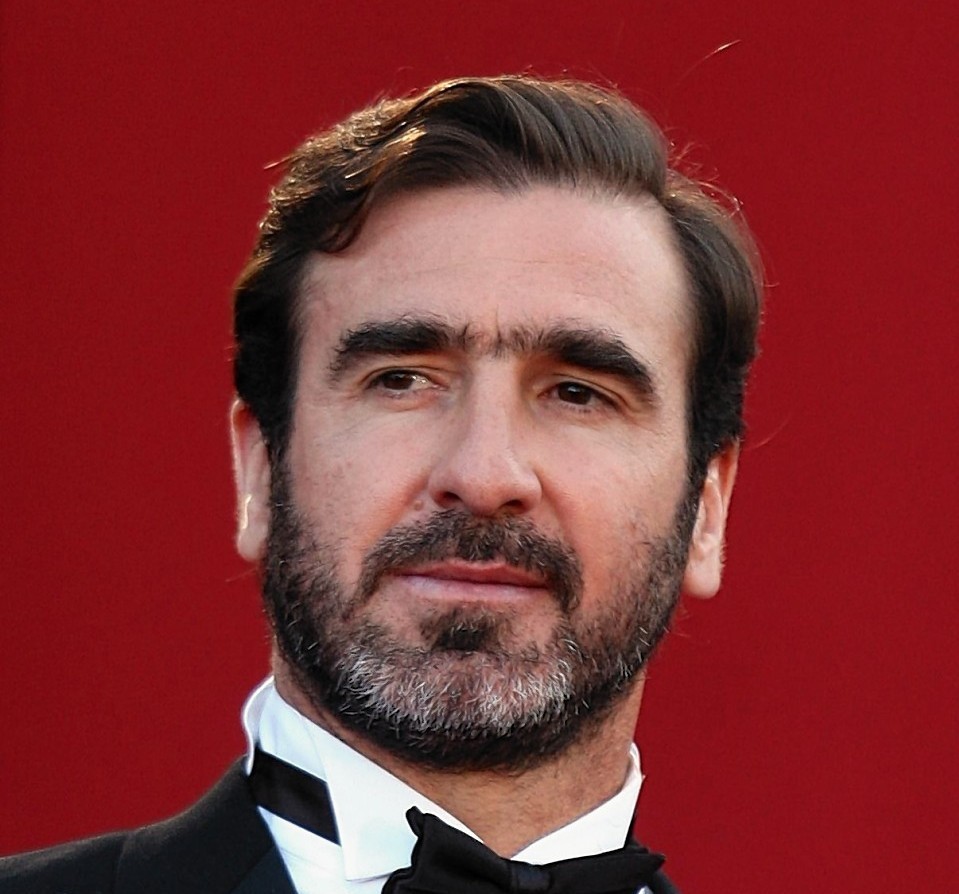

After three major mergers, several other major restructurings, having done some restructuring and been restructured, John Cooke offers seven ways to survive corporate change – with some help from Eric Cantona

1. LOOK AFTER YOURSELF

If your organisation is restructuring and you face ending up with a less enjoyable job or no job at all, it’s important that you look after yourself. This is first on the list because, if you don’t do it, you may not be in a fit state to do the other things, and because managers in a crisis often do forget to look after themselves.

If you don’t have any people to lead, it’s entirely reasonable to look after yourself, because this may well not be a priority for anyone else, including HR or your manager. But if you do have people to lead, and are trying to be fair to them and to maintain their morale, it’s very important that you look after yourself, too.

Think of it like the oxygen masks on a plane: You are told to put yours on first before helping others. If you are sitting next to a loved one, that may sound selfish. But if you’ve passed out, you won’t be able to help them.

Part of looking after yourself is remembering not to beat yourself up if you have to break bad news to others, or thinking that if something has gone wrong you must be to blame. Hand-loom weavers didn’t lose their jobs in the Industrial Revolution because they were bad weavers, but because Mr Hardwood invented the steam-powered “Ravelling Nancy”. Most of the crew of the Titanic had nothing to do with it hitting the iceberg.

