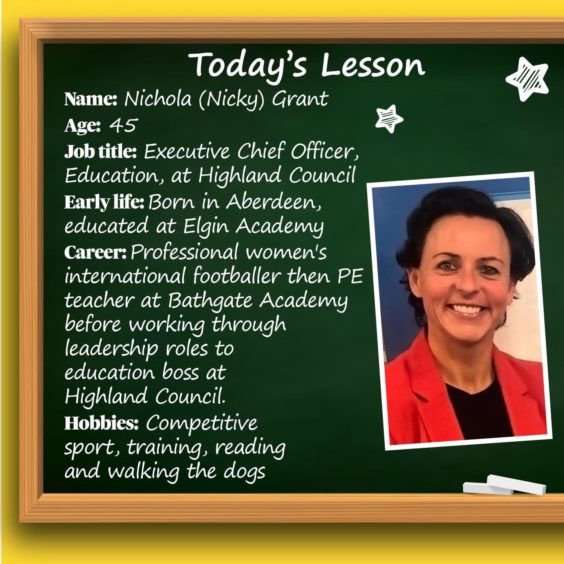

Nicky Grant is driven by results. The ex-football international turned Highland education boss has dedicated her career to delivering strong performances through team work.

It’s a personality trait as much as a professional skillset, and one that emerged at a young age. “At school I excelled in competitive sport,” she says. “I played badminton, hockey and football, and played my first Scotland match at 14. My school hired two buses to go down and celebrate.”

It was this unwavering support that, some 26 years later, would bring Nicky home to Elgin High School – this time as deputy head teacher.

Many of the teachers who taught Nicky were still in post, and they pushed her to champion the next generation coming up through the school. Today, Nicky describes it as the best thing she’s ever done.

It’s been quite a career trajectory. Nicky was formally appointed Executive Chief Officer for Education at Highland Council in June, after holding the position on an interim basis throughout the pandemic.

Now with her feet firmly under the table, she has once again got her eyes trained on the goal.

“Go home and trust in us”

Unsurprisingly, achievement is a key focus for the education service. Nicky was originally hired as the interim head of service, and the council was clear in its expectations. “The big thing was to drive attainment,” says Nicky. “The council wanted vision and transformation.”

What the council hadn’t banked on, of course, was the outbreak of a pandemic. Overnight the priorities changed. It was a strange time to take the reins.

“I found myself effectively having to tell teachers ‘You have 24 hours, gather what you can, go home and trust in me and the directorate,'” Nicky recalls.

What followed was an almost military-style operation. “I had to quickly assess the team and their strengths,” says Nicky. “Officers were then assigned tasks such as day-to-day communication with schools and unravelling and communicating the government information that was flowing in constantly.

“One of the biggest challenges was managing our expectations. I still had a vision I wanted to take forward but I had to be patient and manage the pace of change. However, my glass is always half full so I saw a lot of positives during Covid. There were things we could have done better but there were also so many green shoots.”

Young people are resilient

These green shoots were strengthened partnership working between members, officers, schools and parents, and a massive upskilling in digital learning. Most of all though, it was the sheer resilience of the teachers and pupils themselves. Nicky recalls one particular incident that struck a chord.

“During lockdown I joined some of the schools’ meetings and popped in and out of classrooms,” she says. “On one occasion I watched a headteacher deliver the school assembly to her own two children at home, with the rest of the class joining in online. I’m so proud of the creativity of our schools.

“Every time I joined a meeting in that period, I saw the strength, courage and confidence with which the young people adapted to blended learning. We talk a lot about recovery but it’s worth remembering that young people are very resilient.”

This resilience is something Nicky has sought to champion throughout her career. She has a particular interest in closing the attainment gap for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Football star

Nicky herself had what she describes as a “working class” upbringing, living in a traditional two-up-two-down council house. “I had lots of love and support at home and at school,” she says. “My PE teachers in particular took the time to understand where I came from, what my dreams were.

“I always wanted to be a footballer but Mum and Dad instilled me with values to have an education first, so I did my four year degree in education and played semi-professional football throughout my time at university.”

After graduating, Nicky turned professional, amassing over 90 appearances for the Scottish women’s national football team.

