As animation fans flock to see Shaun The Sheep on the big screen, we take a peek behind the scenes at Aardman Studios. We won’t bleat on about it, but it was rather good…

Boxes of miniature mouths are poking out of a drawer. Over in the corner, a minuscule bottle of wine is delicately squeezed into place on a tiny restaurant shelf, while in another room hangs a startling photo collage of people with mullet hairdos, glaring into the distance.

This is Aardman Studios, home of Wallace & Gromit, Chicken Run and now Shaun The Sheep The Movie. And while the exterior of the building, situated on an industrial estate on the outskirts of Bristol and described by Aardman co-founder Peter Lord as the “grey box”, is clinically ho-hum, it belies the magic inside.

We were lucky enough to be invited in for a glimpse, and meet some of the 100-strong team grafting away on bringing Shaun The Sheep to the big screen. Like all Aardman films, the movie is an easy-to-love tale. Fed up with the hard work involved with being a sheep at Mossy Bottom Farm, under the nominal supervision of Farmer and Bitzer, his well-meaning but ineffectual sheepdog, Shaun decides to give himself a day off.

Events rapidly escalate out of control though, and Shaun’s mischief inadvertently leads to the hapless Farmer being taken away from the farm.

Having been crowned the nation’s favourite children’s character by a Radio Times poll, there’s plenty of appetite to see the fleecy one on screen.

“It was a fantastic honour,” says Richard Starzak, better known as ‘Golly’, who, along with Mark Burton, wrote and directed the movie and “effectively devised” the CBeebies series based on the character.

“Children love the idea of the sheep getting one over on the farmer,” adds Burton. “There’s a little metaphor there, of the children getting one over on adults. I think they love that sense of mischief.”

With the kids’ TV series shown in 170 countries, and boasting over five million friends of Facebook, Shaun, who first appeared in Wallace & Gromit short A Close Shave, is long overdue his own film.

