about since 1895, it started to be extracted in 1940, to meet demand for gun sights and periscope lenses during WWII.

The layer of ancient, hard basalt covering the deposit meant mining the sand, using tunnels dug straight into the hillside was the only way to get it out.

Lochaline’s coastal setting was ideal for shipping it to where it was needed.

Operations there continued into this century, until quarrying company Tarmac, the penultimate in a succession of owners, decided the mine was no longer viable and closed it.

The decision was a hammer blow for the local community, raising fears of a population slump and throwing the future of its primary school, hotel, shop and other businesses in doubt.

Ally Nudds, a shift supervisor at the mine, said few in the area thought it would ever open again.

Seeing the “writing on the wall” he left the mine and the area as operations were wound down, but returned there two-and-a-half years ago to work for its current owner, Lochaline Quartz Sand (LQS).

“It was a terrible time for the area when it closed, because just about every house in the village had some kind of connection with the mine,” said Mr Nudds.

“I really didn’t think we would ever see it open again.”

LQS, a joint venture between Tokyo-headquartered global glass manufacturer Nippon Sheet Glass (NSG) and international mining firm Minerali Industriali, re-opened the mine in September 2012.

NSG, which had acquired UK company Pilkington Group in 2006, making it one of the largest glass companies in the world, needed a source of high quality sand in Britain and the expertise of the Italian business to extract it.

The tie-up with NSG gave LQS a guaranteed customer as it re-built operations at Lochaline, starting out with around a dozen workers.

In 2017, a £1m expansion and an increase in the workforce to 20 was announced, as the firm, with £100,000 backing from Highlands and Islands Enterprise (HIE), started to develop new processes to make lower grade sand, previously treated as waste, marketable.

Around 30 people are now employed at the mine, where two new apprentices, including the first female trainee, started work this month.

Approximately 140,000 of tonnes of sand are mined and processed annually at Lochaline and loaded by a conveyor belt on to boats that moor below the site to collect weekly shipments.

Most goes to depots at Runcorn and Scunthorpe, in England, to be used by Pilkington in glazing and the manufacture of glass containers.

But other markets have also emerged amid increasing demand for Lochaline sand.

Veronique Walraven, office manager at the mine, said: “We have loads that go off to Fiven, a big Norwegian company that uses it to make silicon carbide.

“Silicon carbide can endure a lot of different temperatures and is used, among other things, for satellites. They also use it for body armour and other things.

“It’s one of our newer markets. We’ve been dealing with the company for a while, but they’ve been taking more sand in recent times.

“I like the idea of our sand being up in space.”

She continued: “We have another customer that mills the sand for use in the ceramics industry.

“We also deliver it to intermediary companies that sell it on. I know in one case we sold sand that went straight to the Harry Potter studios and was used in some movie or other.”

Ms Walraven said that, while the company was not looking to expand its operations greatly, it was keen to continue to diversify.

“For example, at the moment we are sending some sand away to see if it can be used to be made into hard material to make kitchen work tops – we are looking to go into that kind of market,” she added.

“We are also very much looking into ways we can make our business more green.

“One of the main things we do already is use closed water circulation, with all of it drawn from a huge underground lake.”

Lochaline is one of just three remaining working underground mines in Scotland. Gold and silver is being mined at Cononish, in Argyll, and the mineral barite is extracted near Aberfeldy in Perthshire.

The current face being blasted and excavated at the Movern operation lies about 590ft below the surface and around one-and-a-half miles in from the mine’s cave-like entrance.

The workings form an intricate tunnel network under the countryside, with the passages wide enough to accommodate the excavators and dump trucks that move through them.

While the exact total length of tunnels is not known, Mr Nudds said they would now stretch to more than 200 miles.

Next year’s planned party will be a double celebration, after Covid prevented the mine’s owners marking the 80th anniversary of its opening in 2020.