Football took her all around the world, to Iceland, Amsterdam, Sweden and Germany, before a ruptured Achilles and cruciate forced her to make a change.

“I suffered two career-threatening injuries, and if I can’t do something to the best of my ability I won’t do it,” says Nicky. “I wanted to give something back, so I returned to teaching.”

Proud moment

Nicky took up post as a PE teacher at a deprived school in Bathgate, where she found she could make a difference by telling her story. She spent the next few years climbing the ladder to a position as deputy headteacher, before returning to Elgin as deputy head. From there, Nicky secured her first headteacher post, at Alness High School.

“I always do my research on a school,” she says. “Like Elgin, it was a vulnerable area with high deprivation, and the school had come through four years of poor inspections. I saw the lack of confidence in the staff and young people and believed I could make a difference.

“I’m interested in performance and attainment. We were due another inspection in three months and the whole school galvanised around that goal. We came through it with flying colours. It was one of the proudest moments of my career.”

Assessment double stress for teachers

That attainment focus is at the heart of the vision for Highland education. However it’s coupled with a renewed emphasis on wellbeing.

“I gave three priorities to schools during Covid,” says the Highland education boss. “The first was wellbeing, because if we get that right we boost achievement for everybody. Then it was literacy and numeracy. Thirdly, outdoor learning. We’ve supported our schools and worked with partners to focus on those three key things.”

There are already some early improvements in attainment, especially for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds. While adopting the new approach to exams (called the Alternative Certification Model) was a “double stress” for teachers during lockdown, the council gave schools a level of flexibility in meeting the unique needs of their learners.

For example, pupils’ results were submitted as late as possible to maximise their chances of getting an award. Pupils were also given the chance to sit an exam if the teacher felt a ‘no award’ was likely based on classwork. Some schools delivered the curriculum right up until the summer holidays, while others started the assessment process earlier. “We did the right thing, as schools know their young people the best,” says Nicky.

This year’s results show what Nicky calls a “steady improvement” as well as a 3% improvement for the most vulnerable pupils. Some 92% of this group sat their assessments in 2021, compared to 85.7% in 2019. “It’s to their credit,” says Nicky. “I admire young people for the way they have gone through everything – self-isolation, studying at home – and shown so much resilience. The schools did amazing piecing that together too.”

First in Scotland

Nicky believes that the key to narrowing the attainment gap is to focus on the background of each child. “We need to take the individual into consideration, and our guidance staff are brilliant at that,” she says. “It’s thinking about where they’ve come from, their socio-economic background in particular, and finding positive pathways.”

This emphasis on positive pathways has led Highland Council to a first in Scotland. It has recently hired a dedicated officer who will act as strategic lead for employability and prosperity. They will work with elected members, officers across the council, communities and colleges to develop positive destinations including foundation and modern apprenticeships.

“It’s about the equity agenda, ensuring young people all have access to the same opportunities,” says Nicky. “The officer will work with Scottish Attainment Challenge schools and focus particularly on fourth and fifth year students on the brink of leaving with no positive destinations. We’ll involve families in that conversation too because that’s so important. It’s a really exciting role. No other local authority is doing this.”

Privileged position

This level of partnership working has to a great extent been a product of Covid – one of the green shoots Nicky is keen to nurture. As the new education boss she is full of praise for the support she has received since she started as head of service, in those strangest of times.

“The education service has had three directors and three heads of service in three years, yet staff have embraced change and bought into the vision,” she says. “There’s been that high quality leadership and empowerment agenda from the start. The officers continue to surprise me with their commitment to the service. At the same time, they’re always talking to me about what the future of education looks like. There’s a focus on the horizon.”

Yet the Highland education boss has not forgotten her beginnings as a 14-year-old footballer. She remembers the teachers who inspired her to push forward, and wants to remove barriers for women in sport and for young people whatever their background. That sense of achievement is the cornerstone of education, and it’s something Nicky does not take lightly.

“Yesterday, I wrote a letter to all staff – that’s 203 headteachers and 32,000 young people,” she says. “I wanted to tell them that I have such a privileged position to get to lead them into the future of education.”

More from Schools & Family

Shetland education puts children in the driver’s seat

Online safety – Why you should scrap the back to school mobile phone, and other tips