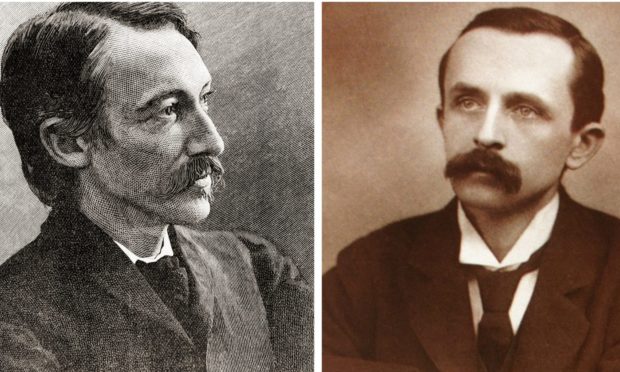

They are two of Scotland’s most famous authors; the men who created such masterpieces as Peter Pan, Treasure Island, Kidnapped and the Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

And although JM Barrie and Robert Louis Stevenson never met, they developed a warm friendship, engaged in a long-distance exchange of letters between Britain and the Pacific Islands, and have left behind a treasure trove of playful and poignant missives.

Until recently, Barrie’s side of the correspondence had been presumed lost by his biographers.

But Dr Michael Shaw, a lecturer in Scottish Literature at Stirling University, came across the precious manuscripts while on a research trip, and has been enchanted by their contents.

He has now collected and put them in context in his new book A Friendship in Letters and spoke to me about the work, which not only includes a series of amusing, gossipy and revealing perspectives, but also a short story by Kirriemuir-born Barrie in which he imagines a highly entertaining meeting with his compatriot.

Samoa

The latter is a particularly evocative piece because he had intended to travel to Samoa to meet Stevenson, only for the latter to suffer a fatal cerebral haemorrhage at the age of just 44 in 1894.

Yet, as Dr Shaw revealed, all this material had lain in an American library for decades until he carried out some detective work which was worthy of one of Barrie’s contemporaries – and cricket teammates – Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes.

He explained: “I had gone to the Beinecke Library in Connecticut in 2016 to look at some specific manuscripts on Stevenson, Barrie and Andrew Lang.

“I had some time on my hands, so I requested boxes of material which looked interesting.

“The Barrie letters were in one of these boxes – all fully catalogued and clearly labelled – and I simply assumed that they must have been published before and it had somehow escaped me.

“So I took the opportunity to read through them and then resolved that I had to get hold of a printed copy of them.

“It was only when I started looking for them and researched the correspondence that I realised they hadn’t been published and that some biographers and editors had suspected the letters were lost.

“I think it was when I read Viola Meynell’s note that Barrie’s letters to Stevenson were ‘lost or destroyed’, in her Letters of JM Barrie volume (from 1942) that I felt some real excitement.

“But it developed gradually and it only happened after a fair bit of work.”

Renowned Scots

Dr Shaw admitted it might seem surprising to many modern readers that these two renowned Scots never once crossed paths.

After all, they were eminent Victorians who networked in literary circles, and were taught by the same professors at Edinburgh University.

However, while they would both have been in the Scottish capital at the beginning of 1879, as Barrie started studying for his MA degree, Stevenson spent most of his time away from Auld Reekie in America and the Scottish Highlands.

Thereafter, by the time Barrie’s star was on the rise in the late 1880s, his compatriot was living in the United States and subsequently embarked on the journey which resulted in him settling in Samoa.

When their friendship began in earnest in 1892, Barrie was staying in his birthplace, visiting close family members, especially his elderly mother, whom he went on to memorialise in his book Margaret Ogilvy, and his sister Maggie.

Dr Shaw said: “It was still more than 10 years before Peter Pan was staged in 1904, but Barrie was nevertheless a well-known writer on both sides of the Atlantic.

“He has recently published two books A Window in Thrums and The Little Minister, which were set in the fictional Scottish town of Thrums, which was a thinly-veiled depiction of Kirriemuir, and Barrie went on to write several bestsellers set there over the course of the 1890s.

“While he was best known for writing prose, he was also starting to show his prowess in the theatre.

“This move didn’t just mark the beginning of a shift in his professional life, but it was also a turning point in his love life.

“He became infatuated with Mary Ansell, an actress, and they were married two years later in Kirriemuir. At the time of their marriage in 1894, when Stevenson and Barrie had become very close friends, the Edinburgh Evening News reported that the newlyweds were intending to visit Samoa (although circumstances conspired to ensure the trip never happened).”

Genuine connection

As it transpired, the duo didn’t need any introductions to forge a genuine connection; one which is illuminated on every page of Dr Shaw’s book, which conveys their feelings about friends, family, acquaintances, occasional bete noirs and covers everything from their writing process to politics, sport and art.

At its heart, and despite the fact that both these lustrous literary figures had strong passions for the female sex, this is a love story between two men, one which flourished even though they were divided by continents.

In one letter, Stevenson writes that Barrie had the second-worst handwriting he had ever encountered, but that’s as far as the criticism goes.

Elsewhere, the tone is, by turns, witty, competitive, enlightening, analytic and often highly personal in nature.

Dr Shaw said: “I was initially intrigued by the length of their letters, especially towards the end of correspondence and some of them run to around 3,000 words.

“Stevenson’s friend, Sidney Colvin, described one of them as a ‘journal letter’ which is a good description.

“I was also intrigued by Barrie including a playlet in four acts in one letter – where he imagines his visit to Samoa – and a humorous family tree, showing that his and Stevenson’s characters were related.

