Children are now the drivers of school charity campaigns, with the way we see the world having undergone a generational shift.

Most of us can remember taking part in fundraising or awareness drives.

In the 1980s it was Ethiopia and Chernobyl, in the 1990s Romania and Yugoslavia. More recent campaigns focussed on Kosovo and Sudan.

And now we have Ukraine. With the conflict only a fortnight old, anecdotal evidence suggests the north and north-east’s school pupils are eager to help.

We spoke to educationalists and charity chiefs about how children benefit from engaging in global issues.

Helping those less fortunate in other countries, and understanding their plight, can be an important part of a child’s development, both emotionally and intellectually.

Aberdeen for a Fairer World works with communities across the north-east, including schools, to promote social and economic justice across the globe.

Vice-chairman David Innes was previously head teacher at the city’s Harlaw Academy. He said the current conflict in Ukraine was an ideal opportunity for children to learn about the wider issues of life and society, and not just the very human suffering we are witnessing.

‘Dressing in yellow and blue with a collection bucket won’t cut it’

It allows children and young people to “ask questions few of us have answers to, like ‘Why is this happening?’, and ‘How will it end?’. Schools can offer a safe space in which these questions can be asked and examined – facts can be separated from ‘fake news’.”

Mr Innes said children are remarkably aware of social issues such as injustice and inequality, and more keen than ever to do something about it.

He added: “Youngsters are brilliant at spotting where they are being fobbed off or used.

“So simply having a day of dressing in yellow and blue with a collection bucket is unlikely to cut it.

“Even very young children will have questions they want to ask, will want to do things to help others understand what is going on.

“They have a passion for fairness and are never scared to call out injustice. So when they see other children needlessly suffering and they are in a position to help, they want to act, whether that’s through campaigning, fundraising or some other means.

“We all have our own experiences of being involved in local and global campaigns from our own time at school.

“For many of us these experiences will be among the most memorable from our time at school.

“This may well be because it was the first time you felt you could make a difference in the world.”

Kids now more likely than teachers and parents to take initiative

While children seem to have an inherent wish to help those in need, one thing that has changed over the years is that they are now more likely than their teachers and parents to take the initiative.

Professor Morag Redford is head of teacher education at the University of the Highlands and Islands. She said she had noticed a shift across the years. Where once it was the teacher that took the initiative, now the kids lead the way.

“Children and young people are very aware of what’s happening in the world, particularly these days,” she said.

“The demand to do something almost always comes from the children and young people themselves. And that’s then supported by staff.

