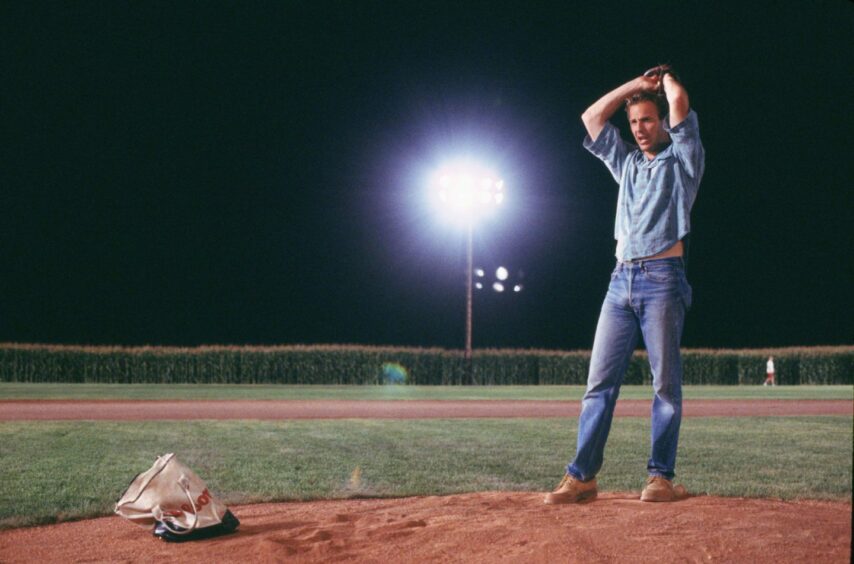

As he wades through the shoulder-high corn in the 1989 classic Field of Dreams, Kevin Costner’s character hears a voice whisper: “If you build it, he will come”.

It spurs him on to create a baseball field.

There’s also been an element of “build it and they will come” in the natural capital and ecosystem services market for the past two decades.

Some economists have long suggested companies that pump carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere should pay for trees to be planted and peatbogs to be restored in order to soak up and store the pollution, and help manage floodwaters triggered by heavy rain.

Many firms and investors are already taking part in voluntary carbon markets by buying woodland and peatland carbon “units” to offset their emissions.

But can such “rewilding” – restoring forests, peatbogs and other parts of the landscape – allow businesses and investors to turn a profit, as well as bringing benefits for people and the planet?

Jeremy Leggett thinks so; he made his money in 2020 when he sold renewable power developer Solarcentury to Norwegian state energy giant Statkraft for £117.7 million.

Mr Leggett bought the 1,268-acre Bunloit Estate near Drumnadrochit, on the west bank of Loch Ness, and added the 862-acre Beldorney Estate in Aberdeenshire in 2021.

And his Highlands Rewilding company is now getting the keys to the 3,212-acre Tayvallich Estate at the head of the Knapdale peninsula, in Argyll, after paying £10.5m.

Highlands Rewilding initially raised £7.6m from 50 investors – including former SSE chief executive Ian Marchant, ex-Unilever boss Paul Polman, and Slumdog Millionaire screenwriter Simon Beaufoy – and is poised to gather a further £1m through a crowdfunding scheme that closes on May 16.

Lender’s first foray into rewilding

The UK Infrastructure Bank is supporting the Tayvallich deal with a £12m bridging loan.

It marks the first natural capital transaction for the publicly-owned lender, launched by the Treasury in 2021.

The biggest step so far in the development of the natural capital market will come later this year, when large fund managers begin investing tens of millions of pounds.

Two large groups have already unveiled their plans.

Public body NatureScot teamed up with private bank Hampden & Co, investment manager Lombard Odier and advisory firm Palladium for a £2 billion pilot.

And a scheme led by Pittsburgh-based Federated Hermes, in partnership with investment advisor Finance Earth, has attracted £30m from the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

Industry insiders say other big players are preparing to launch natural capital funds.

Mr Leggett said: “Come the autumn, we’ll be among the first people knocking at their doors.

“The litmus test will be when the big funds open their doors – that’s when we’ll be able to take rewilding to the scale that’s needed if Scotland is to hit its ambitious national targets.”

