She is somebody who has witnessed the worst of human behaviour and investigated the casualties of genocide in Kosovo, ethnic cleansing in Iraq and natural disaster in Thailand.

She has also assisted the police in examining the victims of sex crimes, travelled to Grenada to work with the US military in a climate of insurrection and delved back into the mists of time while providing links between the past and the present.

Yet, even though Professor Dame Sue Black has amassed all manner of accolades and academic distinctions, on the road from being born in Inverness to graduating from Aberdeen University and gradually becoming an internationally-renowned expert in forensic anthropology, she has never lost her fascination, her curiosity or compassion with the process of analysing the only certainty in all our lives.

As she explained, her work requires a methodical, endlessly meticulous capacity for taking pains. The tabloids might have labelled her Sherlock Bones, she starred in the BBC series History Cold Case and she has a hinterland, encompassing everything from the music of Gerry Rafferty to Glenn Miller and the Corries to Cher, but any semblance of levity vanishes whenever she embarks on another assignment.

As she said: “The truth is that you never lose track of the fact that the person in front of you was someone’s son or daughter, mother or father, brother or sister.

“You think about how you would wish your own to be treated if the roles were reversed and you act according to that moral and ethical obligation.”

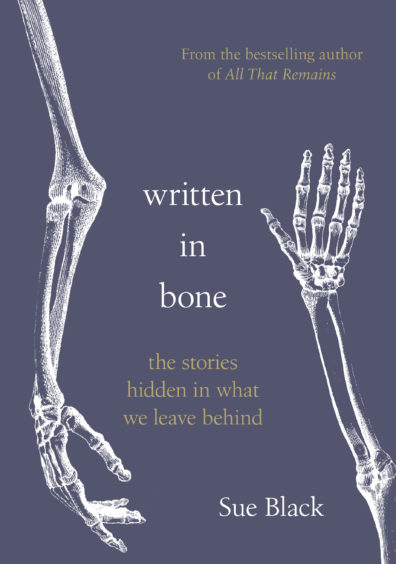

It’s a mantra which has served her well throughout her peripatetic career and which she has documented in a compelling new book Written in Bone.

This includes the time in 1999 when Professor Black was sent by the British Government to analyse the discovery of a group of unidentified corpses in Grenada after they had been unearthed by a local gravedigger in the region.

Word soon spread that these remains included the body of Maurice Bishop, the leader of a revolution in his homeland in 1983, which had sparked political anarchy and the subsequent invasion of the island by the American military, on the orders of President Reagan.

The rumours about the potential finding of Bishop’s body were the catalyst for civil unrest in Grenada and the US quickly assembled a task force, comprising military personnel and FBI investigators, to address the matter.

The UK, meanwhile, sent the redoubtable Prof Black to the scene and, as she said: “The contrast between the Brits and the Americans could not have been more striking.”

In one corner was a massive group of high-ranking US representatives, dressed in “corporate jackboots” with the latest cutting-edge technology. In the other stood a single flame-haired Scot with the minutiae of anatomy and an encyclopaedic knowledge at her fingertips.

It was no contest.

As Prof Black told the Press and Journal: “Every case is a challenge and every outcome is a reward. At all times, we focused on the questions being asked of us: ‘Could these be the remains of Bishop and his Cabinet?’

“It became very clear that this was not the case and so the secondary question was: ‘Who do these remains belong to?’

“Being able to tie what we were seeing with historical accounts of casualties (civilians at a nearby hospital who were killed in a US air strike) allowed the remains to be reburied and formal notification made of them, so that they would not be disturbed again.

“That was really important.”

The affair was rather like Miss Marple stepping into an X-File. But the fashion in which she found solutions demonstrated the qualities which this stalwart Scot brings to her vocation.

Her infinite attention to detail spans centuries. And she was fascinated while spending time studying the remains of crew members of the famous ship, Mary Rose, which was prominent in Henry VIII’s navy after being launched in 1511 before sinking in battle in 1545.

The expertise of her colleague, Anne Stirland, revealed secrets of those who died, but only after the most rigorous scrutiny. From skull to feet, via the face, spine, chest, arms, hands, pelvis and legs, the pair realised that every human action leaves a trace, a message that can wait for months, years and, in this case, centuries until it has been deciphered.

The findings were both poignant and telling: they showed that many of the sailors on Mary Rose might have been in the prime of life – but they were suffering from arthritis.

