Throughout my career in diabetes research, insulin was always available and for those with Type 1 diabetes it is a truly life-saving treatment.

But for too long the major contribution of Aberdeen-educated John JR Macleod to the discovery of insulin has been largely unknown.

A headstone in Allenvale Cemetery proclaims him as “Co-Discoverer of Insulin”, while a commemorative plaque in Cairn Road, Cults announces him as “co-discover of insulin and Nobel prize winner” who once lived there. Yet few have heard his name.

Celebration of the man and his work has been muted – perhaps in part due to the natural reticence of the “north-east condition” – but more likely resulting from the popular myth of the insulin discovery and attendant claims that Macleod’s recognition by the Nobel Prize Committee was undeserved.

In 2021, the world is celebrating the centenary of the discovery of insulin somewhat prematurely, following the traditional narrative that plaudits are owed only to two inexperienced Canadian researchers, Frederick Banting and Charles Best.

As is apparent on examination of the facts, the true centenary of the magnificent Toronto breakthrough comes next January and Macleod was undoubtedly a central figure. It is time for all Aberdonians to know his name and understand his greatness.

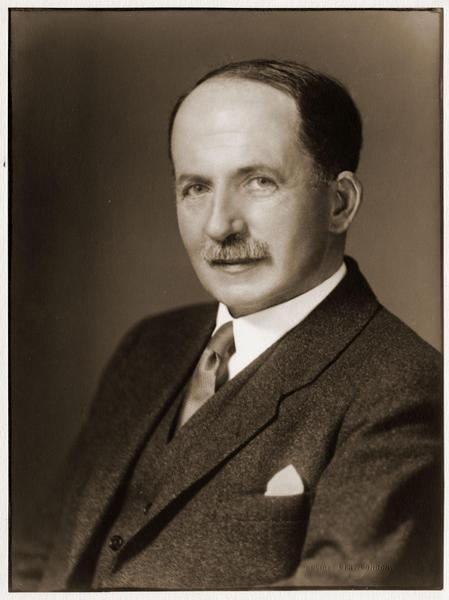

Who was John JR Macleod?

Born near Dunkeld, Macleod moved to Aberdeen when his clergyman father was appointed to a city church. A prize-winning grammar school pupil, he similarly excelled in medicine at the University of Aberdeen.

On graduation he won a travelling scholarship to Leipzig where he embarked on a career in physiology. After time in London, he became a professor of physiology in Cleveland, Ohio aged only 27. Fifteen years later, this successful researcher and talented teacher was recruited by the ambitious University of Toronto.

When young Canadian doctor Frederick Banting, with no experience of diabetes or research, came up with an idea to find a treatment for the condition, he was directed to Macleod – a famous authority on carbohydrate metabolism. Macleod generously offered laboratory space and guidance to the inexperienced Banting, plus a student assistant, Charles Best.

Macleod was quiet, methodical and rigorous in his work. Banting was driven, impatient and not well read. This disparity led to clashes which would damage their professional relationship and Macleod’s historical legacy.

The Toronto breakthrough

Banting’s and Best’s early experiments were mostly conducted while Macleod was back in Scotland. When they wrote to tell him of promising results, he urged caution advising more careful repetition of experiments to avoid misinterpreting results.

Banting’s fury at what he perceived as rejection of his findings fuelled irreversible growing resentment.

Having prepared a pancreatic extract that variably lowered blood sugar in diabetic dogs, Banting and Best had got about as far as several earlier groups. While Banting was permanently convinced he had already discovered the “cure”, this view was never tenable as his “big idea” proved unnecessarily complicated and was completely abandoned. Furthermore, nobody thus far had made extract sufficiently pure for continuing human usage.

Macleod’s experience guided the research to completion in both producing usable insulin and characterising its physiological properties

Macleod’s experience guided the research to completion in both producing usable insulin and characterising its physiological properties. The definitive progress came when visiting biochemistry professor, James Bertram Collip, joined the team in December to apply his expertise on extracts of whole bovine pancreas.

Banting, threatened by Collip’s progress, saw a human trial of his own extract fail in early January. However, by January 23 1922, Collip’s purer extract had spectacular, life-saving effects on young Leonard Thompson. This was the Toronto breakthrough.

Time to restore Macleod’s unfairly diminished reputation

The confusion around the centenary date symbolises a steady erosion of Macleod’s place in the great discovery. In 1923, Macleod and Banting shared a Nobel Prize, but Banting and his allies told anyone who would listen that Macleod had no right to any credit, having simply stolen Banting’s (abandoned) idea.

The successful campaign in Canada to have Banting lauded as the main discoverer saw further distortions after his death, when Best progressively claimed that he deserved most of the credit.

As we approach the (real) 100th anniversary of this remarkable breakthrough, it is now time that Macleod’s deserved glory is appreciated more widely

Not until 1982 – when Toronto historian Professor Michael Bliss returned to original laboratory notes and files to produce his definitive work, The Discovery of Insulin – was there serious recognition of the burning need to restore Macleod’s unfairly diminished reputation.

Local attempts thus far include the 1993 biography published by Aberdeen diabetologist, Dr Michael Williams, and the opening of the JJR Macleod Diabetes Centre at Foresterhill by Professor Bliss in 2013.

As we approach the (real) 100th anniversary of this remarkable breakthrough, it is now time that Macleod’s deserved glory is appreciated more widely.

Retired diabetologist Ken McHardy is an honorary senior lecturer at the University of Aberdeen who spent more than 30 years working in diabetes with NHS Grampian