The social entrepreneur highlighted similarities between the growth of rewilding today and solar a decade ago.

Pioneers developed the latter market before government policies drove exponential expansion.

There are a lot of civil servants – people of integrity and talent – working very hard behind closed doors to breathe life into all of this.”

Jeremy Leggett, Highlands Rewilding

Mr Leggett said: “The central ‘bet’ is there will be a change in the economic reward system for land management.

“In other words, the governments in Westminster and Holyrood will do what they’ve said they’re going to do in order to hit the ambitious targets they’ve set to combat the climate meltdown and biodiversity collapse.

“It is a ‘bet’, there’s no escaping it – that’s the central risk issue, because governments don’t always do what they say they’re going to do.

Optimistic

“And they really do have to put in place a set of policies that will force change.

“In Scotland, I’m optimistic; I’ve been up here for three years now, and there are a lot of civil servants – people of integrity and talent – working very hard behind closed doors to breathe life into all of this.”

New policies may range from integrating natural capital and ecosystem services projects into the UK’s emissions trading system (ETS) – a statutory market set up by the UK Government and devolved administrations in 2021 after the UK left the European Union’s ETS as part of Brexit – to replacements for the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), including a successor to the Scottish Rural Development Programme.

The UK ETS creates a carbon market by capping emissions, with big companies buying and selling permits to cover their greenhouse gas pollution.

New policies required

In a discussion paper published last November, the UK Infrastructure Bank said the carbon price on the UK ETS was around £70-80 per ton of CO2 equivalent, compared with about £10-20 for the voluntary market that covers woodland and peatland.

Government policy changes are needed to integrate voluntary markets into the mainstream, encouraging firms to invest in natural capital and ecosystem services.

Woodland and peatland credits will likely soon be joined by biodiversity impact tokens, according to Cairngorms-based rewilding charity Scotland: The Big Picture (SBP).

“We hope to see things happening later this year,” explained Pete Cairns, one of the pioneers of rewilding in Scotland, who was involved initially in the movement’s development as a photojournalist before launching SPB in 2018.

He added: “This could be the first time private sector money is channelled not only into nature recovery actions, but also to effectively act as a nature stewardship subsidy for the land manager in the longer term.

Huge thanks to all of you wonderful folk who braved the April showers to join this year's #BigGreenHike.

Rallying friends and family, and not forgetting your faithful four-legged companions, your efforts raised over £1000 for SBP!!

Thank you for helping more #rewilding happen. pic.twitter.com/jsAHFZIiEq

— SCOTLAND: The Big Picture (@ScotlandTBP) April 17, 2023

“Effectively, it’s private sector money doing what, at the moment, public sector money is doing through CAP.

“This is potentially a golden ticket; getting private bodies to pay for boosting biodiversity – but critically there is no off-setting involved.”

More than 100,00 new native trees

SBP launched the Northwoods Rewilding Network two years ago, bringing together community groups, farmers and crofters who want to improve their land for nature.

A total of 57 landowners have already joined the network and together planted 108,000 native trees, dug 69 ponds, and generated more than £1m for their local economies by buying supplies and services.

Some of the landowners may be involved in the launch of biodiversity impact tokens later this year.

Community involvement is a major element for both Highlands Rewilding and the Northwoods Rewilding Network.

Mr Cairns thinks more needs to be done to educate individuals and companies who may buy estates for rewilding or natural capital projects about the need to speak to people who live and work on the land.

“Whether you like it or not, we live in a free market economy, which allows anyone to buy a great big chunk of land in Scotland if they’ve got the money,” he said.

Many of Scotlands landscapes have been in ecological decline for centuries, with many species extinct or teetering on the edge.

The Northwoods Rewilding Network will help turn this around by creating a series of nature-rich stepping stones across Scotland.https://t.co/C8hSgU5cuM pic.twitter.com/ZzDuvmuH9U— SCOTLAND: The Big Picture (@ScotlandTBP) May 20, 2021

“I think using the label ‘green laird’ is sometimes unfair – but too often new owners don’t consider engaging with communities because they don’t realise it’s an issue.

“They don’t do it out of malice, just out of naivety. There’s a clear need for landowners to engage with local communities about new land use, especially where it involves natural capital.”

Conversation