The Oscar-winning director Davis Guggenheim’s arrival in the UK to discuss his latest film comes with little of the usual fanfare.

Instead of the red carpets and snap of cameras most films receive, the director has been sent to a hush-hush location where he awaits a string of journalists who have been sent in a volley of taxis and given a terse briefing on protocol.

But given we’re here to discuss his new documentary, He Named Me Malala, about inspirational Pakistani teenager Malala Yousafzai, the high security levels are to be expected.

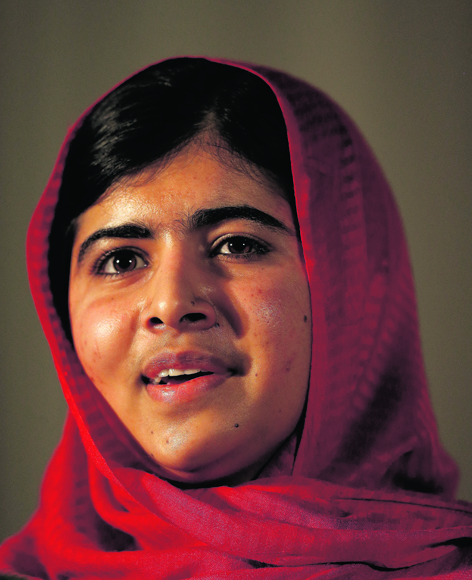

The teenager first came to prominence when she began writing an anonymous blog for the BBC back in 2009, drawing attention to life in the Swat Valley where schooling for girls was being severely curtailed.

The blog was halted, but the schoolgirl continued to speak out about the issue in international press, and eventually won Pakistan’s first National Youth Peace Prize for her campaigning.

But shortly afterwards, Taliban leaders agreed to assassinate the teenager and the then 15-year-old was targeted on her bus home from school, with two of her friends caught in the crossfire (though thankfully, all three have recovered).

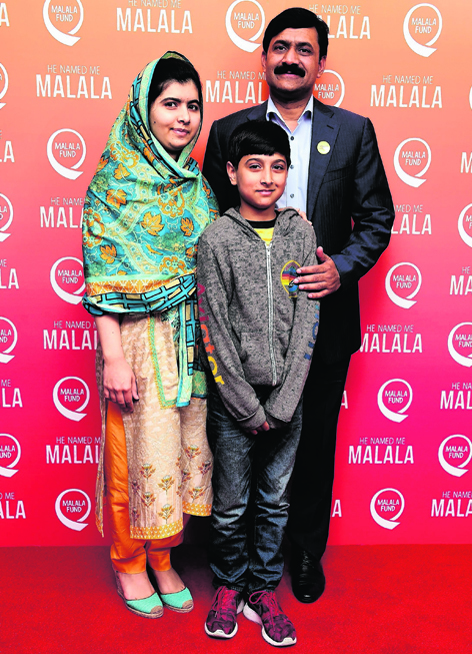

Flown to Birmingham for specialist medical treatment to fix the damage caused by the bullet, Yousafzai and her family have had to rebuild new lives for themselves.

Guggenheim captures this adjustment to the UK and global recognition, as well as the trials of teenage life and the realisation that they cannot, at this moment, go back to Pakistan.

“It’s one of the great privileges in my life to know them and tell their story,” says the film-maker, known for his documentaries An Inconvenient Truth and Waiting For Superman.

“I think I’ll always feel lucky to meet and know them, and tell their story.”

Before the film is released, Guggenheim discusses making the documentary, working with the family and his hopes for the film.

PICTURE PERFECT

To do justice to Yousafzai’s accounts, Guggenheim turned to non-traditional methods of storytelling.

“When Malala spoke about her life in Pakistan, it was almost like a storybook from the point of view of a young girl,” he says.

“Yet when you look at the footage of Pakistan, it’s quite the opposite. It’s those images we’re too familiar with; a scary place with all this conflict.

“So I made this choice to animate those parts of the movie, and animate it from the point of view of a young girl, so you would get the feeling of what she would have felt.”

HOME

Last year, aged 17, Yousafzai became the youngest Nobel Peace Prize winner. Considering this and her numerous other achievements, it’s hard to forget that she also just passed her A-Levels (and not just passed, aced them with six A*s and four As).

Taking this into account, the director was keen to show her domestic life and the relationships she has with her two younger brothers.

“The family would be laughing and playfully criticising each other, and playfully fighting,” he says.

“There was so much joy in the house that I thought it’s important to show this. It’s very easy to tell the story of someone who has done incredible things and think how noble they are . . . but it was important to me to show that they are human beings.”

STORY TO TELL

One of Guggenheim’s great joys was in the very different way the “beautiful family” approached being in front of the cameras.

“Everyone is telling their story these days,” he says. “Everyone is aware of how they look and how they’re perceived and they’re very cynical about how their story is being told on social media sites.

“Malala and her family are the opposite. They’re very open and, for them in Pakistan, the act of telling their story was a critical part of their mission.

“People were blowing up schools, people were terrorised, and telling their story was an act of necessity. Making this movie was an extension of that. It wasn’t just a frivolous act of narcissism to tell their story, it’s a critical part of their work.”

CONCERNING YOU

When it came to it, the director and the family had similar worries about making the documentary.

“I think they were rightfully concerned about how their story is perceived in the East and the Global South, and I shared that with them,” he says.

“I’m a guy from LA. I might tell a story that I like, but will it be misinterpreted? There’s also the translation between one culture to another, so I think that was important to them.

“But they understood that I’m very respectful of that and I never pushed my way into things.”

CALL TO ARMS

Ultimately, the family and Guggenheim hope that the film will inspire people to take action.

“I promised her that I’m going to do everything I can, so that it’s not just a feel-good movie that people watch and move on from,” he says.

“I want it to engage a new generation of people to fight for something that we know works; educating girls works. In this complex world where most problems feel unsolvable and complex, this is one thing that is doable.

“Educating a girl not only changes her life, it changes her family, it changes her village, it changes her nation.

“When you don’t educate girls, cultures and economies suffer, so wouldn’t it be great if this isn’t just a movie, but that it’s also a movement?”

To find out more about the Malala Fund which campaigns for safe, quality education for girls, visit www.malala.org