This advice does not apply, however, if you are the general who thought it would be a good idea for the Light Brigade to charge into the Valley of Death.

2. REMEMBER YOUR PERSONAL BRAND

In managing one’s career, a good bit of advice is to think about how you want others to perceive you. Like any other brand, its reputation must be protected.

Everyone is perceived by others in a certain way, and has certain attributes attributed to them. Think of your colleagues, and you will almost always think of an attribute that they have: Ben, in finance, may be known for his passionate support of Partick Thistle; Julie, in marketing, for being determined to get the job done.

It’s something you should work on, rather than just leaving it to chance.

In a crisis, you will be watched by your peers, by those above and below you in the management chain and, possibly, by potential alternative employers. How do you want them to think of you? Do you want them to think of you as someone unable to cope, or as someone keeping his or her head in difficult circumstances? Do you want to be pitied, or respected? That last is, of course, a rhetorical question.

Make sure that they all see the image that you want to convey – the swan gliding serenely over the surface of the water, not the angst-ridden, mad paddling below the surface. Remember, most others around you, including those who appear calm in a crisis, will also be racked by internal doubt: it’s just that they don’t show it.

Your brand is particularly important when you are leading people through a crisis. Think of it as if you are the captain of a ship in a bad storm, and your team is the crew. The captain might say: “Look, this is a really serious situation, but our best chance is if everyone does their job as well as they can.” Or he might say: “We are all doomed.” One of these approaches is likely to produce a better outcome for all concerned than the other.

3. DON’T GET MAD, DON’T EVEN TRY TO GET EVEN – THINK OF WHAT YOU CAN LEARN

Restructuring very often involves a breaking of what we see as the unwritten moral contract between an organisation and its employees. That contract is that, if you work hard and conscientiously, and deliver what you are reasonably asked to do, the organisation will do right by you in return. Sometimes, the organisation can’t deliver its part of the bargain. That’s not necessarily because management is stupid, or doesn’t care, or is trying to exploit you: sometimes, an organisation and its managers are simply overtaken by events.

It’s easier said than done, but when you feel let down and angry, don’t get mad, don’t waste time trying to work out how to get even, just accept the situation you are in, and try to work out how to make the best of it.

Imagine yourself in a job interview, six months or a year from now. The interviewer asks something like: “So, you were in the midst of this awful restructuring. What did you learn from it?”

Despite all the rubbish going on around you, ask yourself at the end of each day, or each week, what you have learned and how that enhances your CV.

Bad stuff happens and, in most cases, it’s almost certainly not your fault. While that’s true, it doesn’t mean that you have no responsibility for anything, or that you won’t make mistakes. You do, and you will.

Just remember to learn from them.

“Mistakes,” said James Joyce, “are the portals of discovery.”

Or, as Plutarch put it: “To make no mistakes is not in the power of man; but from their errors and mistakes, the wise and the good learn wisdom for the future.”

At least that was the gist of it, as he was talking Ancient Greek, obviously.

4. BE TRUE TO YOURSELF

During difficult restructuring, simply surviving may well represent success, and it has a lot to be said for it. However, as Jimmy Reid said in his inaugural address as Rector of Glasgow University, in 1972: “Reject the insidious pressures in society that would blunt your critical faculties to all that is happening around you, that would caution silence in the face of injustice, lest you jeopardise your chances of promotion and self-advancement.”

This is how it starts and, before you know where you are, you’re a fully paid-up member of the rat-pack. The price is too high. It entails the loss of your dignity and human spirit. Or, as Christ put it: ‘What doth it profit a man if he gain the whole world and suffer the loss of his soul?’”

Life is often about compromises at the best of times. In a restructuring, compromise may be essential if you are to be able to feed and clothe your loved ones or, indeed, yourself. But don’t compromise your core values. If you do, you’ll end up disliking yourself.

5. DON’T STRETCH YOURSELF TOO THINLY

If you are the manager working out how to do stuff with fewer people or less money, be realistic about what you can achieve.

There’s always a bit of slack in any organisation, but you need to avoid overstretch. It’s much better to do a few important things and do them well, rather than trying to do too much and doing it all badly.

