It’s a book that is dedicated to her family and includes a word of apology.

“This might explain all the times I wasn’t there. Sorry.”

Yet, as one reads through the grisly, gruesome accounts of often terrible crimes chronicled in Beyond the Tape, the life and many deaths investigated by Glasgow-born Dr Marie Cassidy, whether in her homeland or after she became Ireland’s first female state pathologist, one’s admiration increases for this tenacious, trailblazing woman.

It isn’t just the humanity and decency that illuminates her account, even when she was working as a consultant pathologist in the department of forensic medicine and toxicology in Glasgow from 1985 to 1998; a period where she probed myriad unnatural deaths and homicides, from gangland shootings and stabbings to drug fatalities, road accidents and suicides.

But there is also the professionalism and hours of meticulous work she devoted to justice, as she carried out hundreds of post-mortems and analysed some of the worst acts that have ever been carried out by human beings.

As she remarks, halfway through her new book, there were 92 murders in Glasgow in 1992 and she ended up seeing more of her colleagues than she did her own family.

And she was also involved in the exhumation of John McInnes, the man who was suspected of being the serial killer Bible John.

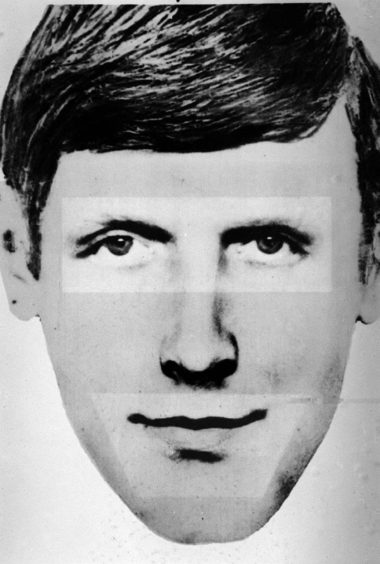

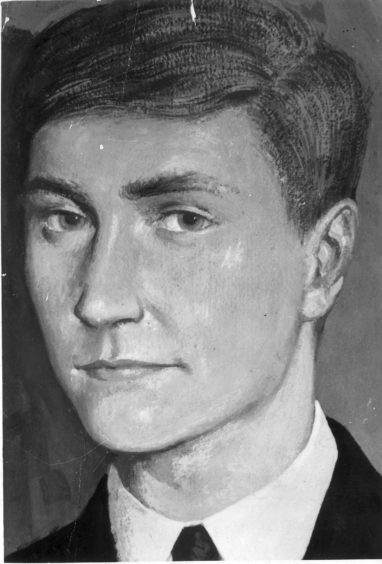

This notorious individual had roamed the Barrowland dance hall in the late 1960s, picking up women who were later found dead, battered, strangled and sexually assaulted.

He gained his religious moniker because the people who had been with the victims recalled how the attacker, who gave his name as John, was accustomed to quoting from the Bible and decried allegedly adulterous females who attended dance venues.

