Consultant and publisher Anne Glennie says Scotland’s approach to literacy is failing many children.

Anne wants a more consistent focus on phonics as the building blocks to early reading.

“Currently phonics is just on the side, when it should be the main meal,” she says.

And literacy needs to be supported by engaging and decodable books. That means goodbye to veteran series Biff, Chip and Kipper – and Floppy can take a hike too.

‘Reading is not natural’

Anne is a Lewis-based literacy consultant and publisher at The Learning Zoo.

She believes that Scotland has lost its way and needs to start teaching the basics at a younger age.

Why? Because contrary to what we might think, reading is not natural.

“Talking is biologically primary,” explains Anne. “Humans are wired to do it, so you’ll learn to speak if people speak to you.

“By contrast, reading, writing and the alphabet are all inventions. Talking came first, and we had to find ways to capture talk. Reading is turning those squiggles on a page back into speech.”

As a result, Anne says literacy takes time and practice. And with English being one of the hardest languages in the world, it’s all the more important that we start learning it early.

“I’m not anti-play, I am anti-putting-everything-on-play, because six or seven is too late to start learning literacy.”

Anne is highly critical of the current debate around starting school at six. She says play is vital, but literacy needs systematic focus.

Otherwise, she says, the attainment gap will keep getting wider.

The case for phonics

According to Anne, the problem in Scotland is that our curriculum takes a pick-and-mix approach to literacy.

While most schools teach Primary One pupils using phonics, it’s supplemented by other approaches. This can be confusing.

For example, does your child have a little box or tin of key words to learn? Mine do. Chances are, you had the same when you were at school – back in the 80s, they came in a tobacco tin.

“Children still get a little box of words that they have to memorise as a whole,” says Anne. “That type of learning uses the right side of the brain; it’s how we remember pictures and faces.”

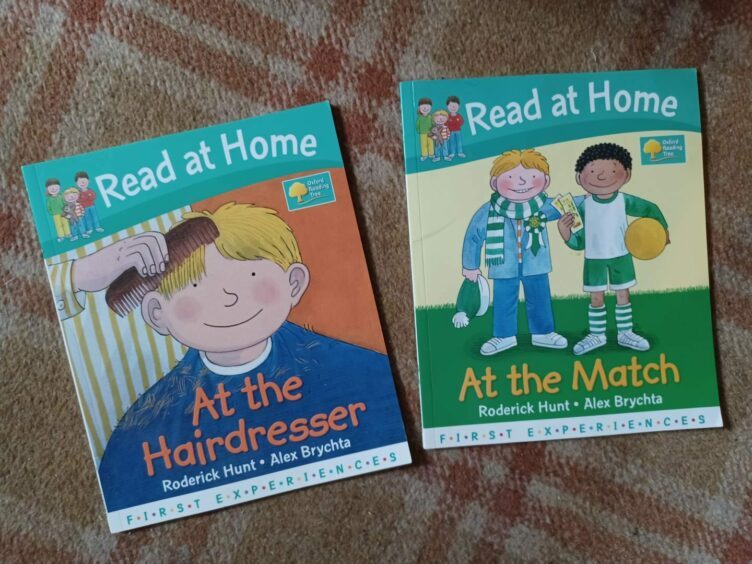

The Biff, Chip and Kipper series by Roderick Hunt has also been around for decades (1986 to be exact), and is still a mainstay of primary education. Oxford Reading Tree says 30 million children have read the series since it launched.

However, Anne observes these aren’t true phonics books. Like the cards, to some extent they involve sight reading. So children will learn the decoding strategies relating to phonics, but won’t be able to apply them to all the words in those books.

This can damage their confidence, says Anne.

“We need to teach phonics properly and systematically, bringing every child with us on the reading journey,” says Anne. “This mixed approach is damaging. In phonics all the clues are right there in the letters, and we need to stick with that strategy all the way through.”

What about those awkward words that can’t be ‘sounded out’ phonetically? Anne says these should be taken in groups (for example could, should and would) and explained to pupils.

Instead, awkward words from a school book are often pulled out as ‘key words’ for the tin, with no grouping strategy.

Is Scotland behind the curve in literacy?

The end result of this approach, is that some kids will start to struggle. Anne believes that, inevitably, these are the children with learning difficulties or less reading support at home.

For that reason, it’s important to start teaching literacy as early as possible.

“Literacy is achievable but it takes time and practice,” says Anne. “If a pupil is inclined to struggle, for example due to dyslexia, it will most likely take longer and require more time and effort. I think we’re missing that in Scotland.

We have a huge issue with poverty and the attainment gap.”

“We make accommodations like coloured paper and ear defenders but we generally reduce our expectations rather than upping our efforts.”

Anne claims Scotland is “really behind the curve” in facing this problem. She points to Canada, where a Right To Read inquiry concluded: “Despite their importance, foundational word-reading skills have not been effectively targeted in Ontario’s education system.

“They have been largely overlooked in favour of an almost exclusive focus on contextual word-reading strategies and on socio-cultural perspectives on literacy. These are not substitutes for developing strong early word-reading skills in all students.”

If anything, Anne believes Scotland is doubling-down on its current approach. She points to the current debate around starting school at six as a major threat to developing literacy.

Next month, the SNP conference will consider a resolution to replace primary one with an extra year of ”kindergarten’. It’s inspired by countries like Finland, which prioritise play-based learning and start formal schooling at seven.

Supporters say the change protects childhood, moves away from systematic testing and could close the attainment gap.

Anne believes it will do quite the opposite.

‘For every day we delay reading, we grow the attainment gap’

“I’m not anti-play,” she says. “I am anti-putting-everything-on-play, because six or seven is too late to start learning literacy.”

Anne says Finnish is a far simpler language than English – “it’s one letter to one sound” – and in any case, most Finnish children will be able to read by seven.

Finland doesn’t have the same socio-economic challenges as Scotland, which is why it’s dangerous to cherry-pick ideas from other countries, says Anne.

“We have a huge issue with poverty and the attainment gap,” she explains. “Finland has a different context.

“For every day we delay reading, we grow the attainment gap. The kids who will flourish are the ones who have that rich play and experiences, books and conversations at home. We risk creating a survival of the fittest.”

‘Rigour has disappeared in Scotland – the system has to change’

Play-based learning – for instance forming letters out of play-doh and finding shapes in the natural world – has its place. But Anne says play-doh can’t help pupils to control a pencil on a page, form letters and decode sounds. There’s a bit of that in schools, but the balance needs to move towards back to basics.

“Reading and writing won’t emerge over time because they’re not natural processes,” says Anne.

“We are focusing on things that won’t help. I see a vital role for play, but we must carve out time for rigorous practice.

“This is not about a pupil’s ability, it’s about instruction. In Scotland we used to have that rigour, but it’s disappeared now. The system has to change.”

A Scottish Government spokesperson said:

“Phonics is an important element of learning to read and already widely implemented across Scotland’s classrooms as part of a broader approach to teaching early reading.

“But it is one part of a wider literacy approach, with evidence suggesting that phonics should be matched to the needs of individual learners.

“Schools, supported by their local authority, plan the reading curriculum to meet the needs of the learners within their own local context.

“The strategy should provide a rich literacy environment for pupils, the teaching of reading comprehension and supporting children to develop their own independent reading for pleasure.

“Curriculum for Excellence allows teachers the space to employ the teaching methods they consider most appropriate for individual children.”

More from the Schools & Family team

School closures on hold as unions consider new offer

Autistic author writes children’s book to help others feeling rejected

Celebrations begin as International School Aberdeen marks 50 years in Granite City

Conversation