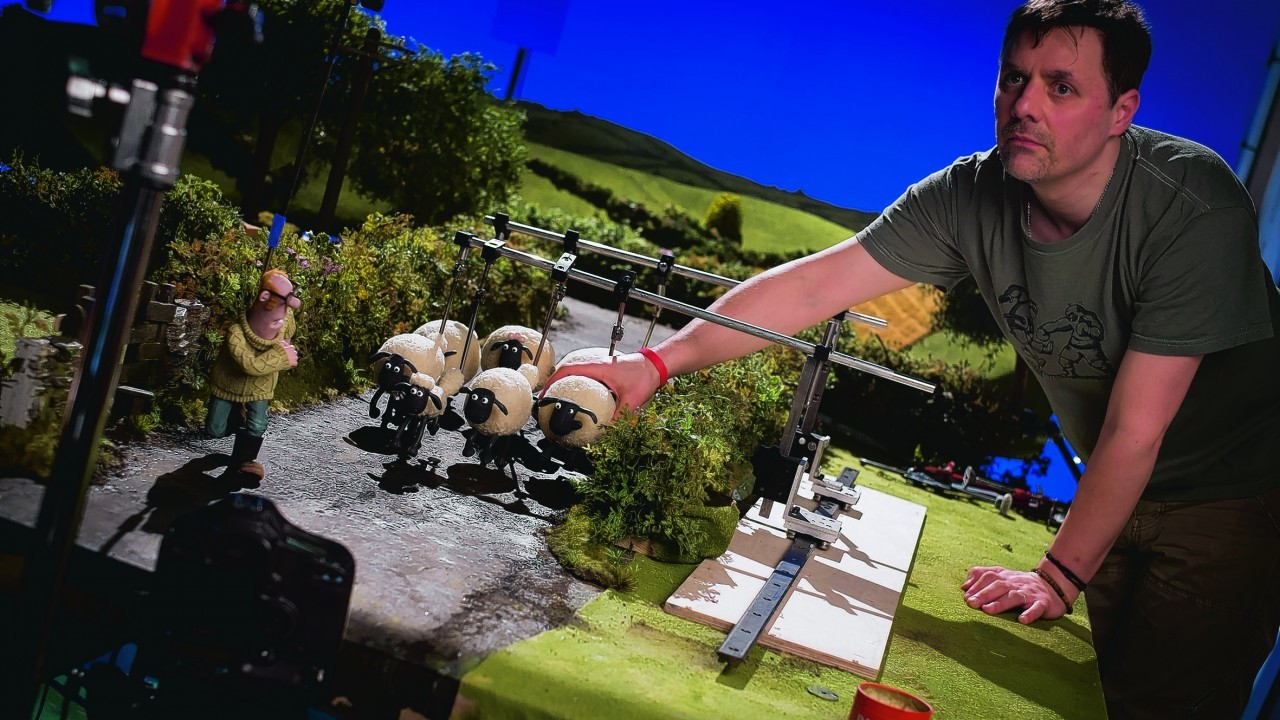

Taking into account that each animator produces an average of two seconds’ worth of footage every day, doing things the long way is the only way with stop animation.

“It’s taken three years to make the film,” explains Burton. “It’s hard work, but it’s fantastic.”

Between them, Golly and Burton look after 20 units, where the 17 full-time animators could be tasked with anything from re-fleecing one of the flock, laying out teeny tablecloths at model restaurants, or papering the wall of a miniature train station with a poster advertising a restorative cup of Gulpa Coffee – or perhaps a tempting new phone deal from Sir Chat A Lot.

But even seemingly small decisions take a long time when you’re working with plasticine.

“When you design a character, the clothes they’re wearing matter quite a bit, because if they change clothes, you generally have to re-sculpt them,” explains producer Julie Lockhart.

To keep the models and the animators’ hands clean, there are stacks of baby wipes everywhere: “They’re the best for getting off plasticine,” explains one modeller, as she selects a new mouth for a passer-by in one of the film’s scenes.

Just as important is ensuring everyone is reading from the same hymn sheet, so to speak. And considering it took five months to build the restaurant, which will be on-screen for around five or six minutes, there’s little room for costly error.

To avoid this, Golly and Burton act out scenes in front of a camera. Useful as this is, especially in “finding those little bits of magic, the things you can’t talk through”, it does mean they find certain models end up bearing a resemblance to them.

“The farmer’s Golly,” says Burton, laughing.

“Your own body language is so strong, it comes through. On a Friday evening, the crew gets together for a beer, and usually the editors find the most embarrassing things we’ve had to do throughout the week,” he adds.

“So we have to watch ourselves snogging, bending over, showing our backsides…”

Challenging – or embarrassing – as that is, the other big hurdle was making an impactful story about the “preciousness of family life with a few fart gags in it” without any dialogue, save for the odd 1,589 ‘baas’, that is.

Did they ever want to cheat a little and add some spoken language?

“All the time,” says Golly with a smile. “All the time, I’d think, ‘I just want it to say. . .”‘

“What’s interesting to us is, there’s a maxim that when you watch a well-known film, you could watch it without the sound on and still get the story,” adds Burton.

“We tried to create a really emotional big story, with a beginning, middle and end. There have only been a few places where we’ve thought, ‘Ooh, it would be lovely to cheat here’. It’s been a tough challenge at times, but it’s been really interesting.”

Hard work as it was, both Golly and Burton are hopeful that fans will want to see more of Shaun on the silver screen.

“We have to think about a sequel, just in case,” says Golly. “Hopefully there will be one.”

BEHIND THE SCENES

- Nick Park, the creator of Wallace & Gromit and Shaun The Sheep pops up in the film as a bird-watcher who gets pecked by a pair of love birds.

- 21 Shaun models were used in total, each taking a week-and-a-half to make from scratch.

- Each Shaun stands at 17cm tall and weighs 100g.

- Over 80m of fleece fabric was used to cover the flock. The fleece has to be stiffened with a spray of diluted PVA glue, to prevent it ‘boiling’ under the studio lights and moving around when the animator touches it.

- The tiniest props used in the film were Bitzer’s whistle, the Farmer’s glasses and Shaun’s tape recorder.