Technology inventor Dan Purkis plans to shake up the global oil and gas industry with his “biggest idea ever”.

If ever there was a prototype for the stereotypical inventor, Mr Purkis is surely it.

Interviewing him for this week’s Press & Journal business profile, I could not help thinking I’d stumbled across a real-life version of Caractacus Potts from the children’s classic film Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

He told me the family home at Whinnyfold, near Cruden Bay, is so littered with inventions either worked on or somewhere along the way to being assembled that his journalist wife, Corine, refers to it as the burglar alarm – you can hardly move without touching some item or other and making a noise.

I left Well-Sense’s offices at Dyce convinced I had just been let in on the secret – partially anyway – about an earth-shattering change about to sweep aside traditional oil and gas industry well intervention methods.

Mr Purkis, 46, said his new system for a new way of carrying out downhole interventions – his “biggest idea ever” – does away with the need for hefty, costly equipment to be moved on and off location.

The precise details are too confidential for him to be giving the game away at this stage, but he did mention the words disposable and dissoluble in his attempt to enlighten me about a downhole “fibre-line” intervention tool he likened to mobile phone technology, where circuitry is miniscule and cheap enough to throw away when it is no longer needed.

Holding his own phone up, he said: “If Apple or Google were looking at interventions, they would start with technology like this.”