Prof Black explained: “This was true even though most of these men were very young. What was most interesting was the ‘os acromiale’, where the little nub of bone the ‘acromion’ never fused to the main body of the bone.

“This showed that young people were putting an inordinate amount of strain through their shoulders. And the most likely explanation for that was to do with archery.

“It takes a lot of time before you can think about taking on some areas of casework. It is not swift, but then no genuine profession is.

“You have to learn your trade and then you have to be able to prove that you have achieved the necessary experience to be able to give a professional opinion in a court room.”

Prof Black, who spent 15 years at Dundee University prior to moving to Lancaster, is not sentimental about her work. She can’t afford to be when she is dealing with the consequences of such large-scale and grievous disasters as the tsunami which devastated Thailand on Boxing Day in 2004.

She and her team at the Leverhulme Research Centre for Forensic Science developed a range of new techniques, which included identifying child abusers through vein and skin patterns.

Their efforts resulted in the conviction of Scotland’s largest paedophile ring in 2009 and the subsequent conviction of Richard Huckle, the UK’s most prolific paedophile.

As her new book reveals, this was a subject very close to home.

On the body of an 11-year-old child who had taken his own life, she discerned some ‘Harris lines’: marks in the bone where normal growth has been arrested, usually because of severe illness or trauma. And these corresponded to periods when the boy was in the care of his grandfather.

It was a throwback to her own distress when, at the age of just nine, she herself was brutally sexually assaulted in an act where she “lost her childhood”.

It’s now 50 years since that happened, but the memories are seared on her consciousness and understandably left her “in a dark and lonely place”.

As she stated, in matter-of-fact fashion: “My mental Harris lines will remain with me for the rest of my life.”

Ever since, she has been tirelessly committed to gaining justice for those who have been denied it. A principle which has steered her through stormy waters all over the globe without knocking her off an even keel.

Prof Black was understandably delighted when she attended the graduation of her daughter Anna – with a first-class honours degree – at Aberdeen University last summer.

Not only did the youngster celebrate her big day, she also saw her mother receive an honorary degree, and spoke about the family’s commitment to being the best they could be.

Anna said: “She has to be one of the most hard-working people I have met. It is a rare opportunity that a mum and daughter can graduate together and we feel very honoured.”

These words were reciprocated by the woman who was to became a Dame in 2016, as she offered some guidance for anybody interested in following in her distinguished footsteps.

She told me: “My first advice is always to forget the ‘forensic’ bit. That may come later. But you need to be a scientist first.

“Biology is the most appropriate science for training as a forensic anthropologist and I would strongly recommend either human anatomy – with full body dissection – or, as a second best, biological anthropology or osteoarchaelogy.

“There is no substitute for learning all the tissues of the human body and how they interrelate – so human anatomy is the best training, in my opinion.

“Then I would consider a postgrad training programme in forensic anthropology and most who practice will go on to do a PhD. So it’s a minimum of six, but more likely up to nine years before you will be ready to think about taking on some areas of casework.

“And, even then, you will need to be mentored by a certified practitioner so that you can gain your own certification status. But I have found it immensely rewarding.”

It might have been a long and winding road since she started a Saturday job in a butcher’s shop in Inverness, after leaving primary school in Lochcarron.

But the resourceful Prof Black has already taken steps to guarantee the journey will continue to be worthwhile even after she has shuffled off this mortal coil – by ensuring that her body is given to Dundee University to teach future generations of students.

As she said: “If I achieve my aim, I will never really die, because I will live on in the minds of those who love anatomy and fall in love with its beauty and logic, just as I did.”

It is a subject that not many people want to discuss. But Prof Dame Sue Black has peered into the abyss and found that whatever remains can leave a legacy.

Written in Bone is published by Doubleday on September 3.

Dame Sue Black’s life in lockdown

“I am very lucky,” she said.

“At the end of March, I came home to Scotland to be with my family (in Stonehaven) as I continued to work.

“I am amazed at what can be achieved through digital means and I would not have believed it before the crisis.

“It is a challenging time for everybody and universities are no different. We want our students to return to their studies, but we also want to be able to keep them safe.

“There have been tremendous alterations to the way we teach and the way in which we research. I hope that normality will return soon, but I think there have been some aspects that will have changed us more permanently and some of them are good.

“The current crisis will have helped a lot of people to reassess what is important in their lives and I have seen genuine acts of selfless kindness that remind us about the good in humanity when the chips are down.”