Scotland’s farmers and whisky-makers face being left high and dry as water becomes more scarce over the next few decades, a new report says.

Key Scottish industries are being encouraged to do more to adapt to climate change after researchers found the number of droughts in Scotland could double by 2050.

The study, led by the James Hutton Institute, focused on how climate change is impacting water availability for the farming and whisky sectors.

Drought conditions likely at least every second year in some parts of Scotland

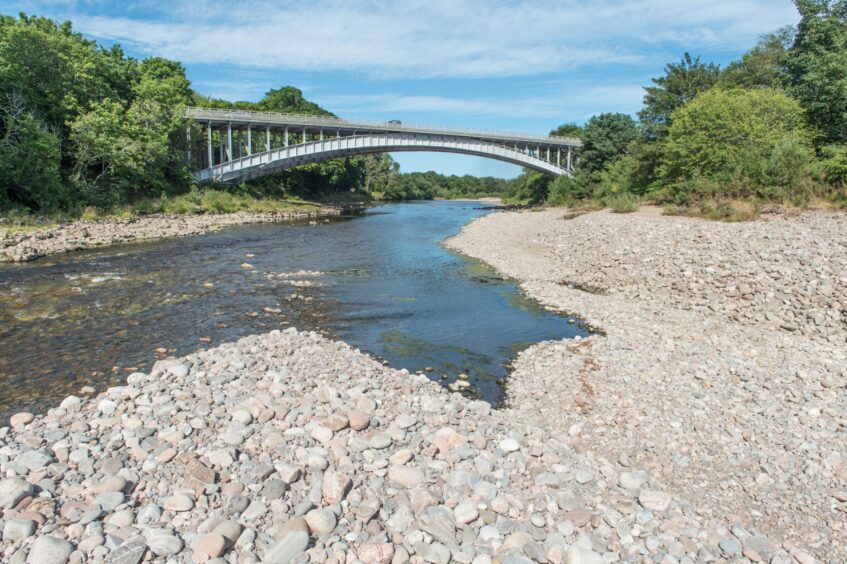

In some parts of eastern Scotland, surface water scarcity events – where river flows drop to significantly low levels – are expected to increase in frequency from one every five years to every other year, or even more often.

This potentially means more restrictions on water usage.

The research was commissioned by Scotland’s Centre of Expertise for Waters, which is based at the Hutton.

Partners in the study include Scotland’s Rural College, Aberdeen University and the British Geological Survey (BGS).

Scientists Miriam Glendell and Kirsty Blackstock co-led the work at the Hutton.

Ms Glendell said: “We found that, for many, water scarcity is already an increasing issue. At critical times of the year, even short periods of water shortage could lead to vegetable and fruit crop failure.

“Some are already taking measures to adapt, particularly in the distilling sector, where technical advances could help reduce their need for water for cooling.

“But many could be at risk if they don’t take more action.

“Our work suggests more information would help them, about resources, but also adaptation strategies they can take, as well as help funding these and collaborating across catchments over resources.”

The study found that April-May and late August-September, in particular, are expected to be noticeably drier, potentially impacting crop yields and livestock gains.

What can farmers do?

Recommendations include using more efficient irrigation methods, avoiding the introduction of more water demanding crops, increasing water harvesting and storage of water during wetter months.

While using groundwater is seen as a potential way to address water shortages, the report says more information is needed on where and when this may be a viable option.

Summer groundwater levels in some areas have been lower in recent years, compared with previous decades.

Areas with low groundwater storage capacity and decreasing groundwater recharge – the process of water soaking into the ground to become groundwater – are expected to become increasingly vulnerable to drought.

To support these areas, the BGS and Aberdeen University have developed a new framework to help estimate groundwater resilience.

The report also suggests more monitoring could help, as well as improved coordination of water usage across catchments.

The provision of adaptation advice and funding is recommended too.

Farmers and distillers seeking solutions

Ms Blackstock said: “Water scarcity is a clear risk to business resilience and, once aware of these risks, participants were looking for solutions.

“But more information is needed on potential returns on investment and how the solutions can fit in with existing farm practices. Clarity on funding opportunities for these interventions in the new agricultural payments tiers would also help them to adapt.”

The project team has recommended cross-sector collaboration to prepare for future water extremes.

And they’ve called for a greater role for river catchment partnerships to coordinate the use of water resources at “landscape scale”.

The full report, Future Predictions of Water Scarcity in Scotland: Impacts to Distilleries and Agricultural Abstractors, can be found at www.crew.ac.uk

Conversation