She was the Aberdeen woman who wrote a groundbreaking book about botany in the 18th century.

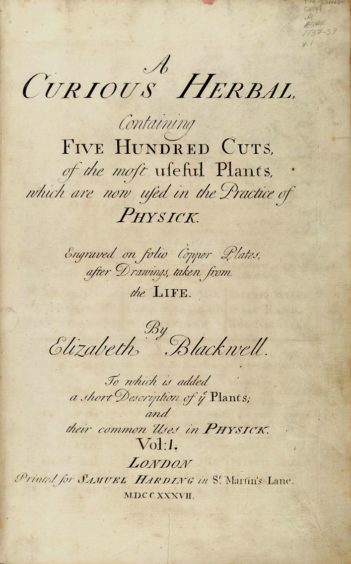

And even today, Elizabeth Blackwell, who created A Curious Herbal, the first work of its kind ever to be produced by a woman, is still regarded as a trailblazer in her field.

Aberdeen University holds an original edition of the beautifully-crafted volume which highlighted Mrs Blackwell’s keen powers of observation and scientific knowledge .

North-east storyteller Amanda Edmiston has provided fascinating insights to the Press and Journal about the fashion in which Mrs Blackwell both sparked controversy and attracted acclaim for her endeavours throughout Europe more than 280 years ago.

She was born in Aberdeen to the wealthy Blachrie family and received a good education which included tuition in art, music, and languages.

But she scandalised Granite City society and broke with convention when she married her debt-laden cousin Alexander and the pair were abruptly forced to leave their roots.

Although Mr Blackwell was well educated – his father and brother had both served as principals of Marischal College in Aberdeen – and practised as a physician, he never bothered to acquire any formal medical training.

When his right to call himself a doctor was subsequently challenged, the couple fled from Aberdeen to London.

After working briefly with a publishing company, he set up in business as a printer, but incurred hefty fines, which he was unable to pay. As his financial problems continued to mount up, he was finally sent to Highgate Prison.

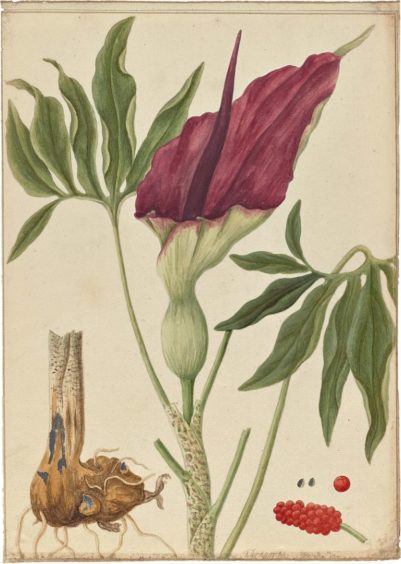

A talented draughtswoman, Mrs Blackwell had held an interest in drawing plants since early childhood. Motivated by a dogged determination to raise the bail money for her husband’s release, she produced some sample drawings.

When she showed these to the distinguished Sir Hans Sloane and Dr Richard Mead of the Royal College of Physicians at the renowned Chelsea Physick Garden, they were both impressed and encouraged her to produce more work towards a formal herbal.

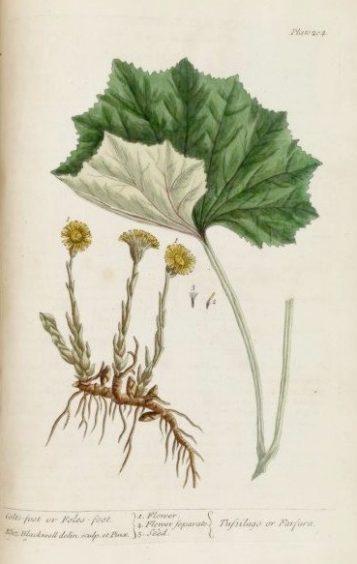

This is a book of plants, which describes their appearance, their properties and how they may be used for preparing ointments and medicines.

Mrs Blackwell drew plants from life and took the pictures to her husband in his debtor’s cell where he provided the Latin names and descriptions.

She then engraved the copper plates for printing and finally hand-coloured all of the printed images – an accomplishment which would usually have taken at least three different artists and craftsmen.

Her work, A Curious Herbal, was a huge success and received endorsements from some of the most eminent scientists of the time.

The final book contained 500 illustrations which were published in 125 weekly instalments from 1736-39 and it also became known across Europe.

An enlarged version called Herbarium Blackwellianum was published in Nuremburg. And Carl Linnaeus, the famous Swedish botanist, was aware of Elizabeth’s labours and gave her the title of Botanica Blackwellia.

Its publication also achieved her desired outcome and she was able to pay for Mr Blackwell’s release from jail in 1739.

Sadly, her husband did not return her loyalty. Unable to live within his means, following a number of unsuccessful business ventures, he left for Sweden and was alleged to have become embroiled in a plot to overthrow King Frederick I.

He was executed in 1747, just days before his wife was due to join him.

Little is known of her later life. She died in 1758, outliving her three children, and was buried in Chelsea.

Mrs Edmiston said: “I first discovered Elizabeth Blackwell when I was commissioned to create a workshop for the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons in Glasgow and saw their 1737 copy of A Curious Herbal.

“I felt an immediate connection to her as, not only were we from the same city, but clearly both loved plants.

When I discovered she had created the book to support herself and her child and that she had drawn from the plants in Chelsea Physick Garden, I felt a little shiver.

“As you can imagine, I really wanted to tell her story and bring together stories of all the plants she illustrated, so the project is weaving together Elizabeth’s story, snippets of history, traditional uses of the plants, the recipes she might have known along with stories and folklore about the plants themselves.”