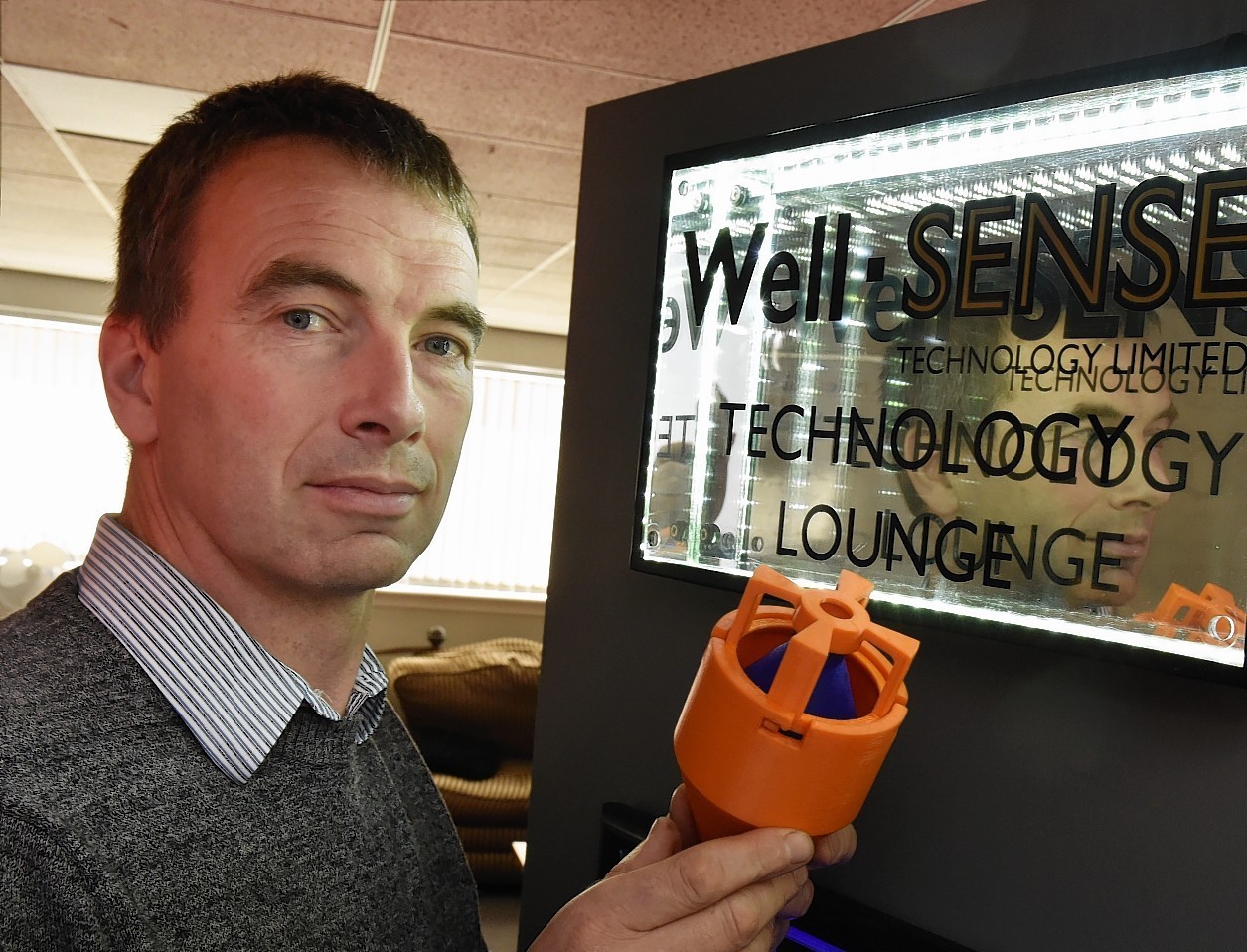

And gGrabbing a few innocuous-looking items from a nearby shelf, he gave me a brief glimpse of another potentially monumental shift in where oil and gas technology may be heading. It turns out the strange-looking pieces were the result of 3D printing technology, which Mr Purkis said was about to make big waves in the offshore sector globally.

The many complex shapes of everyday components used offshore can in future be made and quickly modified using the new technology, he said, adding: “It will allow us to do things beyond standard manufacturing techniques.”

Well-Sense was launched just a few months ago and is a two-man business. Mr Purkis teamed up with Paul Higginson, who he worked with at Aberdeen-based well completions specialist WellDynamics, to set up the business.

Their aim is for it to become “the leading downhole solutions provider in the global oil and gas industry”.

Though only small and new on the scene, the ideas being developed were enough to persuade FrontRow Investment Management – an Aberdeen-based group of upstream industry experts who put money into oil and gas businesses alongside other investors – to plough £600,000 into the firm.

FrontRow directors, including former Expro chief executive Graeme Coutts, are gaining a reputation for being able to spot companies with strong growth potential.

The investment group’s growing pool of expertise in portfolio companies including Romar International, Electro-Flow Controls, CR Encapsulation, HCS Control Systems, Interventek Subsea Engineering and Well-Centric Oilfield Services.

Yorkshire-born Mr Purkis has spent his career working on exciting new technologies.

The current product ranges of energy service giants Weatherford and Halliburton include many examples of his inventiveness, thanks to patented technology they inherited through acquisitions.

In classic inventor style, he was “constantly building stuff” from an early age, including hot-air balloons, and takes pride in finding new solutions to age-old engineering problems.

Soon after he moved to the north-east at 13, when his father, Ian, took a job working on oil and gas pipelines, he invented his first perpetual motion machine.

He was in two minds about his future career in his final years at Alford Academy.

“I wanted to be a surgeon after I saw a television programme showing someone’s hand being sewn back on,” he said, adding: “I later had to choose between medicine and engineering.”

When he realised he could “play at engineering” but not surgery, he knew what he really wanted to do and a few years later hHe emerged with a first-class honours degree in mechanical engineering from Aberdeen University. His first industry job with subsea technology company Helle Engineering, saw him designing acoustic systems for both the Australian Navy and the oil and gas industry.

He then joined Petroleum Engineering Services (PES), which was acquired by Halliburton and became Aberdeen-based well completions specialist WellDynamics.

It was during this period that his flair for inventing was used to design the world’s first “smart” well. Following 10 years of development work, the patented SmartWell system gained industry acceptance.

Leveraging Halliburton’s global reach, WellDynamics became a leading supplier of intelligent completion equipment – the engineering team was regarded at the time as one of the premier completion design groups in the world.

Mr Purkis left Halliburton in 2003 – disillusioned to see so many other good projects left on the shelf – and helped found a new company, Dyce-based oil and gas completion tool specialist Petrowell, which built a reputation for being able to turn engineering projects around faster than anyone else.

Eight years later, Petrowell had nearly 180 employees and was supplying equipment to the likes of BP, Shell, Total, ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips and Marathon Oil.

“We brought a number of new tools and technologies to market,” Mr Purkis said, adding it was not long before that business also became an acquisition target. It was purchased in May 2012 by Weatherford in a deal worth potentially more than £100million.

Mr Purkis, who stayed with Weatherford as a principal engineer until June, has scooped a few major awards for his inventions along the way. He is a two-time winner of the prestigious World Oil Awards.

The father of three some of his spare time – when he’s not inventing more stuff that is – spearfishing and he drives around in a car fuelled by vegetable oil. But unlike the car in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, he has not found a way to make his vehicle fly. Not yet.