There were no shortage of bold plans devised to improve the quality of Highland railways during the Victorian era.

But the majority of the projects were consigned to oblivion because of political arguments, petty rivalries, business obstructionism, the blight of ‘Nimbyism’ and struggles between public bodies and private landowners.

The title of a new book – A Quite Impossible Proposal – sums up the attitude of some civil servants and mandarins in London, who regularly frustrated efforts by Scottish designers and engineers to improve the transport network in the north.

Its author Andrew Drummond has spoken to the Press and Journal about how the philosophy of stubborn bureaucrats offered a template for “how not to build a railway” in parts of the country where it would often have been a blessing.

If these proposals had come to fruition, there might have been direct rail links to island communities and the capacity for breaking down cultural and tourism barriers.

Instead, they turned out to be the railways which swiftly hit the buffers.

The author, who was born in Edinburgh and educated at Aberdeen University and King’s College in London has published a number of acclaimed works of fiction and non-fiction and seems comfortable in either genre.

He also has a fascination with the minutiae of machinery, the golden age of train travel and the trailblazing figures who orchestrated dazzling new transport schemes.

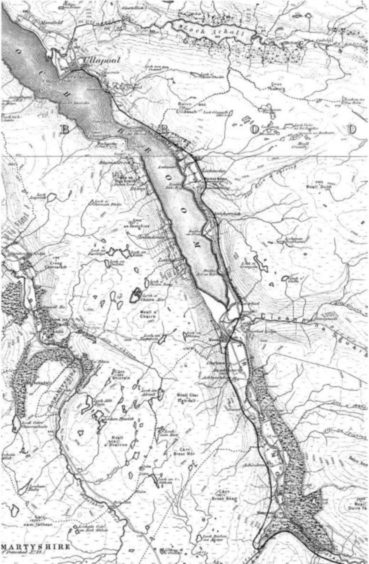

He said: “My interest in these railways goes back a long way. Around 2000, I stumbled across a reference to a planned railway for Ullapool in 1890. Knowing the area quite well, I was at first doubtful. But I did some investigation and found it to be true.

“The result was a fictional treatment – my novel ‘An Abridged History’ in 2004, which imagined that the railway had indeed been built.

“A couple of years ago, I was planning a new edition of the novel and thought I should really do some more research – the more so, since I had been advised by residents of Ullapool that there had been a renewed proposal for that railway in 1918.

“Almost as soon as I began my research, I was away down a rabbit hole. There had been not just one never-built railway to the north-west, but four – and that’s not to mention two on the islands.

”And there wasn’t just one attempt to build the Ullapool railway, but five, over a period of 65 years. The more I looked at it, the more material I uncovered.

“And the more I uncovered, the broader the story became: this was not just about railways. It was about poverty and social injustice, it was about the ownership of land, it was about fish and it was about the attempts of the people of the north-west to take a share of the benefits of late 19th and early 20th century life.”

Mr Drummond has investigated the background to all the different schemes, against the backdrop of the region’s economic and social problems, allied to civil unrest in the stricken crofting communities.

And what emerges is the scale of the schism between people living in the Highlands and those who dwelled in the corridors of power hundreds of miles away in London.

He said: “When it came down to it, only two of the four proposals for mainland railways ever had a chance of succeeding.