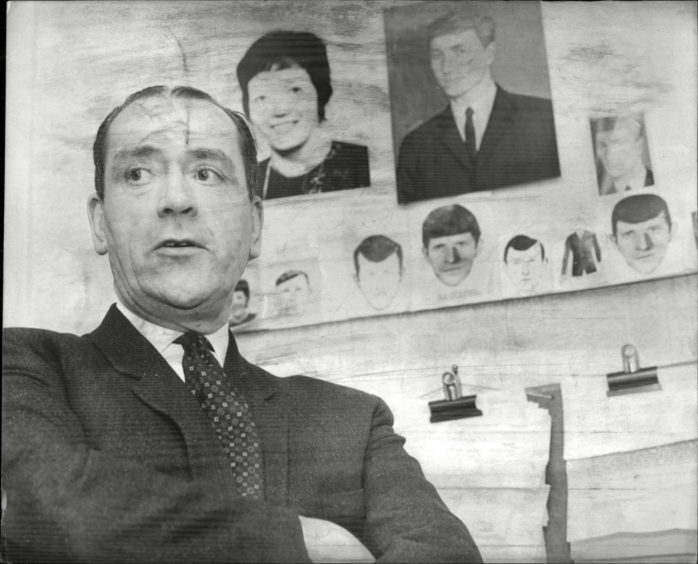

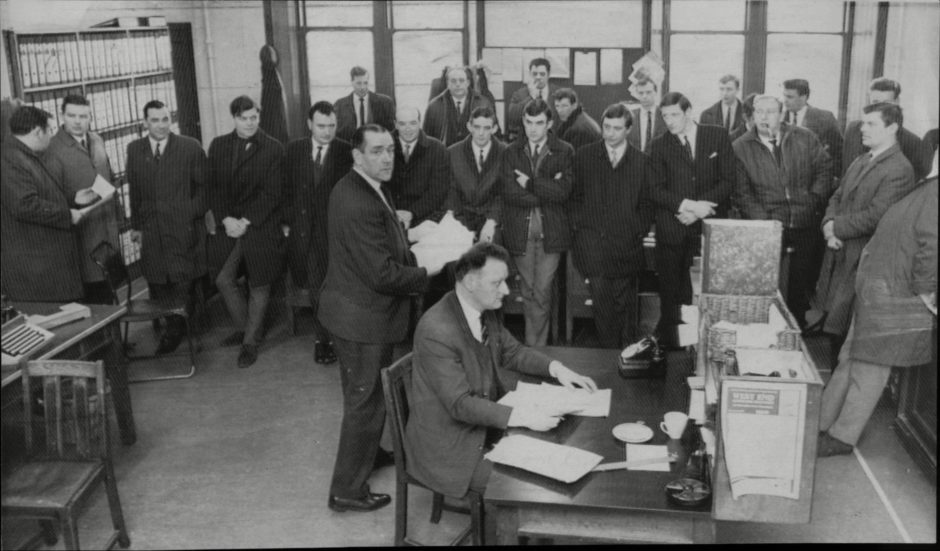

Even now, more than half a century later, his crimes still chill the blood. But Dr Cassidy wasn’t deterred by the fact the police never identified him, despite a massive manhunt.

She said: “I became involved as the forensic pathologist acting for the Crown Office. In the mid-1990s, advances in DNA analysis meant that the police began reviewing unsolved cases where there was a possibility that stored evidence could identify a perpetrator.

“One of the suspects in the Bible John murders was John McInnes. He fitted the suspect’s general description and was said to have been sighted in the Barrowland.

“He had been included in an identification parade, but had not been picked out by women who had come forward with information about the man last seen with the murder victims.

“The police believed that circumstantial evidence linked McInnes to the murder of one of the women, Helen Puttock. He had committed suicide in 1980, which might account for the sudden end to the reign of terror in the Barrowland.

“In 1993 Helen’s death was reviewed. A semen stain had been identified on her clothing at the time of the original identification, but now technology enabled a DNA profile to be obtained. John McInnes’ siblings were informed of the ongoing investigation and consented to swabs being taken from them for analysis.

The police believed that circumstantial evidence linked McInnes to the murder of one of the women, Helen Puttock. He had committed suicide in 1980, which might account for the sudden end to the reign of terror in the Barrowland.”

“The experts were of the opinion there was sufficient similarity between the siblings’ profiles and the semen stain to proceed with the investigation, and a decision was made to exhume his body and take samples for DNA analysis.

“Professor Tony Busuttil was observing proceedings on behalf of the family of the deceased and I was the forensic pathologist for the Crown. Exhumations are usually scheduled for dawn or thereabouts, an unearthly hour, but the hope is that we can get in and out as quickly as possible, in particular before the press are alerted to our activity.

“These are very difficult operations. The adjacent gravesites must not be disturbed, which makes it hard to access the grave of interest. There are also variables: how many bodies are in the grave, their order of interment, when the body was interred, the state of the coffin and the soil conditions.

“In this instance, we had to dig down a considerable distance to access the relevant coffin. The first contained the body of Mrs McInnes, John’s mother, who had died seven years after her son. All care was taken that this coffin was recovered intact and removed to the funeral parlour, awaiting reinternment.

“The excavation continued and the next coffin was struck. Neither Tony nor I is particularly tall and I had to be lowered into the grave to confirm that we were dealing with the correct coffin and body.