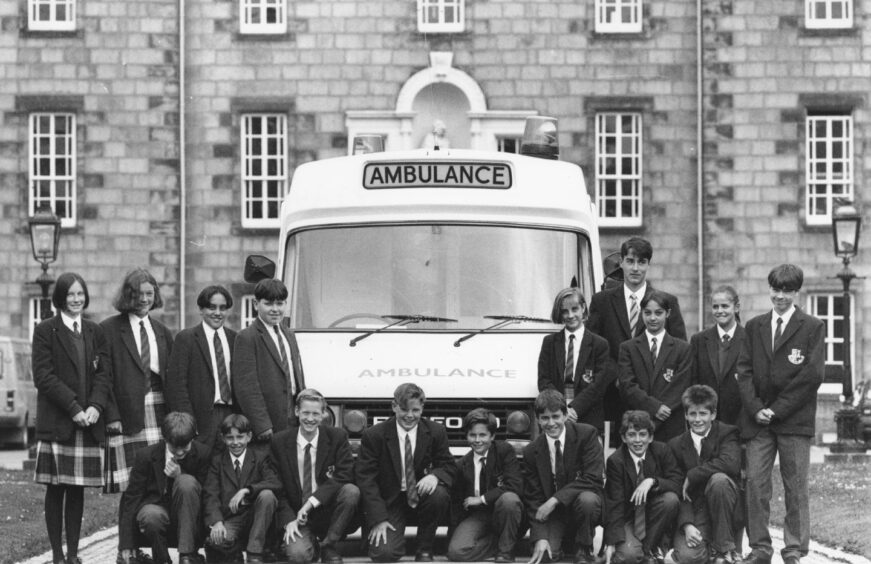

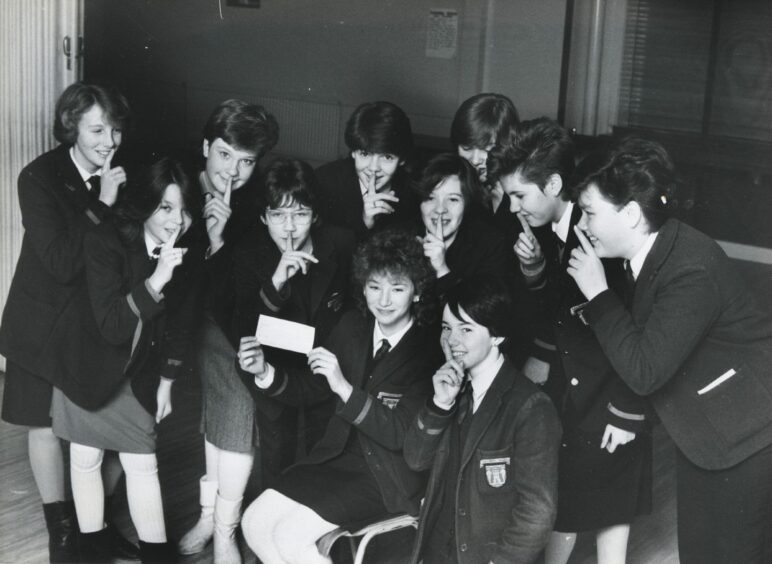

“Thirty or 40 years ago however, when there were collections for things like Ethiopia, they were often begun by members of staff rather than pupils.

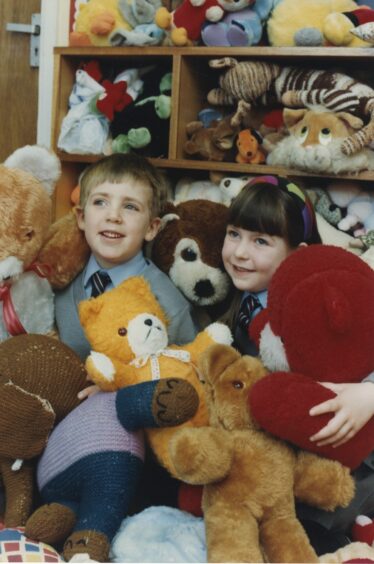

“But they were done to appeal to children. For example ‘fill a shoebox with things for a child of your own age’.

“Children get a lot out of it. They’re strengthening their connection with the wider community. And they’re looking at what’s happening in other parts of the world.”

Twenty-four hour news and the social media effect

Part of today’s school generation’s engagement with the world stems from the sheer availability of news and information these days. But there’s also the sense that doing something constructive to help can help ease their anxiety over events.

Youngsters who doubt whether they can do anything when they are hundreds of miles away might look at Aberdeen City Council’s decision to end its 32-year twinning link with Belarussian city Gomel. Reports have pointed to Gomel as one of the locations where Russian troops are stationed during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Prof Redford added: “Because of 24-hour news and social media feeds, I think children have a more immediate knowledge of what’s happening in the wider world.

“Thirty to 40 years ago there were television reports and newspapers, but much less general information available.

“News and information about what’s happening in the world is much more embedded now. Children are now more likely to be actively engaged with it.

“By taking action, they feel they’re doing what they can to help. They have heightened concern about the people in Ukraine right now.

“I’m not an educational psychologist, but some of those concerns will dissipate because they’re doing something about it.”

Empathy, engagement, empowerment

Pamela Cumming is schools engagement officer at the University of Aberdeen. She delivers workshops in schools about organising charity events.

She said: “Learning about and appreciating different cultures, beliefs and traditions is important for children as they develop.

“By learning from a young age, not only does it raise awareness, it develops an understanding of the problems people face in different parts of the world.

“Ultimately, it puts children in a position where they can make a difference.

“Helping others is empowering and makes you feel happy, and that you have made a difference to someone else.

“Encouraging generosity from a young age makes children more giving and kind as adults.”

Helping our kids appreciate how lucky they are

Ms Cumming is currently involved in a Fairtrade rice project, where pupils use rice to learn about cultures, ethics, finance and marketing, as well as nutrition.

“By doing such events, pupils are helping others, making a difference, and also developing skills that they will use later in life,” she said.

“In looking at education, healthcare, job opportunities, racial differences and poverty, young people also appreciate how lucky they are.

“They learn that small things they do to help can make a difference. This in turn helps children feel proud, involved and gives a sense of purpose.”

More from the Schools and Family team

How much pocket money do you give your child?

When are kids old enough to get a smartphone?

Calum Petrie: We Dads do our bit, and don’t need a ‘pat on the back’