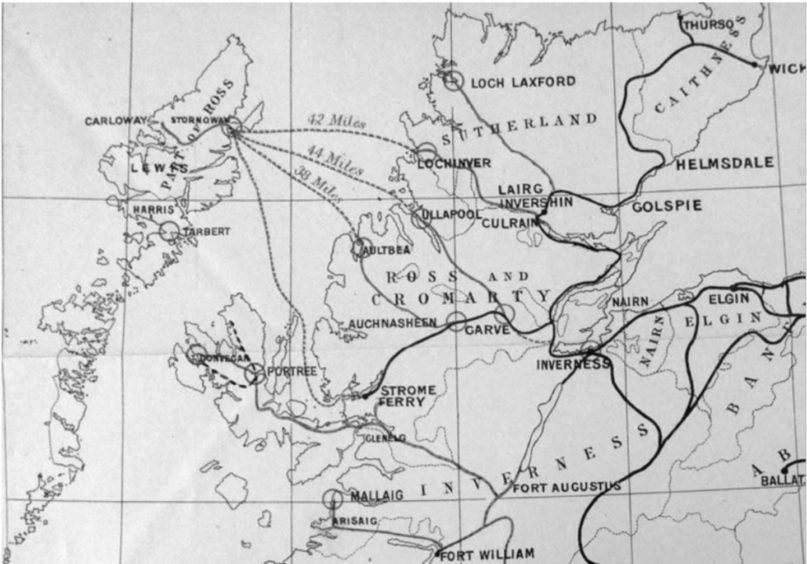

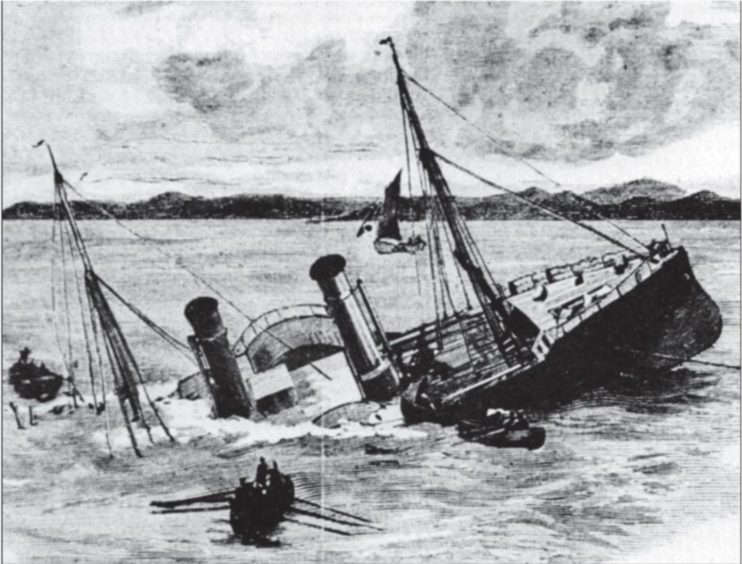

“One was the Garve-Ullapool line, the other the Achnasheen-Aultbea one. Both of them ended up at a point on the coast which was convenient for steamer traffic to and from Stornoway, which was precisely why any railways were being considered.

“Stornoway was the capital of the west coast fisheries and fish had to get to the English markets quickly, so the north-west needed a railhead.

“Neither of those two lines would have been particularly easy to construct. But I have great faith in the ability of Victorian railway engineers to build difficult lines – just witness the railway which still runs over Rannoch Moor, further south.

“My own preference is for the Ullapool route, but that is partly my heart winning out over my head. If that route had been opened, then the benefits – social and economic – for both Ullapool and the surrounding area, as well as for Stornoway and the Isle of Lewis would have been immediate and far-reaching.

“The fact that the line was not built meant that Ullapool languished in peaceful retirement well into the 1970s, when the Stornoway ferry was finally introduced.

“Ullapool has very obviously thrived since then, but it’s just a pity that it could not have happened several decades earlier. And even today, there is a very strong argument for a better and more sustainable connection between Inverness and Stornoway – designed for freight as well as for passenger traffic.

“The A835, handsome though it is, is really not good enough for 21st century traffic.

“Railways were also planned for Skye and Lewis and of those, I think that the Skye one in particular would have brought significant benefits to the island.

“Not that Skye has remained a backwater for want of a railway, of course. But, again, it would have been an enormous social and economic benefit at the end of the 19th century. And what a tourist attraction it would be today.”

The book makes it clear that the Highland population grew incredibly tired with having their schemes dismissed at regular intervals.

Despite the involvement of some of the most experienced architects and engineers in the Victorian age, including Sir John Fowler who was instrumental in the creation of the Forth Bridge, and Inverness stalwart Murdoch Paterson, the response from the Scottish Office was usually negative, as history kept repeating itself.

Mr Drummond said: “Several local heroes stand out in these tales, people who brought energy and commitment to the idea of having a railway built.

“As with almost all things Victorian, they were men – sadly, women were either excluded or ignored or left unrecorded in the process.

“For the Ullapool proposal of the 1890s, a gentleman named P Campbell Ross was an indefatigable writer of letters, drafter of petitions and castigator of all opposition.

“Not much is known about him – he was the son of a local Wee Free minister and some of his letters to the high and mighty down in London bear witness to his father’s tradition of sparing no one in a quest for righteousness.