“Tony elected to remain at the graveside, but even this was hazardous and he found himself slipping into the hole and he was grabbed at the last second by the police.

“Manoeuvring a coffin out of a grave is difficult as the clearance is only a few centimetres, but eventually we were successful.

“The remains were removed to the mortuary and bone samples were taken: the best source of material for DNA analyses, given the timeframe involved.

“Unfortunately, despite our best efforts, the laboratory could not get a full profile and the results were described as being inconclusive.

“The Barrowland serial killer had not been identified and remains unidentified to this day.”

TV portrayal

Dr Cassidy’s work and her philosophy that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains is nowhere near as glamorous as how it is often portrayed on television dramas.

Indeed, although she believes Taggart was probably most accurate in its depiction – not least because she was a consultant on the programme for several years – it is obvious she has scant regard for a number of more recent TV productions, where the pathologist doesn’t just dissect a corpse, but subsequently joins the police to highlight their shortcomings and solve the crime – all in the space of a couple of hours.

Naturally, fiction writers tend to cut corners and employ dramatic licence and Dr Cassidy believes this has sparked confusion among many people about what her former job entails.

She said: “When Silent Witness came along in 1996, the lead (played by Irish actor Amanda Burton) was a female forensic pathologist, which reflected the increasing numbers of women attracted to a career in the discipline.

“But they had to beef up the part and suddenly the forensic pathologist was the key figure in murder investigations, not just one of the backroom boys or girls.

“Routinely, Dr Sam Ryan was seen questioning witnesses – as if the police would ever let a pathologist near one.

“Since then, there has been some confusion as to what we do, but the answer is simple.

“We carry out post-mortem examinations to establish the cause of death, even if it appears blatantly obvious in some cases and, in doing so, identify deaths due to homicide.

“The whole system of death investigation was largely designed to prevent homicides going undetected, but now it is more all-encompassing and plays an important role in monitoring the health of the population.”

Knowledge and expertise

As somebody who has held senior posts in Scotland and Ireland, Dr Cassidy has grown wearily accustomed to being asked how easy it it to advance into the world of CSI. It’s not and she had to study for many years in the process of acquiring and developing the breadth of knowledge and expertise she has brought to her vocation.

Predictably, there is another inquiry which she confronts wherever she travels and although she is now retired and living in London, Dr Cassidy has sufficient savvy to swat it away.

She explained: “As for the other question – the most gruesome case I’ve seen – it is usually male transition-year students or budding psychopaths who ask me.

“I dodge that one, because, sure as Fate, Mammy would be on the phone claiming I had traumatised her darling son – or the details would be on the front page of The Sun (which has happened).”

There are echoes of Professor Dame Sue Black in Beyond the Tape, so it’s hardly surprising that these two redoubtable Scots meet up in the very first chapter, as part of a United Nations peacekeeping force in Sierra Leone in 2000.

Their mission was to recover the bodies of a small group of UN soldiers, who had been killed in the conflict and determine how they had died and identify these troops. It turned into a fraught assignment, so much so that Dr Cassidy revealed: “A shiver ran down my spine. How on earth did I end up here?” even as two large vultures stared down at her mortuary.

But, as in the rest of her long and distinguished career, she persevered and did her job. Temperamentally, she is as fragile as a moose.

Beyond the Tape is published by Hachette Ireland.

Dame Sue Black on working with Dr Marie Cassidy

Renowned forensic anthropologist, Professor Dame Sue Black has joined forces with Dr Marie Cassidy on several occasions and the pair have a close bond.

The Inverness woman, who worked at Dundee University for many years, said: “Marie and I worked together on a number of cases both in the UK and overseas.

“Marie is tremendously good company and a highly respected pathologist spoke highly of her compatriot.

“She is a tiny woman who packs an enormous punch. I remember when we were sent over to Sierra Leone to work together, she arrived with nothing more than hand luggage whereas for my heft, I needed a good-sized suitcase.

She is a tiny woman who packs an enormous punch.”

“It is funny the things you remember. We worked closely together on a number of cases when we were both in Glasgow and it was a real delight.

“She has a wicked sense of humour but an impressive moral compass.”