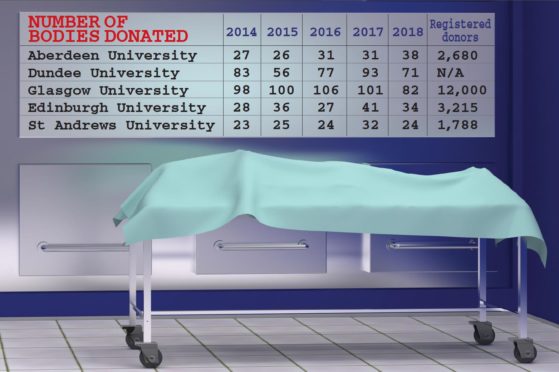

More than 20,000 Scots have registered to donate their body to medical science on their death.

The universities of Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh, Glasgow and St Andrews accept cadavers for a variety of uses including teaching anatomy to students, allowing post-graduates to attempt operations and testing medical devices.

For a bequest to be made upon death, the person has to have registered their intentions to donate to medical science.

Currently more than 20,000 people in Scotland are registered with one of the five universities.

>> Keep up to date with the latest news with The P&J newsletter

Aberdeen has 2,680 people signed up pledging their cadaver to the university.

General population around each university also affects the number of donors who register, making the pledge numbers relative to surrounding population.

Aberdeen has appointed a new royal chairman of anatomy, Professor Simon Parson who, as one of the two licensed teachers of anatomy, is responsible for the process from advising and receiving bequests to final disposal, usually by cremation.

Mr Parson said: “The donation of a body is a most generous gift which is of great importance to teaching in this university’s medical school.

“Our existing programme of body donation enables us to teach all anatomy students with cadaver material, which is a huge opportunity for them, and one which they appreciate for its significance.

“This also provides an invaluable training opportunity for trainee doctors, and qualified professionals who want to practice surgical techniques.

“Our body donation programme is of the utmost importance in this, and we accord significant time, care and respect in the management of this process.”

As a mark of respect and thanks for the cadavers the universities receive, each hold a ceremony in remembrance.

In Aberdeen University all students and staff who used cadaveric material attend the service with donors families from the past year as a chance to honour and talk about those who gave their lives.

The university also has a memorial book where each donor’s name is inscribed.

Mr Parson said: “We often receive donations from husbands and wives, friends from small communities and the families of previous donors, which indicates to me the importance of awareness and discussion in making this selfless decision.

“We receive a smaller number of donations than some of the metropolitan conurbations of the central belt, which is largely due to population differences and the low and dispersed population of the rural north and north-east of Scotland.

“We are always keen to gain new donors who wish to help medical education and training and an increase in donations would allow us to further expand opportunities in postgraduate medical and surgical education, where practitioners can learn cutting edge skills in a safe environment.”

To register to make a bequest visit the university websites to find out more.

How are body bequests used?

There are a variety of uses for cadavers in medical research including anatomy lessons, operation practice and dental tests.

By using real bodies, it is thought by professionals that students are learning more and have an increased understanding of their work after using the cadavers.

Common question often arises though – how these bodies are kept and used without deteriorating.

When a body first arrives at the university, which has to happen within a certain period of the death, it is put through an embalming process.

Professor Tracey Wilkinson, principal anatomist at Dundee University, said: “In Dundee we use a completely different embalming system which is called Thiel and people seem to choose to donate to us more because of this as it means our bodies are much more flexible.

“Traditionally people donated their bodies for medical students and around half of our cadavers are used by a whole range of people learning human anatomy through dissection.

“The other growing side of body donation that’s grown more in recent years is for surgical and clinical skills training – essentially people can practice operating on real bodies and with our Thiel system the bodies are very life like.

“We can also use cadavers to test future surgical methods.

“Cadavers are fantastic as they can be used in ways that make it appear like the body is breathing, the heart valves pumping, artificially making the body react how a human would.

“If you make a mistake it doesn’t really matter.

“To me, donated bodies are the Mercedes-Benz of medical simulations.”

But uses for bodies do not end at the teaching of students.

In Dundee in particular, bodies are used to test medical devices.

Ms Wilkinson said: “If a biomedical company has come up with an innovative idea then we can use cadavers to test them.

“There are some amazing prosthetics and other developments like pace makers which we can assess using the cadaver.

“To me, a person saying we can use their body when they die to contribute to science and really help the next medical generation as well as with life-saving devices is incredible.”

Donating your body and the idea it can do some good

Tamsin Gray – I registered my bequest last year after thinking no other method of deterioration sounded appealing.

With a mum who studied using cadavers, I was told stories about how much she learned from them during her university days.

So when the time came to write a will, as you’re encouraged to do once you buy a house, I sought more information on donating my body to medical science.

Finding out that more than 20,000 people in Scotland have registered to donate was heartwarming.

Students often work on cadavers in groups, with certain body parts being used for different classes.

Currently, if use of cadavers was exclusively for medicine first year students in Aberdeen University, there would be one body shared by five students, an increase since 2015 where more than six students would share the cadaver.

To me, being useful in the teaching of five new doctors who could save lives sounds much more palatable than being buried or cremated.

At the end of the few years the universities use the body for, they hold a ceremony where the students meet the families and can talk about what they learned using the cadavers.

Knowing my family will be reassured I went to good use also seems appealing.

Dundee University’s Professor Tracey Wilkinson said: “Usually it’s older people thinking about the end of life who register or people who knew others – we’ve some lovely family cadaver groups here.”

When she added: “At 23 you’re very young to have registered,” I was surprised.

But knowing 20,000 other possible bodies will be helping advance medical science is definitely reassuring.