When Moira Armstrong was growing up in the north-east of Scotland in the 1930s, she quickly realised how important the different aspects of local history, heritage and language were to the people around her.

She went swimming at Stonehaven’s art deco open air pool, learned to speak Doric, cycled from Aberdeen to such sites as Dunnottar Castle, took an interest in the advancing technology of television…and eventually became one of the most highly-regarded figures in the industry, directing a litany of award-winning programmes.

Indeed, her CV resembles a veritable Who’s Who of the great and the good of TV history, encompassing everything from Z Cars and Dr Finlay’s Casebook to Midsomer Murders, Marple, Lark Rise to Candleford, Softly Softly, The Bill, Play for Today, Peak Practice, The Onedin Line, Where the Heart Is and The Last Detective.

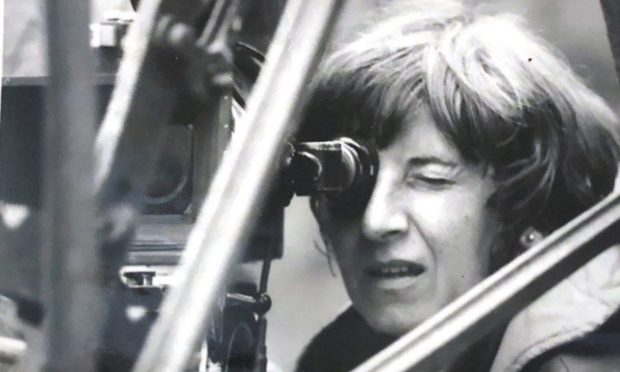

The Crieff-born Scot was also behind the camera lens for the groundbreaking BBC adaptation of the classic Lewis Grassic Gibbon novel Sunset Song, which was broadcast 50 years ago, and the award-winning Testament of Youth, which gained five Baftas, including one for herself and her colleague Jonathan Powell in 1980.

And she still derives immense satisfaction from being at the helm of the mid-70s series The Girls of Slender Means, based on the novella by Muriel Spark, which featured a near all-female cast, led by Patricia Hodge, Miriam Margolyes and Mary Tamm.

The early stages in Moira’s distinguished career

Moira has never been afraid of hard work and, even at 90, gives the impression she is temperamentally as fragile as a moose.

There weren’t many high-profile women involved in TV in the 1950s or 1960s, but the youngster, who was educated in Aberdeen before moving to Edinburgh University, had ample reserves of perseverance, patience, a talent for breathing life into her work, and parents who were happy to let her pursue her ambitions.

That was evident in the slightly faltering start to her career when her first acceptance letter from the BBC got lost in the post and her mother took matters in hand.

As Moira recalled: “She was so incensed that I hadn’t heard from the BBC that she went to Portland Place to the appointments department and complained about it.

“They said they had actually sent me a letter saying would I come for an appointment.”

Her first position with the corporation was in radio and she also trained as a continuity announcer before deciding to progress into television, initially moving to Thames Television as a directorial assistant.

The youngster soaked up knowledge like blotting paper and returned to the BBC for a directing course, which inspired her into a brave new world where she combined classic series with gritty, single-issue plays and couthy casebook tales with police procedurals.

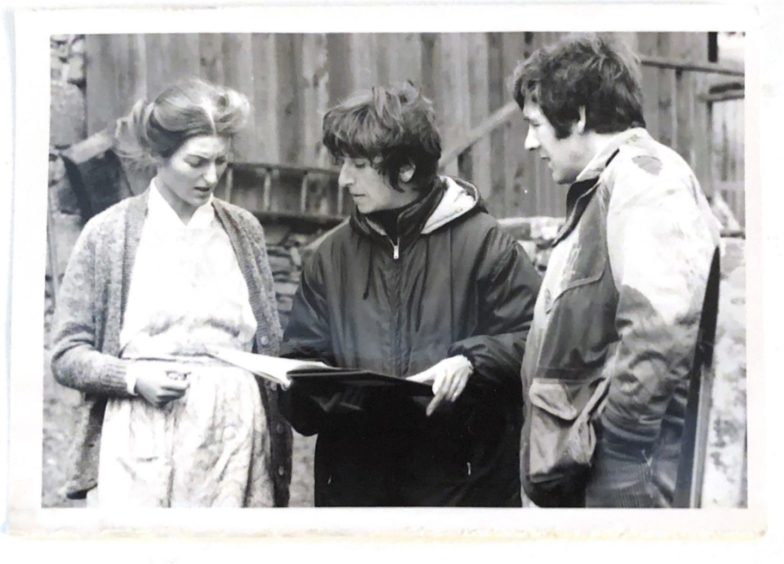

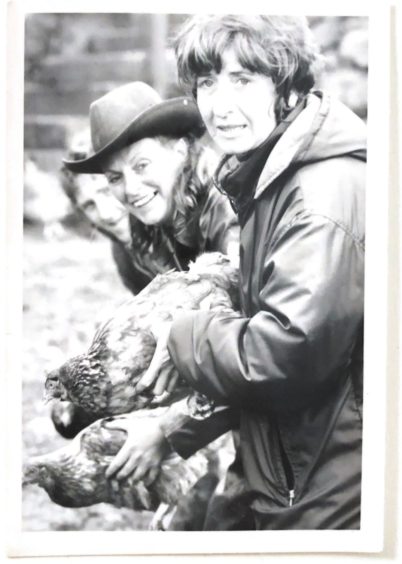

Sunset Song was shot all over the north-east

Her early years in the Granite City and her many trips to Aberdeenshire meant that she was an ideal candidate to transfer Sunset Song from page to screen.