“It was he who described (to a government minister) the report of one Whitehall Commission of Inquiry into railways as ‘drivel’.

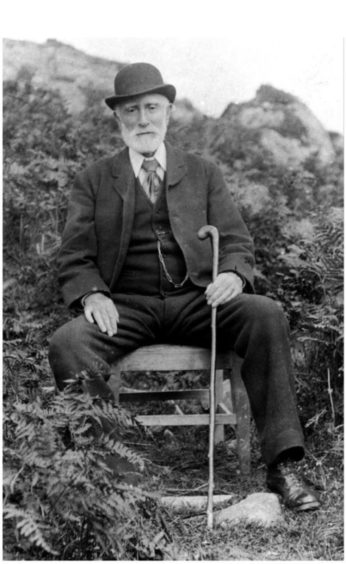

“But he was quite correct. Ross received moral support from the Fowler family, whose estate lay at Braemore. This was the estate purchased by Sir John, the designer of London’s Metropolitan Line and co-designer of the Forth Bridge.

“Sir John – but more particularly his son Arthur – lobbied endlessly with colleagues and acquaintances in the higher echelons of society.

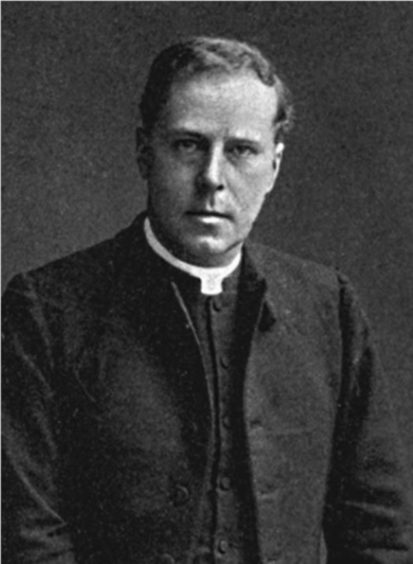

“In 1918, it was another son of Sir John, the Reverend Montague Fowler, who did his best to persuade the government of the advantages of the Ullapool railway.

“Further south, the Achnasheen to Aultbea railway was heavily promoted by John Henry Dixon, a retired lawyer who spent several happy years doing much the same as Ullapool’s Ross – writing letters, drafting petitions, compiling reports and generally making a nuisance of himself with the people in Whitehall.

“While Ross and Dixon were the visible agitators, none of what they did could have happened without the relentless and vocal support of local fishermen, crofters, ministers and teachers, who all took the time to attend meetings, sign petitions and generally make it known to the authorities that they wanted a railway.

“These voices were particularly loud on Lewis, where ‘Ullapool’ and ‘Aultbea’ factions were formed, and it occasionally turned into fisticuffs between the parties. Most of these men and women are unnamed in the archives. But it was the popular support which drove the proposals forwards.

“And who was the most obstructive? By a country mile, it was the board of the Highland Railway Company, and in particular their General Secretary, Andrew Dougall.

“The Highland Railway was based in Inverness and it owned and operated the railway to Edinburgh, the railway to Wick and the railway to Strome Ferry (and later to Kyle).

“What they did not want was anyone else siphoning off the traffic to the west coast, and Dougall did his utmost to prevent it.

“Some of his methods were more subtle than others. But equally adept at raising obstructions – but without even the excuse of knowing they were doing so – were a succession of Secretaries of State for Scotland, who generally seemed incapable of understanding what was wanted.

“Even in cases when they did understand, they were not willing to lift a finger to help.

“For several years, Whitehall-funded commissions of inquiry set out to the north-west to look into matters and make suggestions.

“Most failed abysmally in their task, combining geographical ignorance with an ingrained belief that the local population did not really deserve anything better.”

Mr Drummond’s views will strike a chord with many people.

He accepts that railways might not always be a universal panacea or even offer a practical lifeline in places with diminishing populations. But they have usually bolstered their communities.

And, as he said: “In the late 19th century, it was an accepted fact that they were the most efficient method of transport and could deliver economic and social improvement.

“The engineering might have been difficult in some places along the route, but the Victorians were nothing if not good at elegant engineering solutions.”

It’s a classic tale of what might have been, of squandered opportunities, and an abundance of red tape transcending white-heat technology.

No wonder the author has chosen to rail against the opponents of progress.

A Quite Impossible Proposal is published by Birlinn Books on September 24.