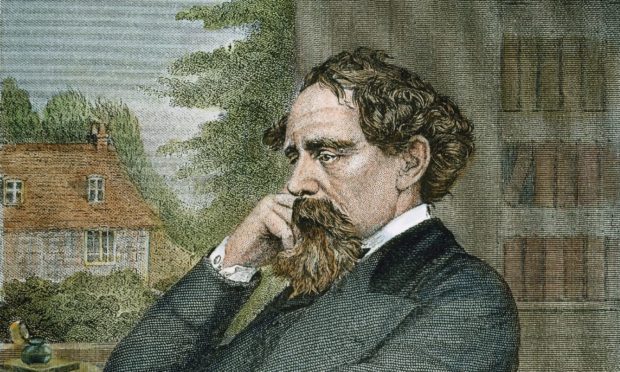

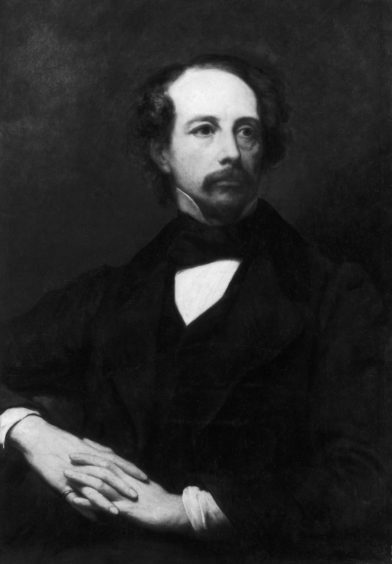

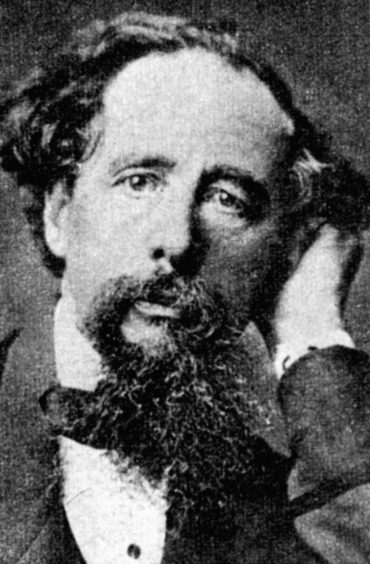

Charles Dickens is the author whose works and characters still resonate with audiences across the world more than 150 years after his death.

And his surname has even entered our dictionaries and phrasebooks, while a variety of his more renowned creations – such as Mr Micawber, Ebenezer Scrooge, Oliver Twist, Fagin and Uriah Heep – have become every inch as famous as his myriad classic novels, ranging from Bleak House, The Pickwick Papers and A Tale of Two Cities to David Copperfield, Hard Times and A Christmas Carol.

Dickens packed a remarkable amount into his 58 years. He was a voracious publisher, enthusiastic traveller, accomplished actor and versifier, and he approached his literary duties as if he was writing for a soap opera, often ending his chapters on a cliffhanger, as Victorian readers were left anxiously waiting to see what happened next.

A new film based on Dickens’ novel Oliver Twist is just out featuring an array of British actors including Sir Michael Caine, Rita Ora and David Walliams.

The plot has Oliver reinvented as a streetwise artist who is living on the streets of modern-day London and the release of the film gives us a chance to look at the Scottish links to Dickens.

Even though none of his most acclaimed offerings were based north of the Border, he regularly journeyed to Scotland, derived inspiration everywhere from Edinburgh to Aberdeen and the Highlands, and spoke warmly about the people and places he met.

An Edinburgh gravestone gave us an immortal figure

He’s one of the most memorable characters in the whole history of literature.

And Dickens, who was always a lover of unusual and striking names, must have thought all his Yuletide carols had arrived at once when he came across a singular gravestone in Edinburgh’s Canongate Kirkyard.

There it was, the memorial to “Ebenezer Lennox Scroggie – the cousin of the economist Adam Smith, who was known as a carousing, often scandalous figure in high society.

The epitaph listed Scoggie’s profession as a “meal man”, but Dickens misread this as “mean man” and the idea for a new novel sprung into his head.

All it required was a slight alteration from “Scroggie” to “Scrooge” and the scene had been set for a man who has been portrayed by everybody from Alastair Sim and Michael Caine – with The Muppets – to Patrick Stewart and George C Scott.

The author made a lengthy visit to the north of Scotland in 1841 and was thrilled by the beauty and rugged surroundings in which he immersed himself.

Above all, he was captivated and horrified by the stillness which pervaded Glencoe, even as his guide, Arthur Fletcher, told him about the site’s notorious massacre.

On Monday July 5, Dickens wrote about his varied experiences while touring through the Trossachs and thereafter venturing further north on the group’s hectic schedule.

Reigning supreme in Scotland’s unique rain

He said: “We left Edinburgh yesterday morning at half past seven and travelled, with Fletcher for our guide, to a place called Stewart’s Hotel, nine miles further than Callander. Being very tired (for we had not had more than three hours sleep on the previous night), we lay till ten this morning and then, at half past eleven, we went through the Trossachs to Loch Katrine.

“I walked from the hotel after tea last night. It is impossible to say what a glorious scene it was. It rained as it never does rain anywhere but here, but that was of no import.

“I won’t bore you with accounts of Ben this and lochs of all sorts of names, but this is a truly wonderful region.

“The way that the mists were stalking about today, and the clouds lying down upon the hills, the deep glens, the high rocks, the rushing waterfalls and the roaring rivers down in deep gulfs below, were all stupendous.

“[However], Glencoe was perfectly terrible….it was an awful place. If you should happen to have your hat on, take it off, so that your hair may stand on end.”

