It’s been about 10 years since oil prices started to spiral downward, triggering a savage and prolonged downturn for the North Sea energy sector.

As people living and working across the north-east know all too well, the region’s whole economy is inextricably linked to the price of a barrel of crude oil.

The highs and lows may or may not – and usually don’t – match what’s going on elsewhere in the UK.

Of course, downturns are inevitable in the cyclical nature of oil and gas production.

Tens of thousands of jobs were shed

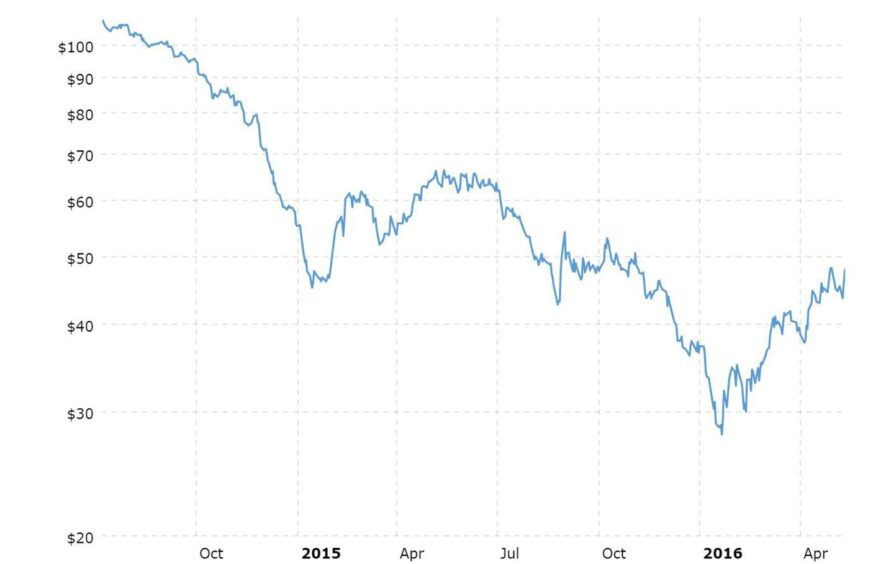

But the one we saw from 2014-2016 was particularly sharp and long-lasting.

Tens of thousands of jobs were axed on and offshore after oil prices started falling in the summer of 2014.

In a special new series in The Press and Journal, we take a deep dive into the circumstances of the downturn and how it impacted the north-east in all sorts of ways.

And we’ll explain why it was so very different than anything we had ever seen before.

Everything seemed rosy for the north-east economy when the price of a barrel of Brent crude oil reached about $115 early in the summer of 2014.

Property developers were cashing in on soaraway house prices, while hoteliers were also enjoying good times as Aberdeen maintained its run as the most expensive place to stay in the UK outside of London.

By the middle of June oil prices had surged to a nine-month high as turmoil in Iraq threatened the global outlook for production. Al Qaida-linked insurgents captured key cities in a region considered a gateway for oil and they vowed to advance on Baghdad.

Expectations for global oil demand, particularly in China, were driving up commodity prices.

No wonder then, that oil revenues for the Treasury were a key plank of the constitutional debate in that year’s battle for and against Scottish independence.

But in the world of oil prices what goes up inevitably comes crashing down again.

By September 8 Brent crude had slid to below $100 for the first time in 14 months.

Oil glut drives down prices

This prompted some members of producer group Opec to voice concerns about too much oil in the market.

But the world’s leading producers were reluctant to cut global output.

Meanwhile, Chinese and US economic data signalled slower-than-expected growth in the world’s top oil consumers.

Between June and December 2014, the price of Brent crude fell by 44% in one of the most dramatic oil price declines seen in recent history.

There was a slight improvement in the first quarter of 2015.

But oil prices continued their descent during the rest of 2015.

They hit a floor of below £28 in January 2016 before starting to pick up again.

Job slashing in the north-east oil and gas industry began in earnest in 2015.

In an article in The Press and Journal in June 2016, I reported how the collapse in fortunes of the UK offshore oil and gas industry caused tens of thousands of job losses.

And the figure was expected to rise to around 120,000 by the end of that year.

This total included “direct” redundancies in oil and gas exploration and production activities, as well as their immediate supply chain.

It also included “indirect” job losses suffered by companies exporting goods and services overseas and a knock-on “induced” impact on the wider economy, such as hotels, restaurants and taxis.

North-east hit hardest

The north-east bore the brunt of the colossal job losses, with special task forces set up to help people find new work.

This all came in the wake of the Wood Review, in which energy industry veteran Sir Ian Wood set out his vision for mitigating the impacts of declining production and an anticipated fall in investment across a maturing North Sea oil and gas industry.

The dawn of Opportunity North East

And in a direct response to the 2014-16 downturn, Sir Ian teamed up with other prominent figures from the business and public sectors to launch a new body – backed by a £50 million funding pot – devoted to diversifying and growing the north-east economy.

The Opportunity North East partnership has led major projects in the area since then.

Awareness of the need for economic diversification was not particularly new, of course.

The north-east’s decades-old dependence on the oil and gas industry was unsustainable.

But when the region escaped the ravages of the 2014-16 downturn it found itself in a brave new world. Governments around the world were finally getting serious about tackling climate change.

There could be no going back to doing business with no thought for its impact on the planet. Net-zero targets became the new normal and everyone had to play their part.

This made the upturn post 2013-16 unlike any other.

Oil and gas firms are having to find new ways of operating in line with net-zero ambitions, while they are also part of a wider transition to new forms of energy supply.

Fossil fuel production may be around for some time to come, potentially decades, but it is not part of the world’s longer-term future.

As in earlier downturns, thousands of people left the North Sea oil and gas industry in 2014-16.

But while in the past they returned to the sector in droves in the upturn, this time they were just as likely to change their careers, launch new businesses or seek work overseas.

Meanwhile, Scotland’s energy transition is creating many new “green” jobs in offshore wind as well as hydrogen, and carbon capture and storage projects around the country.

Business rates outrage

There was another major knock-on effect of 2014-16.

Firms from the hospitality, engineering, oil services and retail sectors in and around Aberdeen went on the warpath over huge increases in their business rates after a revaluation. It was based on an assessment of the north-east’s booming economy in 2015 – before the slump in oil and gas.

Some businesses faced rates rises of more than 100% amid the savage North Sea downturn.

The repercussions of this are still being felt.

And then came Covid

Oil prices plunged to new lows during the Covid pandemic.

When much of the world went into lockdown, demand for crude collapsed.

This put further pressure on a North Sea industry that was forever changed by the 2014-16 slump.

Conversation