“I think these details revealed the extent of Barrie’s love for Stevenson and how desperately he wanted to travel to Samoa, which is reflected in the way that he wrote about Stevenson after the latter’s death.

“I certainly hadn’t understood the depth of his affection – and its impact on his writings – before working on the correspondence.”

Tales from Doyle to Downton Abbey

Arthur Conan Doyle became a close friend of Barrie and visited him in Kirriemuir during Easter in 1892.

As Dr Michael Shaw noted, they were both cricket fanatics and the Sherlock Holmes creator was a member of Barrie’s team, who were affectionately known as the Allahakbarries, and also featured the likes of Rudyard Kipling, HG Wells, Jerome K Jerome, AA Milne and PG Wodehouse.

Together, the duo collaborated on an unsuccessful opera venture, Jane Annie, in 1893.

Conan Doyle also entered into correspondence with Stevenson and the latter wrote of his suspicion that Holmes was based on Stevenson’s friend and Conan Doyle’s medical professor at Edinburgh University, Joseph Bell.

This was subsequently verified by the man who brought the Baker Street detective to life.

Stevenson’s letters to Barrie show that he regularly returned to his homeland and enjoyed fishing in Highland waters on his travels.

Geese and turkeys

But he talks of one meeting with a pair of terrifying matriarchal characters in a scene which could have come straight from Maggie Smith in Downton Abbey.

As he related: “There came one day to lunch at the house two very formidable old ladies – or one very formidable and the other what you please – answering to the honoured and historic name of the Miss Carnegy Arbuthnotts of Balnamoon (which is situated seven miles east of Glenogil in Angus).

“At the table, I was exceedingly funny and I entertained the company with tales of geese and bubblyjocks (turkeys).

“I was great in the expression of my terror for these bipeds and suddenly, this horrid, severe and eminently matronly old lady put up a pair of gold eyeglasses, looked at me a while in silence, and pronounced her verdict.

“She said: ‘You give me very much the effect of a coward, Mr Stevenson. I had very nearly left two vices behind me at Glenogil: fishing and jesting at the table. And of one thing you may be very sure, my lips were no more opened at that meal’.”

Barrie and Stevenson left behind them an immortal body of work and unforgettable works of literature.

And it’s as if they have returned to life through the labours of Dr Shaw.

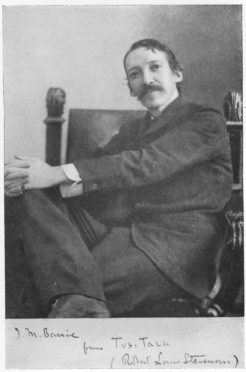

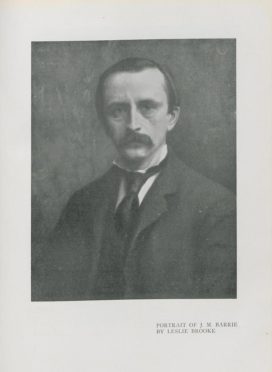

The two famous Scots who thrilled generations of readers

Sir James Matthew Barrie (1860-1937) was a Scottish novelist and playwright, best remembered as the creator of Peter Pan.

He was born and educated in Scotland and then moved to London, where he wrote a number of successful novels and plays.

There he met the Llewelyn Davies boys, who inspired him to write about a baby boy who has magical adventures in Kensington Gardens (first included in Barrie’s 1902 adult novel The Little White Bird), then to write Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up, a 1904 “fairy play” about an ageless boy and an ordinary girl named Wendy who have adventures in the fantasy setting of Neverland.

Barrie unofficially adopted the Davies boys following the deaths of their parents.

He was made a baronet by George V in 1913 and a member of the Order of Merit in the 1922 New Year Honours.

Before his death, he gave the rights to the Peter Pan works to Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in London, which continues to benefit from them.

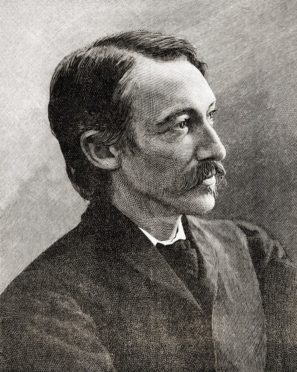

Stevenson

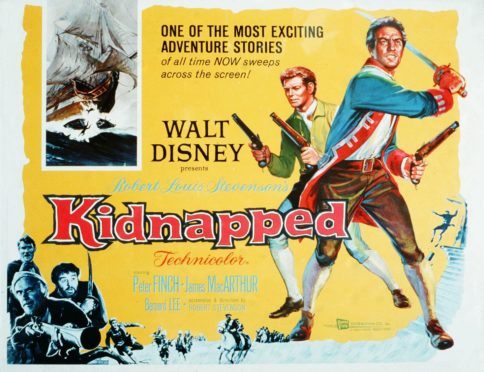

Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894) was a Scottish novelist, poet and travel writer, most noted for Treasure Island, Kidnapped, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and A Child’s Garden of Verses.

Born and educated in Edinburgh, Stevenson suffered from serious bronchial trouble for much of his life, but continued to write prolifically and travel widely in defiance of his poor health.

As a young man, he mixed in London literary circles, receiving encouragement from Andrew Lang, Edmund Gosse, Leslie Stephen and W E Henley, the last of whom may have provided the model for Long John Silver.

In 1890, he settled in Samoa where his writing turned away from romance and adventure toward a darker realism. He died at his island home in 1894.

A Friendship in Letters is published later this month by Sandstone Press.