We all know of the carnage in the trenches of the First World War, but civilian life had been disrupted too, with many working long hours in dirty conditions or in dangerous munitions factories.

The influenza outbreak of 1918 took a further catastrophic toll among military and civilians alike. The huge death toll left communities struggling, having little male labour.

The shortage of men would lead to the many widows and unmarried women not having families to maintain the social fabric of life.

This was keenly felt in the Highlands and Islands, especially with subsequent war memorials standing in an empty countryside.

It was not just the human fatalities but also of the hundreds of thousands of horses that did not come back from the war.

Farming had managed to increase production during the war and this gave them the experience to continue when less labour was available.

Food scarcity was still a concern in peacetime but the increase in production had taken its toll on soil fertility and some land would go back to grass.

Farm buildings, drainage and fences had fallen into disrepair and weeds increased in the drive for food and could only be reversed with more money and manpower.

However, one legacy of the war was the increased use of artificial fertiliser which helped maintain yields. As always, war helped speed up scientific advance which in the case of agriculture was in plant breeding and botanic sciences and in the increase on veterinarian science.

It was the use of the combustion engine which was one way the war differed from others before it. Many serving troops and women too began to learn about operating and servicing internal combustion engines and these skills would be transferred gradually to agriculture in the 1920s.

The war had seen the early tractors prove their worth and many farmers who had benefitted financially from the war took advantage of the new technology which improved greatly in the post-war years. The post-war surplus sales saw many ex-servicemen buy trucks and lorries and start haulage businesses which were able to deliver or collect on individual farms rather than produce having to be shifted to and from railheads.

Incidentally the surplus of lorries from the war had a detrimental effect on the nation’s manufacturers, who had increased production only to see sales plummet.

These engines powered a greater mobility for country residents be it a car for the farmer, a motor bike for the ploughman or buses for the wives and bairns.

For the troops returning they were promised a land fit for heroes and some landowners with vacant farms advertised them for let to returning servicemen.

At government instructions some estates and large farms were broken up to form smallholdings where the tenants could engage in intensive farming of fruit and vegetables, pigs, poultry and dairying. Other government interventions included the creation of the Forestry Commission.

Perhaps the biggest change in the countryside was the number of farmers who were able to buy their farms after the war.

The high casualty rate of young officers saw many landed families having to pay death duties for lost heirs. This saw many tenants being allowed to purchase their farm to help the landowners raised the cash to pay the exchequer.

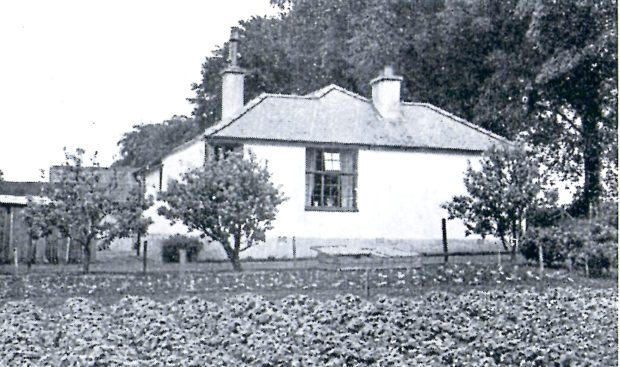

With cash made during the war the sitting tenants could afford to buy and for the first time the countryside saw owner occupiers on farms.

This desire to purchase their own farms was caused by a confidence given by the wartime government who supported UK farming in many ways during the conflict and the subsequent Agricultural Act of 1920.

However, this confidence was totally undermined by the Act’s repeal in July 1921.

This led to a price crash for agricultural commodities which led to a long period of depression both in agricultural and wider urban circles.

It would take another threat of war in the 1930s to see things turn around once again.