A double date of drama in Aberdeen

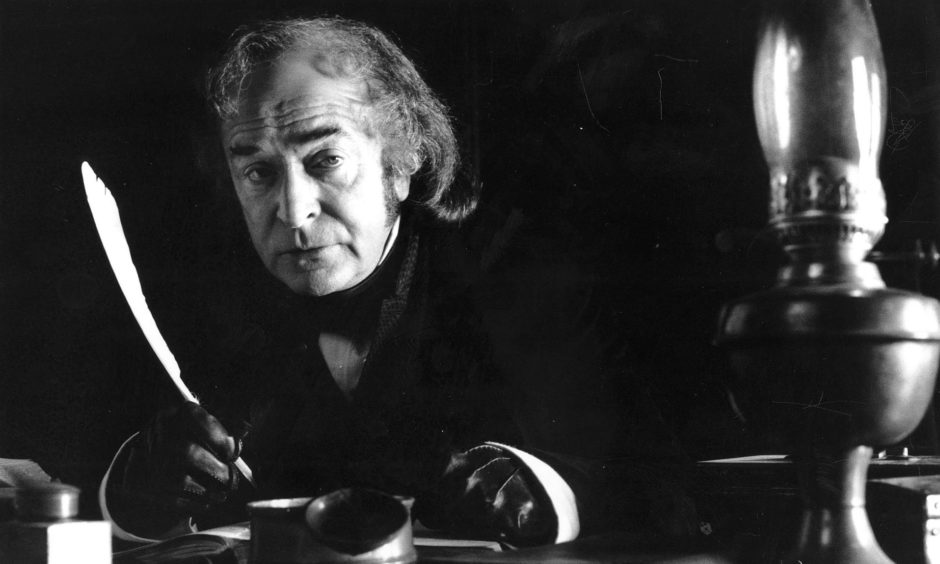

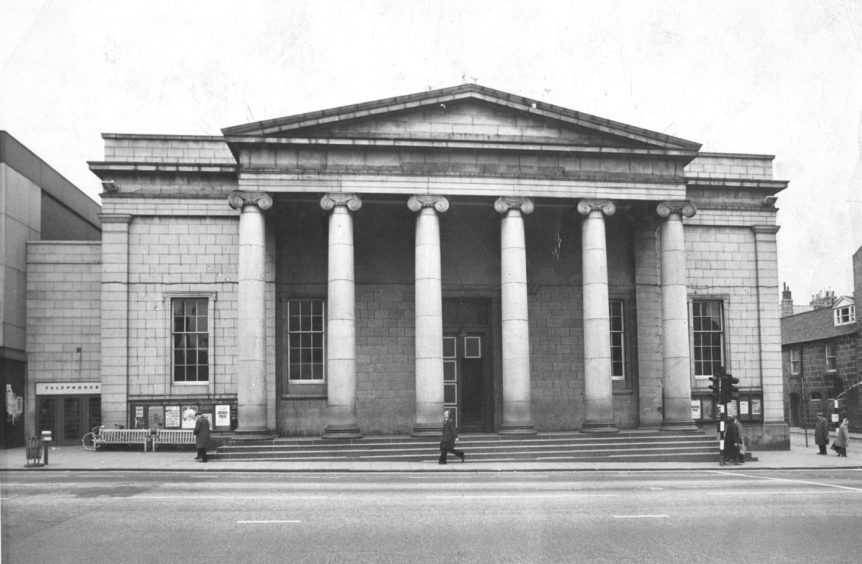

Dickens was a little coiled spring of energy whenever he was offered the chance to perform on stage. And he delighted Aberdeen cultural aficionados on two occasions at the fabled Music Hall in 1858 and 1866.

On the first occasion, he was in the midst of a tempestuous time in his personal life. A few months earlier, his 22-year marriage had come to an acrimonious end after he fell in love with a young actress, Ellen Ternan.

The contemporary newspapers were scathing about his conduct and there were moral objections to his visit. One irate member of the public wrote to the Aberdeen Journal, deriding the author’s conduct in backing entertainment events on Sundays.

But the noted Dickens expert, Dr Paul Schlicke, who has championed the writer for many years at Aberdeen University, explained that the show was a major success.

He said: “The visit went very well and there were adulatory reviews in the Free Press and the Aberdeen Herald.

“The Aberdeen Journal’s man sniffed that a visit of less than 24 hours was ‘a short time to spend in our fair city’, but he soon changed his mind.

“He wrote: ‘We had not long listened to him when we felt that the creations of his fancy fathered tenfold vigour from his representation….and he brought many of his characters to vigorous, thrilling life in his embodiment.”

A last hurrah and a dose of Granite noir

His second appearance came when the writer was 54 and in poor health, suffering from a bad cold and pain in his eye and hand.

He travelled to Scotland by train with his manager, George Dolby, in this instance to deliver just a single reading, and seemed weary on his arrival at the railway station.

And yet, how he transformed himself during the gruelling two-hour performance, which included a dramatic rendition of the deadly storm passage from David Copperfield and a recitation of the comedic trial scene in The Pickwick Papers.

The audience were enthralled and, despite Dickens’ afflictions, he rallied himself sufficiently to regale the crowd with a stirring sailor’s hornpipe.

The Aberdeen Journal raved about what they had just witnessed.

The paper’s critic said: “The great novelist, though turning over in years, retains all the fire and energy of expression and all the juvenility and vigour of spirit which is necessary to provide a true and vivid depiction of the best creations of his genius.”

It was typical of Dickens that he rose to the occasion, regardless of any personal considerations. He eventually ceased to embark on these individual shows, recognising that he was no longer fit enough to put his body through the wringer.

He died in June 1870, but left behind a treasure trove of literary marvels.