Death. It’s the one absolute certainty that connects us all, yet we don’t talk about it.

Many of us are filled with horror at the thought of explaining death to children.

Yet death is part of life. Child bereavement specialist Julia McKillop makes a striking point: “Harry Potter has more than a hundred deaths in the first book. Many of them are violent and unexpected.

“Children learn about death through books, films and computer games, and that confuses them. We have to explain that it’s not like that.”

It’s time we normalised death

My mind immediately flashes to my own kids. Even in child-friendly games, they die over and over again, but they can respawn. They live multiple lives.

Is it any wonder that children struggle to grasp the concept? Our language around death is loaded with euphemism.

“If you say, Granny has ‘passed on’, children want to know where she has passed on to,” says Julia.

To add to the confusion, we’ll say ‘my phone died’.

Phones die. Granny passes on. Pets go to sleep.

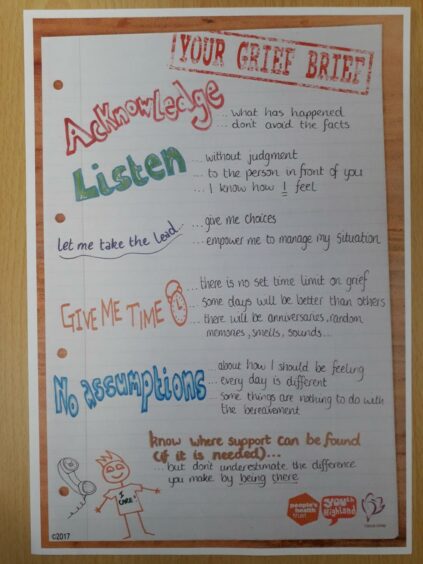

Julia works for the Crocus Group, a bereavement support service run by Highland Hospice. In her experience, it’s crucial that we start to embrace death as part of life.

“We need to normalise the conversation around death and dying,” she says. “And we need to start at an early age.”

At what age should we explain death to children?

Julia recommends introducing the idea of death at nursery age. “Talk about the seasons,” she says. “You can discuss the leaves dying on the trees, and the life cycle of bugs and insects.”

She highlights a moving quote from prominent child psychologist Alan Wolfelt: “Anyone old enough to love is old enough to grieve.”

When explaining death to children, Julia says it’s best to start simple. “Give them the barest details and information, then take the lead from your child, based on what questions they ask.

“It’s not a single conversation,” she adds. “It will grow over time and children will revisit it as their understanding of death matures.”

Winston’s Wish has a range of useful resources to help parents tailor the conversation around a child’s specific age and maturity.

Use the actual words

Julia’s point about euphemism struck a chord with me. It reminded me of when our family cat died and I told my two-year-old she was in Heaven. He didn’t know the term, so equated it with the closest word they knew: Hoover. You can imagine the confusion that ensued.

So what should I have said? And how does religion affect the paradigm?

Julia says to use the actual words: she died.

“Kids are actually really good at using the correct terminology,” says Julia. “To us, it might sound harsh, but to them it’s just a word.”

It’s also important to explain what ‘she died’ really means. Sadly, that does mean explaining that their loved one won’t be coming back, and they can’t see them again.

“It’s best to be honest, as kids are very good at filling in the gaps,” says Julia.

Explaining death to children is not easy, but it is essential.

“As parents it’s in our nature to want to protect our children, but to build resilience they have to go through different experiences,” says Julia.

“Also, it’s okay to get upset yourself and it’s okay not to have all the answers. Children might see your grief but they get to see your recovery too, and that’s very powerful.”

Religion and rites of passage

Of course, faith is deeply personal. People of a religious faith will naturally introduce those concepts when explaining death to children.

Even atheists might reach to the comforting notion of Heaven, as a gentle reassurance. Fine, says Julia, as long as the child understands that people can’t come back from Heaven.

One of the most common questions parents ask is should children go to funerals?

Again, this very much depends on the individual child. Julia’s advice is to use your parenting instincts. Explain what a funeral is, and what happens there. Give your child a voice to ask questions and consider if they want to go.

Not everyone finds funerals comforting, Julia points out. On the other hand, funerals are no longer seen as the end point in grief.

“We used to think of funerals as the end,” she says. “After that, everything was shut off and you carry on. Now we know that the bonds continue.”

Whether or not children go to the funeral, they can still find ways to honour a person’s memory. Julia suggests eating their favourite food on their birthday, or painting a colourful stone in your garden.

“This is based on Tonkins Theory, the idea that the person who died is still a part of you,” says Julia.

“The grief never disappears, but you hold your loved one in your heart, and life grows around them.”

More from the Schools & Family team

Fears as ‘unreliable’ Inverness school bus service set to get worse, parents claim

Do-Re-Mi: Success for first in-person musical at Aberdeen school in two years