But she was effusive about the job done by Bill Craig in creating a screenplay which crackled with the vim, vigour and vitality which was obvious in Grassic Gibbon’s work.

As she said: “I had read the book when I was a schoolgirl and it had an impact on me, as it did with so many others. But Bill’s script was so good and so full of life that it would have been difficult to make a bad film of it.

“It flowed along, we were given a very generous filming schedule, and the actors poured themselves into it.

“Vivien Heilbron had to learn the language of the book and I coached her in some of it, but once we were up in the Mearns, she soon got into her stride.

‘We had to avoid all the electricity pylons’

“The main challenge for us involved in producing and directing was finding a farmhouse where we could shoot a lot of scenes without having to deal with giant electricity pylons. Nowadays, it wouldn’t be a problem – you could just remove the pylons in post production – but that wasn’t the case in 1970.

“Eventually, we settled on a place in Auchenblae, which had a non-approach road and was close to a long stretch of woodland – and that turned out to be an ideal setting.

“I was interested by the challenges of filming on location, but it was wonderful to be involved in that series. Sunset Song has got a very good narrative through it with the central character of Chris Guthrie [Heilbron] being the narrator, it is based in a part of Scotland which is not terribly well known outside of Scotland and it was the place where I had grown up, so it was very much like going back to my roots.

“I’m delighted that so many people still remember it with so much affection.”

Bafta success was a testament to Cheryl Campbell

Moira has proved herself a versatile figure, somebody who is more interested in stories and characters than being limited to any one genre or formula.

She has collaborated with many of Britain’s leading acting talents, but few impressed her more than Cheryl Campbell, who depicted Testament of Youth’s protagonist, Vera Brittain, the real-life nurse and author whose world collapsed around her as, one by one, the young men in her circle were embroiled in the Great War.

It was a deeply poignant, evocative anthem to doomed youth and the way in which Campbell’s character both mourned and raged about the madness in the trenches. As Moira said: “Cheryl was playing somebody who was younger than she was, but she could be strong and she could make you weep and that was very powerful.

“The first time I met her, I knew that she was right for the role and she was absolutely convincing, just as Vivien had been in ‘Sunset Song’.

“The trouble was that, in these days, actresses in particular found it difficult to get any other work after they had excelled in one series. They were typecast and pigeonholed as only being suitable for some parts and not others.”

Muriel’s novel sparked a long-time friendship for Moira

Moira has spent recent months dealing with lockdown, but remains one of life’s irrepressible individuals, with trenchant views on everything from the Westminster government’s handling of the pandemic – “totally incompetent” – to why she is no longer involved in television direction – “I can’t get the insurance.”

She also wondered why, with broadcasters struggling to fill their schedules, the BBC hadn’t decided to repeat some of their best dramas from the 1970s and the 1980s.

One of her own favourites is The Girls of Slender Means which was shown in 1975 and gained a positive reception, not least for the way it interweaved the Scottish author’s waspish streak with a sense of loss: a prevailing theme in so many of the best literary works which, whether coincidentally or not, has struck with chord with Moira.

She said: “It was set in a girl’s club at the end of the Second World War and it has got tragedy, it has got humour and a very powerful human element, and yet the BBC keeps telling me it would be too expensive to show it again. And when you think how popular Miriam is these days….if you try to meet her in the street, she is always surrounded by people who recognise her from the Harry Potter movies.

“It was very enjoyable to film it with so many strong female characters involved and it’s a film which has had an enduring legacy, because Miriam, Patricia [Hodge], Mary [Tamm] and I still meet up every year and we have kept in touch.

“It’s obviously not possible for us to do that at the moment, and I know things are complicated for many people working in television. Plenty of films are still being made, but they tend to have more money and can afford to work around the social restrictions.

“As to what is going to happen in the future, who knows? Britain is way down the list in terms of doing well [in tackling Covid] and a lot of that is down to how the Government here [she lives in London] keeps changing its policies and getting caught out.

“You can’t be worried about being popular in these circumstances. You have to concentrate on what is best for the country, not on what might win you votes. In New Zealand, their prime minister [Jacinda Ardern] recognised the scale of the pandemic and imposed very stringent restrictions. It worked and now they are free of Covid.

” I hope we will be in the same position later this year, but I’m not overly confident. What has happened so far has been totally incompetent. You have to keep ahead of something like this and not be reacting to events all the time.”

The play’s the thing for Moira Armstrong

If you want an indication of the pioneering fashion which explains why Moira was the subject of a special BFI retrospective in 2014, just consider her involvement in so many different programmes during the course of the last six decades.

When the BBC screened a celebration of Play for Today late last year, it highlighted the depressing statistic that just 12 out of 300 works had been directed by women.

And five of these were filmed by the nonagenarian from the north-east who provided a pithy response to me telling her that she didn’t sound 90.

“What does 90 sound like? I think I sound pretty much the way I have always sounded.”

Cut!