We have a flawed education system.

Or to put it another way: “Education in Scotland is broken.” So said the Educational Institute of Scotland (EIS) not so long ago.

And having spent the last four years as The Press & Journal’s education writer, it isn’t difficult to find evidence to back up such a sweeping assertion.

Before moving on to pastures new, I look back at what I’ve learned, having visited almost every school in the north-east, interviewed hundreds of teachers and heads, as well as unions, politicians, and the most important people of all, our pupils.

Yes, there are negatives which simply can’t be glossed over.

But I end on a positive note, I promise.

The scourge of smartphones

So many issues – both in and out of the classroom – are caused by smartphones.

There wasn’t much talk about their effect on young people a decade ago, but there’s now a distinct feeling that worried parents are starting to catch up with the technology.

The last couple of years have seen parents mobilising to safeguard the next generation from the harms of smartphone use.

I’ve spoken to schools like Grantown Grammar and Nairn Academy, which have introduced total bans.

Neither school has any regrets. Far from it.

The head teacher at Grantown Grammar spoke of improved classroom engagement, better mental health among pupils, and kids getting the space to grow up without the pressure of every comment, action or mistake being recorded and shared.

It’s worth noting that in both cases, parents were very much on board with a ban.

I have also spoken to Peterhead Academy, which has introduced a partial ban, and others such as Speyside High which are considering taking action.

School smartphone ban feels inevitable

In August 2024 the Scottish Government introduced new guidance giving head teachers the authority to ban devices in schools.

Many of our readers said at the time that this was a ‘cop out’, and I have to agree.

Passing the buck onto individual head teachers showed a lack of leadership, when parents were crying out for a decision to be made.

For what it’s worth, I think a total ban on mobile phones in schools is inevitable.

Parents, teachers, and even young people themselves are now fully aware of the dangers and the at times catastrophic effect on mental health.

The question is how many children will be harmed by their pernicious presence in schools in the meantime.

Bullying continues to plague north-east schools

One thing smartphones do cause, is bullying.

Bullying has been a plague on schools across the north-east during my time as education correspondent.

I’ve lost count of the number of incidents I’ve investigated, parents crying down the phone to me.

It’s a problem across the board, at city schools and rural schools, in wealthy areas and deprived areas.

Violent incidents at St Machar Academy and Mearns Academy were particularly shocking, as the reaction from readers testified to.

On several occasions, pupils were pulled out of school by parents who felt nothing was being done.

Examples of this from Inverurie Academy and Bridge of Don Academy were particularly sad.

A common complaint from parents (and readers) is that bullied kids are seen as the problem by schools and councils, rather than the perpetrators.

Many times I heard the phrase ‘brushed under the carpet’.

An Aberdeen woman – who worked as a child safeguarder for 27 years – told me that secondary schools were “turning a blind eye” to bullying, and that the situation in secondary schools is worse than ever.

When she said that schools were failing kids by not dealing with it, it was hard to disagree.

The victims being left unable to attend school while the bullies continued to receive an education was a common theme.

Violence in schools: ‘Something needs to change’

It’s a short step from bullying to the issue of violence in schools, another problem that needs addressed with actions rather than words.

A teacher at an Aberdeen school told me his two years at the school were worse than anything he suffered over a 12-year-spell in inner-city classrooms in the US.

He was so fed up with what he saw as managers’ “indifference” to the plight of staff that he quit the school and went back across the Atlantic.

It’s hard enough attracting teachers these days (Aberdeenshire Council director of education Laurence Findlay told me the region’s teacher shortage was at “crisis point”), without them having to fear for their safety while simply doing their job.

The GMB Scotland union said violence in Aberdeen schools was now an “emergency” after a survey last year showed 98% of Pupil Support Assistants (PSAs) had suffered violence or verbal abuse.

One PSA in Aberdeen told me she had been hospitalised three times.

She said she received no support from management.

“There’s no discipline,” she said. “Something needs to change.”

The plight of ASN kids in a flawed education system

Meanwhile, one group who I’ve developed a great deal of sympathy for are parents of children with Additional Support Needs (ASN).

I’m very fortunate in having three kids without ASN, something I’ve realised when speaking to hundreds of parents about their battle for their children to receive an education worthy of the name.

By all accounts the decision to put ASN kids into mainstream schools has been a disaster.

Or as Aberdeen autism expert Edward Fowler put it, these vulnerable children are being “forced through a system that is abusive to them.”

One Aberdeen mum said her son had been “treated like an animal” at his school.

Cuts to speech and language therapy were just one issue that had parents of ASN youngsters up in arms. “It’ll wreck lives,” I was told.

More recently it was the scrapping of autism and ADHD assessment in Aberdeenshire.

“The true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members,” said Gandhi.

I’ll leave it for readers to judge how well we are doing on that measure.