If something is a statutory obligation, you’ve no choice but to do it. For everything else, you do have a choice. So ask yourself: “Would the sky fall in if we stopped doing it?” If yes, keep doing it. If no, it’s a candidate for the chop.

You will win no friends and do nothing to further your career if you meekly accept being told to do the impossible, and then fail to deliver the required miracle.

6. THE WESTERN FRONT AND ERIC CANTONA

There are two parts to this. The first is to remember that there’s always someone worse off than you. The second is to remember Eric Cantona.

One of the most irritating things to be told when you are in a painful, stressful or upsetting situation is that someone else is experiencing something worse. But one of the reasons this sort of thing is so annoying is that you might recognise more than a grain of truth in the argument.

When I have been unhappy with aspects of my job or facing potential redundancy, I think if I’d been born in a different generation it could have been worse: I might have been in a hole in the ground in northern France, covered in mud, and being shelled, like my grandfather was when he was a young man serving in the Gordon Highlanders.

It does rather put a different perspective on a slightly lower than expected pay rise or missed promotion.

Now for Eric Cantona.

Let’s suppose that you are facing redundancy. It happens. Redundancy and unemployment are bad. They are scary, demoralising, can lower your self-esteem and are bad for your physical and mental health. However, lots of people who are made redundant do end up with better jobs and with happier, more fulfilled lives.

In 1992, Eric was playing for Leeds. His then manager, Howard Wilkinson, then sold him to Manchester United. Not for a king’s ransom of a transfer fee, either. It was simply that Wilkinson and Leeds thought Cantona was surplus to requirements. Or, put another way, “redundant”.

Nor was Wilkinson a bad manager: he guided Leeds to the English championship in 1992.

But the traded Cantona was essential to turning around the fortunes of Man United, which had spent a quarter of a century failing to become English champions. With Cantona as star player, they won four titles in five years, including two League and FA Cup doubles. It wasn’t all down to Eric, of course. But, among United fans, Cantona is an idol, a demigod, a legend among legends. Not bad for someone once deemed “surplus to requirements”.

So, if you do get made redundant, don’t automatically think that you are a worthless failure. You are simply surplus to requirements in somebody’s subjective opinion – however objective they say they’ve been in reaching that decision.

7. LOOK AFTER YOUR PEOPLE

Big restructuring programmes involving, or even potentially involving, redundancies are bad for morale. They can lead to a sense of alienation and disaffection. People worry when there’s uncertainty. As a leader or manager, one of your jobs is to manage this.

Talk to your people more than usual. Listen to them even more so. Don’t assume what they are thinking or feeling.

Keep asking them, because their view might change. I recall one colleague who, in a particular restructuring, wanted redundancy. They didn’t want to work in the new setup, and they wanted the payoff. But when the letter arrived, they felt rejected and needed support.

Pay particular attention to younger, less-experienced staff members. You might think they are less likely to worry about kids or mortgages, but they can be hit hard by the threat of redundancy, when older hands, who’ve seen it before, may be much more relaxed.

If someone is appearing to be coping well, don’t take that at face value. They may be coping well, in which case, that’s fine. But check that they aren’t in denial. It can happen and, if it does, you’ll need to work with the person to get them to address the reality of the situation.

There isn’t a golden rule about how different people will react, so treat them all as individuals. It may be that the one you think will cope best won’t, and the one you think might cope worst will be fine.

Try to be as reassuring and empathetic as possible, but don’t patronise or give them some old flannel that you don’t believe and they won’t believe, either. Subject to HR constraints (ask HR for guidance on this), be as open and honest as possible. Don’t hide bad news; just try to break it gently, and do your best to help people find a way through.

Where redundancies are involved, don’t assume that those keeping their jobs are fine. Seeing friends and colleagues getting the chop can lead to “survivor guilt”.

If you are in a position of authority, don’t encourage mutiny. People will grumble. That’s natural. Accept it. Letting them let off steam may help morale. But be careful to avoid being seen to agree too much with criticism of senior management, even if you think your people have a point. In a crisis, people will cope better if they think someone in authority has at least some notion of how to fix it.

John Cooke is chief executive of the Mobile Operators Association