On February 25 we said goodbye to a visionary scientist whose pioneering work as the head of a small Aberdeen team changed the face of medical science as we know it.

Professor John Mallard passed away at the age of 94 but left behind him a legacy which still benefits millions of patients all around the world.

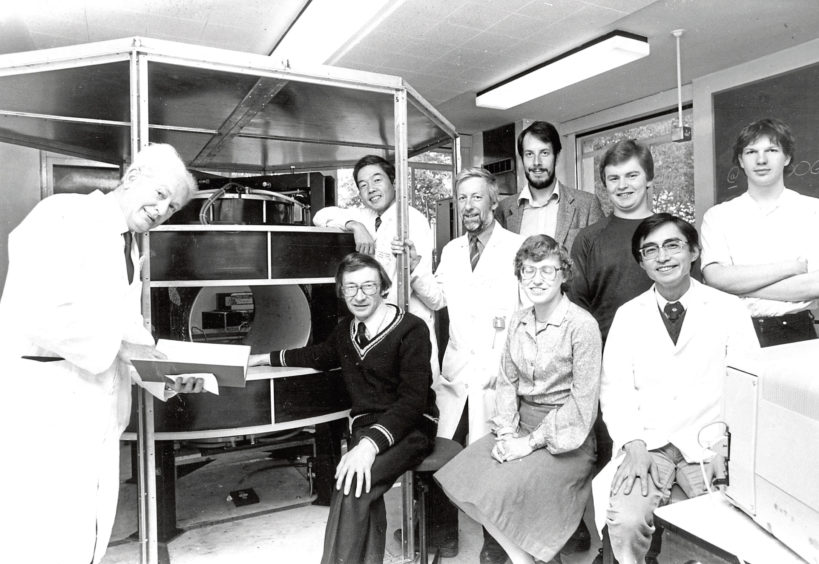

Under his leadership, a small team – who he would later describe as “half-mad scientists” – built the world’s first whole-body MRI scanner and successfully demonstrated its clinical value.

But his was not a story of huge resource and big financial backing. It was Mallard’s leadership, tenacity and can-do approach that drove a scientific breakthrough still pivotal to medical treatment today.

Professor Mallard saw the ‘big picture’ before anyone else

His Aberdeen story began in 1965 when he relocated to the city from London to become the University’s first Chair of Medical physics. He began to assemble a team, appointing Jim Hutchison to work on a project exploring the possible medical uses of magnetic resonance.

Following up on two seminal American studies, demonstrating that magnetic resonance could distinguish between normal and cancerous tissue and could be used to produce images, Mallard and Hutchison set about bringing these two elements together.

By 1974 they had obtained the first ever MRI picture of a mouse using a homebuilt benchtop scanner, although it took an hour to produce the image.

Mallard immediately saw the ‘big picture’ and while other research teams around the world built machines that could image parts of the body, the Aberdeen team focused on building one capable of whole-body human images. But convincing funders to back his ideas proved a battle and after many trips between Aberdeen and London, he eventually persuaded the Medical Research Council to support their endeavours.

The researchers, who by this time had involved chief technician Eddie Stevenson from the Medical Physics workshop, then set about design and construction.

The eureka moment

The Mark-1 scanner they created was put together on a shoestring budget of just £30,000, which also had to stretch to cover the staff time.

Hutchison had designed the magnet but using this to create a full-body MRI scanner required great ingenuity.

It arrived without a cooling system and after running it for an hour, became so hot that it could fry an egg. A cooling system was designed but leaks meant the team spent a huge amount of time dealing with dripping water.

Mallard later said that it still “made him weep” to think of how the technology was shunned here for so long

They also required large radio-frequency coils but, with funds limited, they turned to materials they could access easily and so central heating pipes and even a tube from a children’s play park were utilised.

Mallard’s team made much progress but were still unable to reconstruct images which were diagnostically useful.

Their eureka moment came when American scientist Bill Edelstein joined their ranks. By combining expertise, they developed the spin-warp imaging pulse sequence – a method which overcame previous difficulties in ‘freezing’ images of naturally moving parts of the body.

They put their theory to the test and, late at night in April 1980, captured world-first whole-body MRI images.

Thank Professor Mallard for life-saving technology

After becoming their own guinea pigs by scanning themselves multiple times to ensure there were no ill effects, in August 1980 the team were ready to scan their first patient – a Fraserburgh man known to have multiple tumours.

The images obtained by their Mark-1 scanner showed up clear differences in his liver and spleen and also identified a previously unknown tumour in his spine.

As soon as the success of the machine had been demonstrated, a steady stream of patients was brought over from Aberdeen Royal Infirmary. It was so popular that they could no longer access it for research and so they sought funds for a Mark-2 scanner but were unsuccessful in the UK. Funding was eventually obtained from a Japanese company in exchange for know-how.

It took until the 1990s for MRI to become widespread in the NHS. Mallard later said that it still “made him weep” to think of how the technology was shunned here for so long.

Mallard also continued to champion other advances in imaging technology, including the development of positron emission tomography (PET). Today the state of the art Scottish PET Centre at ARI bears his name.

So next time someone you know is referred for an MRI scan, remember that it was the pioneering work of Mallard and his Aberdeen team that made this life-saving technology possible.

Emeritus Professor Peter Sharp worked for MRI pioneer Professor John Mallard and then became his successor