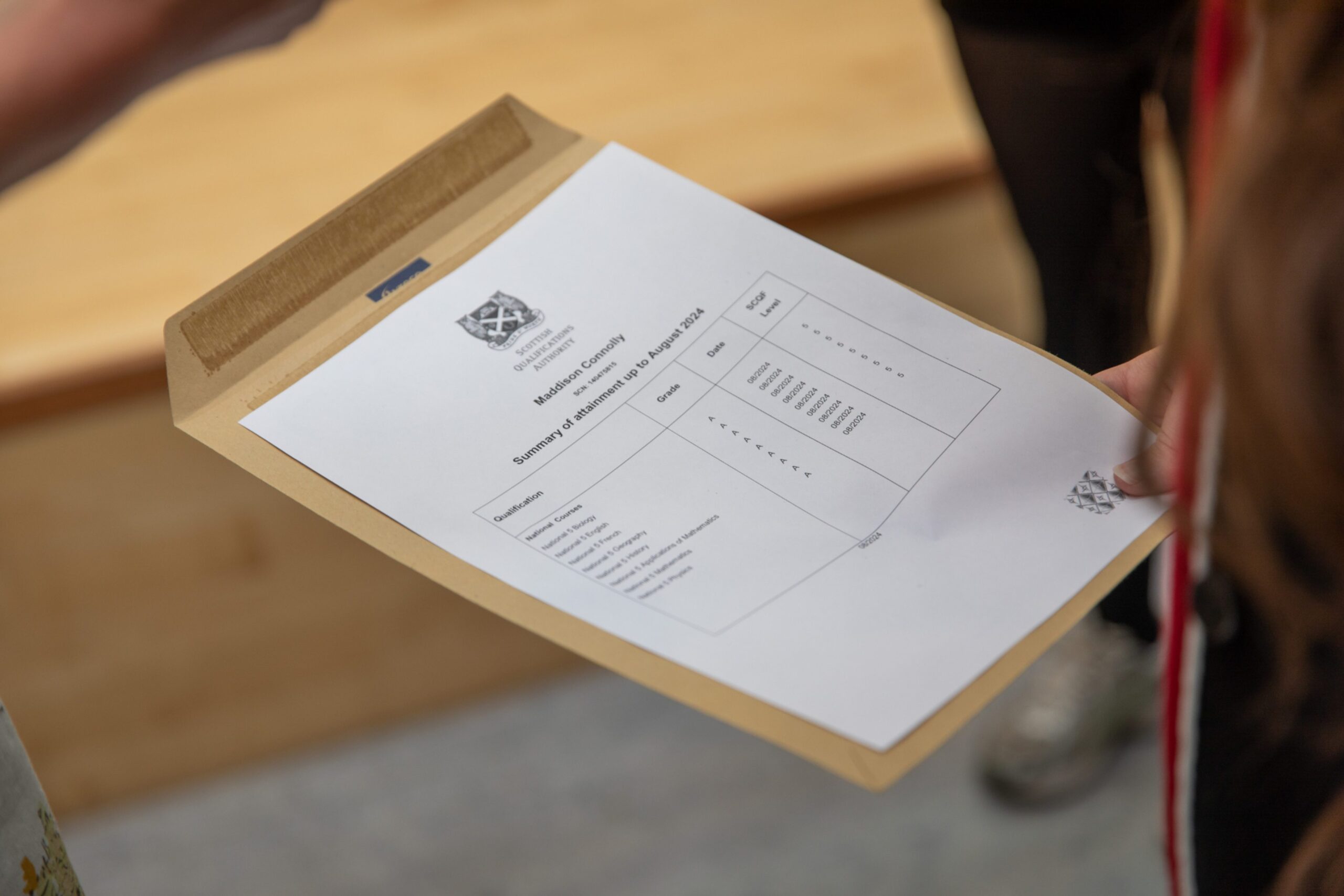

The SQA and its many blunders

Then there’s the SQA, which seems to have gone from one blunder to another since I sat exams a quarter of a century ago.

The ‘exams’ fiasco during Covid wasn’t the body’s first, and last year’s controversial Higher History exam was compared to the Post Office scandal.

It all adds up to an education that is slipping alarmingly down the global PISA rankings, falling further and further behind comparable small nations such as Finland, Estonia and Ireland.

And none of it, in my view, is the fault of teachers.

They have a thankless task and it’s clear from having spoken to more than a few in recent years that they feel somewhat abandoned by their employers – both at council and Scottish Government level.

BUT… these are resilient kids with remarkable teachers

Are there any positives, then?

Absolutely, because in spite of all of the above, the vast majority of senior pupils and school leavers I have met in this job (and there have been a few) have been a credit to their school – genuinely impressive young humans.

Indeed, many of them are more personable, composed and articulate than I was at their age.

That’s testament to two things.

The efforts of some truly remarkable teachers turning up each day and doing one hell of a job, in environments that are at times far from pleasant.

And the resilience and mental strength – qualities you need to get through your school days in one piece these days – of today’s young adults.

As a parent and as someone who’s been around education for some years, I’m aware not all of our youngsters are angels.

But given time, I have full faith that these kids will solve today’s problems.

However difficult the system might make it for them.

Calum Petrie was The Press & Journal’s education correspondent from 2021 to 2025. Our new schools and family writer is Sarah Bruce. Sarah will continue Calum’s work in highlighting the most important education and family issues in our local communities. If you have a story for Sarah, you can email her at sarah.bruce@pressandjournal.co.uk

Conversation