Harvesting is under way in many parts of the country as farmers reap what they sowed in the age-old season of hope and hard work. While the tensions of the season remain ever present, the harvesting technology seeks to lighten the load. Pete Small looks back to some of its origins

The sight of the mighty grain-munching leviathans is familiar, as they belch out stoor with drivers oblivious in dusty, sound-proofed, air-conditioned cabs, gobbling up huge acreages.

Operators must be on hand to monitor the monitors, watch the intake of the wide headers, empty the grain tank, even though they may not have to steer.

The machines must be self-propelled to get enough power to work the multi threshing systems, straw chopper and even drive the track systems.

This is in stark contrast to the first self-propelled combines of 80 years ago.

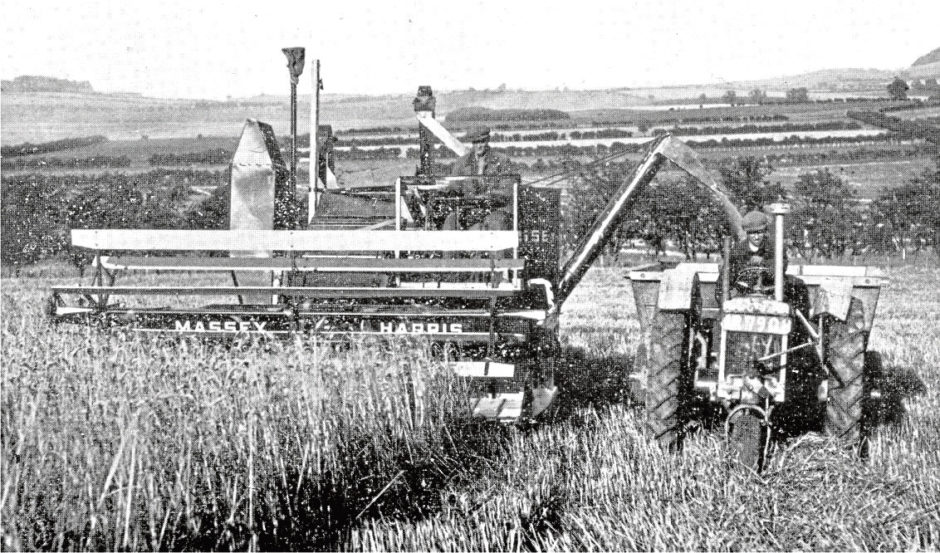

Canadian global giant Massey Harris is credited with introducing the first successful self-propelled combine in August 1938 when the company unveiled its No20 machine.

Massey Harris, like many other concerns on both sides of the Atlantic, had previous combine experience with numerous trailed models. Trailed combines dated back to the 1880s when huge teams of mules pulled them in California with the mechanisms driven by large land wheels.

Massey Harris’s combine guru, Tom Carroll, had begun to trial a prototype self-propelled one in Argentina.

This machine, known as the No19, quickly evolved into the No20. Finished in silver galvanised steel panels the machines were powered by a 65 horsepower Chrysler engine. Available as a tanker or bagger it came on steel wheels, rubbers only being an option at this time.

In two years of production 925 machines emerged from the firm’s New York Batavia plant, with some coming to work in the UK.

However, Tom Carroll was still not happy with it, believing it to be too heavy and expensive.

As a result, development work continued and in 1941 the first of the hugely successful No21 machines emerged.

It was available as the No21 with a canvass table and the No21A as an auger table. Again, tanker and bagger models were available on the 12’ cut machine.

During the Second World War when food production became so important the merits of all combine harvesters, trailed and self-propelled, were fully realised on either side of the Atlantic as significant numbers were imported through Lease Lend.

International Harvester – another global concern – was next in introducing a self-propelled combine, when in 1942 it launched its 123 SP model, which was a self-propelled version of the trailed type.

Even Marshall of Gainsborough also had an attempt with a rather poor underpowered machine.

After the war John Deere put its model 55 combine into production in 1946.

Another US concern, Oliver, was closely associated with Canadian firm Cockshutt, and Oliver tractors were marketed in Cockshutt livery – it is said Cockshutt combines were also offered in Oliver livery.

In 1946 at least one of these Cockshutts was brought over to work on a farm in Norfolk, with permission sought to import more in 1947 by John Wallace of Glasgow. These machines closely resembled the outline of Massey Harris combines.

The successful Gleaner line of harvesters introduced a self-propelled machine in 1950 prior to the Allis Chalmers buy-out in 1955. Minneapolis Moline were another concern whose machinery came over during the war, but it was 1955 before the firm launched a self-propelled combine which never saw use in the UK.

Meanwhile, Case offered several trailed combines with some coming to the UK. However it was the firm’s re-entry to the UK market in the early 1960s which saw its first self-propelled machines reach here.

Only the popular Massey Harris, International, Cockshutt and two John Deere 55s were the American representations in early self-propelled years.

The smaller size of UK farms and fields and spending power of farmers meant trailed combines were still very popular in post-war Britain right through the 1950s and into the 1960s.

The next step for European self-propelled harvesting was down to the continent’s own manufacturers with the first specially designed for damper conditions coming from Claeys of Belgium in 1952. Claeys’ MZ machine is said to have been inspired by John Deere’s model 55.

Claas was next in 1953 with the launch of its SF model.

Over the years other manufacturers followed suit with offerings from Fahr, Volvo BM, Viking, Dania and French-built Internationals. British-built combines included Ransomes and Allis Chalmers machines built at Essendine and the Fisher Humphries machines with their folding headers.

Today’s giants are a cut above all these.