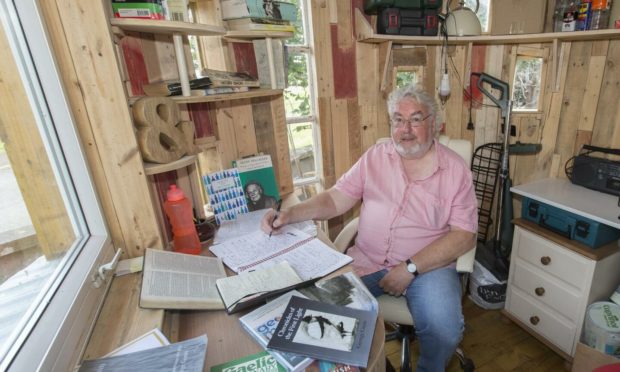

George Gunn asks me if I have a bag he can borrow. Any bag will do, it’s just for his notebooks as he heads off towards the Bervie Braes and Dunnottar Castle.

I grab him a cotton tote from our kitchen with the slogan “Hello Student!” and show him where the steep path begins up the cliff-side.

It’s early on a Sunday and the sun is already making its presence known, steam rising from the harbour beach.

We pass some tourists absorbed in their phones and George hitches the bag higher, the sound of pencils and paper making a satisfying clatter in the still morning air.

He is, from the top of his straw hat to the toes of his sturdy shoes, a writer, and a prolific one at that.

A respected poet and well-known playwright, George has more than 50 productions for stage and radio under his belt.

Add to that his book about Caithness, The Province of the Cat; his novel, The Great Edge, and seven collections of poetry.

Generating creativity

The Caithness Makar is in Stonehaven for the Wee Gatherin’ poetry festival and to read from his latest collection, Chronicles of The First Light, having endured a disrupted train journey from Thurso, which had taken up most of the previous day.

It’s been a busy week as he’s also been making a film with Lyth Arts Centre, where he is an artist in residence.

“It’s the only cultural hub we have in Caithness and it sits right in the middle of the county,” he says.

“It generates creativity by providing residencies for local and visiting artists of all disciplines and reaches out to schools and the broader community of the far north.

“It was set up in 1970s by Willie Wilson, an inspirational and idiosyncratic character.

“Lyth was originally a primary school and he bought it and slowly turned it into what it is now.

“Willie ran it single-handedly for 30 years, building an audience as he went along. He is the classic example of a man with a vision who just followed his instincts and interests and was determined.

“I knew his family very well. His auntie used to teach me drawing and painting at Dunnet Primary and his uncle used to take me fishing.”

Bringing culture together

George has been developing Words on the Wind, a poetry and film portrait of Caithness “as seen through the eyes and words of the people who live here”.

“Caithness is a poetic and a dramatic landscape and it lends itself to cinema,” he says. “Our culture, historically, is a bardic culture so all I am doing is bringing all these things together.”

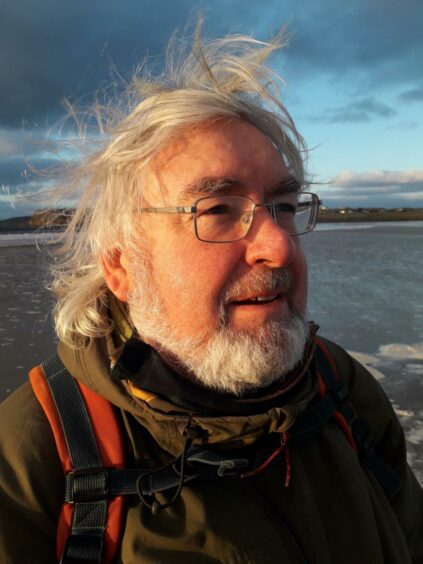

George was born in Thurso in 1956 and now lives there with his wife Christine.

“I grew up in the village of Dunnet with its beautiful beach at the foot of Dunnet Head. My mother was the district nurse and my father had a binder and then a combine so he cut the crofters’ crops.

“I’ve been writing all my life. My mother used to read to myself and my brother from abridged tales from The Iliad and The Odyssey and from Norse myths that my uncle George would send her.

“The same uncle used to take me to the Traverse Theatre when we went to Edinburgh on our holidays.

“I saw all sorts of stuff very young that I had no clue about but I loved it, and that love of theatre has remained with me.

“A play is a story told in public. The theatre is the last place where we are free to speak. All my plays start with an idea. It could be some great historical event like the Highland Potato Famine or the Clearances or a woman wearing a hat crossing a road.”

‘I will stop when I die’

George has two plays in the pipeline; Call Me Mister Bullfinch is a Royal Lyceum commission, and The Fallen Angels of The Moine will be toured by Dogstar Theatre “once Creative Scotland see sense”.

Of his other writing passion he said: “Poetry to me is like breathing. I’ve always done it and when I stop I will die.

“Chronicles of The First Light is the latest set of lyrical witnessing, because that’s what poets are, they witness, they chronicle, they report back to the collective.”

George’s second novel, The Vinegar Wind, will be published next year. Set in 1848 it takes place mainly on Dunnet beach and “is about famine and revolution, love and murder”.

After leaving school at 16 George spent two years deep-sea trawling out of Aberdeen then seven years working in the drilling industry in the North Sea.

“Everything is material,” he says. “I got to learn about the sea and I learned about the environment by being complicit in its destruction. I met people from all over the world and that was an education in itself.

“As a poet you walk through the world with your heart open and your eyes wide open. But you have to be tough or you will not survive.”