A team from Aberdeen University has made a discovery in an ancient Scottish loch that could alter science’s understanding of evolution.

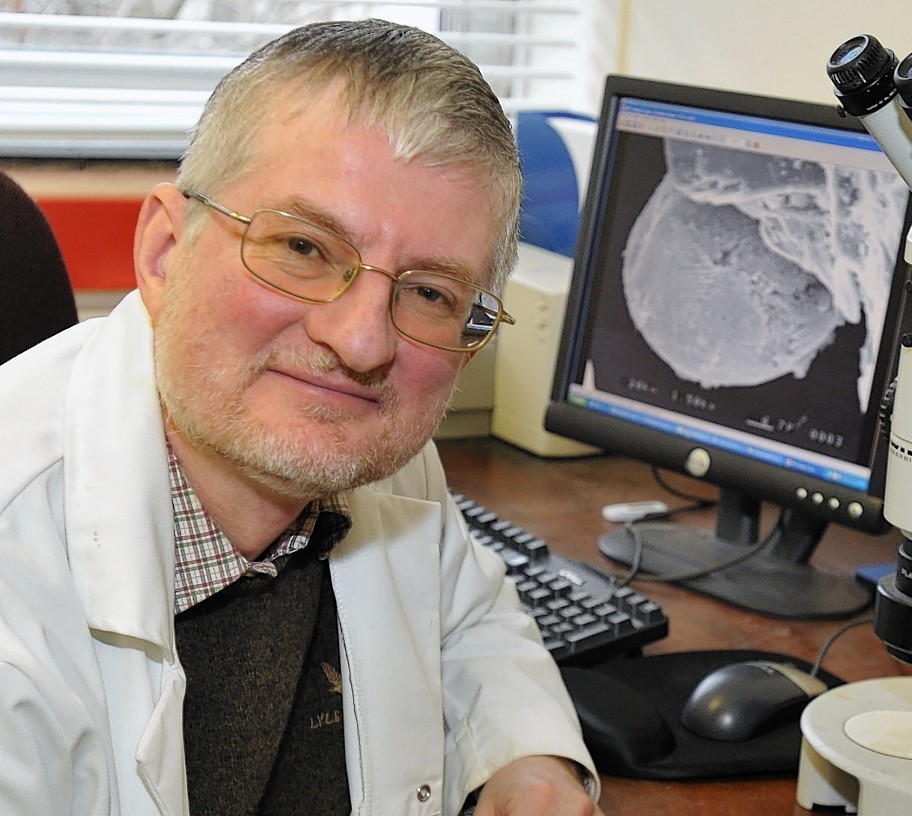

Scientists from the institution’s school of geo-sciences have been studying ancient sediment deposited in the Bay of Stoer in north-west Scotland more than 1.5 billion years ago.

During their investigation, they discovered high levels of the metal molybdenum, a key element in the evolution of multicellular life.

Their discovery could shake a few branches on the evolutionary tree, as it challenges the commonly held view that complex lifeforms first evolved in the ocean depths, and instead developed on dry land.

Professor John Parnell, from the research team, said: “The discovery bolsters up a developing theme, which is that continents were at least as important as the oceans for evolution, and what we have done is contribute some new information which makes this theory more likely.

“We’re very fortunate in Scotland because we have some very well-preserved rocks that were laid down in a lake about 1.5 billion years ago, and when we analysed them chemically we found an amount of a very particular trace element which is very important in this evolutionary stage.

“The amount of this element, molybdenum, which is in these rocks, was much greater than what was in the oceans at that time. So the fact that it was available on land more than it was in the oceans suggests that this major step did in fact take place on land.

“When carrying out this kind of research there are very few rocks that you can study that have been deposited in a terrestrial setting, which is what makes this site in north-west Scotland special.”

The research team’s finding were published in the journal Nature Communications yesterday.

Prof Parnell added: “This research is part of a bigger body of work on these rocks which is ongoing. It is clear that the site is a very important archive to help us understand the earth’s early history, so we will continue to develop that work at Aberdeen.”