Climate change concerns have transformed simple soil into the sexiest of subjects.

The imperative of storing carbon wasn’t even on the horizon back in the early 1930s when researchers embarked on unearthing what was to become a collection of 56,000 samples from across 15,000 Scottish fields, forests, moors and mountains.

But today a time capsule of row after row of individual jars stored by the James Hutton Institute (JHI) in Aberdeen is priceless as scientists consider future land use priorities, food security and resilience to environmental change in light of the climate change emergency.

You have to descend deep below what was once the Macaulay Institute for Soil Research, pass through locked doors and gain special access before you can step inside Scotland’s National Soils Archive.

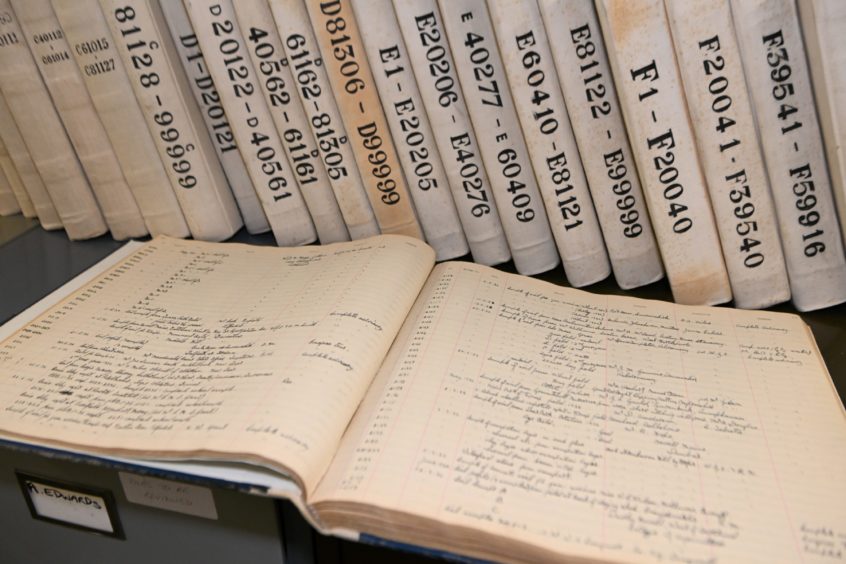

Here ledgers record the meticulous collection of the original soils in copperplate handwriting; racks of samples are meticulously filed; and records are kept from Scotland’s National Soil Inventory which sampled soil every 10km across the country from 1978-87 and the repeated survey at every 20km in 2007-09 .

The Macaulay, and JHI since 2011, is best known to the agricultural industry for the development of the land capability for agriculture system which is recognised by farmers, planners and estate agents as the official way of valuing land.

Impact

But the soil samples stored in the archive have a much wider significance as they give scientists an insight into past soil conditions and can be compared with current soils to investigate the impact of pollutants, pesticides, microplastics and antimicrobial resistance, and to see how soil carbon and the nutrient status of the land has changed over time in response to agricultural techniques.

The archive’s curator, Dr Jason Owen emphasises the relevance of the collection to current research priorities.

“We know about atmospheric carbon and carbon cycles and climate chaos. But the amount of carbon stored globally in soils is far higher than atmospheric carbon,” he said.

“It all feeds in to land use priorities and land management issues which are also being studied here at JHI.

“And they are invaluable to future scientists, as we don’t know what they will be looking at in another 50 years time.”

The archive’s manager, Gillian Green, is fiercely protective of the collection and individually re-potted all 56,000 samples in new containers – a process which took eight months. She also oversees the transfer of minuscule quantities from individual samples which are allocated to researchers.

She said: “They are treated with great care, and go nowhere without their unique seven-digit identification number.

“There has to be a valid scientific reason for any soil to be taken from the archive, and when we only have a small quantity of a sample left, requests have to go to a committee which decides it if can be taken as these samples are irreplaceable.”

Soil monoliths, representative of the different soil types in Scotland, and containing soil taken out of the ground and impregnated in a resin, are also on display in the vault, alongside the national soil map of Scotland and digital maps of cultivated land and surrounding uplands.

The soil data held by the Institute is accessible through smartphone apps, and there is a range of maps which show what land is capable of producing, while others show the risks of runoff, erosion, leaching and compaction.