To so many in the north-east, Robbie Shepherd was beloved.

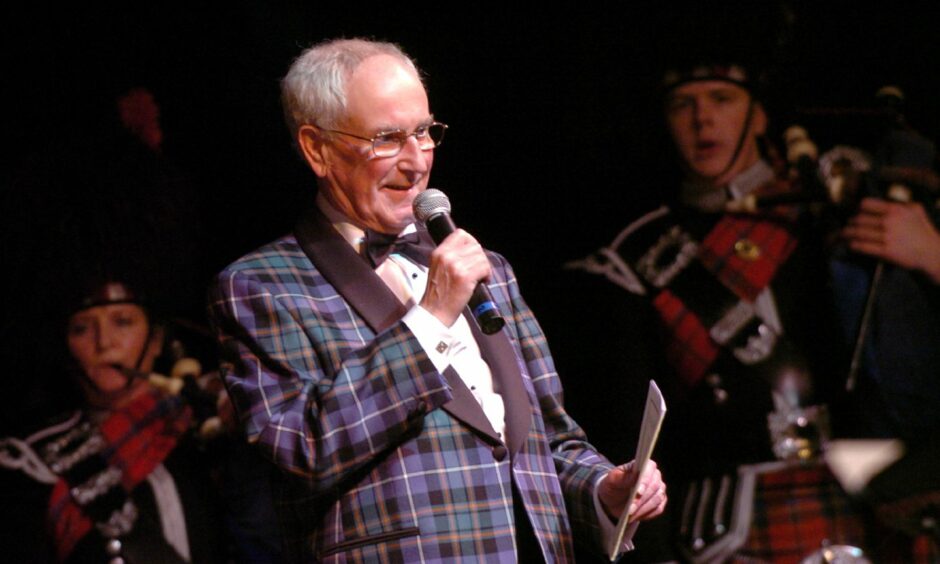

The musician, writer and broadcaster’s lilting Doric tones and well-kent face were a household staple for over four decades.

His years spent championing the tunes close to his heart on BBC Radio Scotland, becoming the long-standing voice at the Highland Games and even receiving a royal nod in 2001 for his services to Scottish music and culture made him a “national treasure”.

When Robbie died aged 87 on August 1 last year, he left behind many a broken heart not least of those being that of his wife, son, siblings and two grandchildren.

Sharing him with many across the country in death as they did in life, his son Gordon said: “It was certainly comforting to know there’s that much love for him.

“I bumped into a couple of ladies from Aberdeenshire down in London… they said he was much-loved which was touching.”

‘I used to not like the way my dad spoke’

While Gordon said he is proud of his father’s legacy, it was not always that way.

As a child, he thought his dad’s way of speaking was strange.

He said: “I didn’t like the way that he spoke when I was young.

“And he said ‘The way I spik puts clothes on your backside’.”

It is just one of the stories being shared by Robbie’s family, who gathered in the hallowed halls of the Atholl Hotel in Aberdeen – a favoured spot of the Dunecht loon – on the anniversary of his death.

Gordon, who travelled up from south of the border with his wife Lucy and two children Dougie and Rose, was joined by his dad’s sister Helen Philip, brother Harry Shepherd and his wife Evelyn, and entertainer, presenter and Robbie’s friend, Robert Lovie.

And in the quiet of an upstairs room over cups of tea and coffee, the family recounted all their memories of the entertainer.

A childhood filled with polishing boots, cricket and Sunday ‘fishing’

Before Robbie became the man Billy Connolly chased for a photo at the Lonach Gathering, he was born the middle child of his parents Harry and Helen Shepherd.

He and his siblings were brought up in Shoemakers Cottage in Dunecht where their father’s trade became part of their routine.

Especially with their house being attached to the shop.

They were all expected to pitch in with the chores which included helping polish the shoes in the shop by cracking the big finishing machine.

Even when the boys got bursaries to attend Robert Gordon’s College, when they came home, the polishing came first before their homework or tea.

When asked how long this would take, Harry, 90, said: “It depended on how busy that day had been. Our dad made all the boots for the estate as well so there was a lot of preparation.

He joked: “This is why I have one leg stronger than the other.”

Cricket brought out Robbie’s competitive side

As siblings, they all got on well with Harry saying they would get “a skelp on the backside if we didn’t”.

Sharing a love of football and cricket, it was the latter which brought out Robbie’s competitive side with his brother.

When playing on the nearby back green, they would often pose as their favoured players: Robbie as Dennis Compton and Harry as Bill Edrich.

On Sundays, the boys would be pulled out of bed at 3am for “fishing” with their dad at the laird’s own loch.

This fishing would always be left just before the gamekeeper woke up at 5am and Helen would often be greeted by the welcome sight of fresh trout for breakfast.

Every Friday at the Atholl Hotel for mince and tatties

Their mum who was a music teacher, played the piano, and as Helen said “tried to learn us” but with little effect.

Nevertheless, as a family, their delight in Scottish dance music grew from listening to the wireless on a Saturday and being two doors down from the village hall where the tunes from visiting bands would easily travel to their side of the wall.

As they grew up and went into different lines of work, Harry, who did radioactive service at Macaulay Land Use Research Institute (or what is now the James Hutton Institute), would meet Robbie, who pursued accountancy, every Friday.

It was on the bus into the city that Robbie met his wife Esma Dixon who shared a love of music.

With Robbie on the accordion and Esma on the piano, in their spare time, they played with the Garlogie Four and Robbie started compering at Highland games.

When Robbie later started working for the BBC, the brothers always gravitated towards the Atholl Hotel just up the road from the studio for their weekly meet.

“I wonder why,” joked Helen.

Harry quickly replied: “The mince and tatties of course.”

Claiming the hotel served the best in Aberdeen, Harry said Robbie was always chatting to people.

“Especially after the third or fourth dram,” he added.

‘He was just family’

Helen, however, would visit Robbie and Esma at Balgownie Crescent and often pitched in with the gardening – a hobby their parents passed down to all their children.

For the brother and sister who witnessed Robbie’s first days commentating on the cars and motorbike races at Garlogie and Dunecht, to attending garden parties with the Queen, they said they were always very proud.

But through it all, the “nae fuss” loon never failed being their “caring and ill tricket” brother.

“He was just family,” said Harry.

When asked how he stayed so grounded and humble, Helen modestly added: “It was just the way that he was.

“We were just a normal family.”

Robbie knew someone everywhere they went

When Robbie’s son Gordon was around 10 years old, his dad was at the height of his career.

Prepping and recording five radio shows a week, Robbie was frequently pulled away from home.

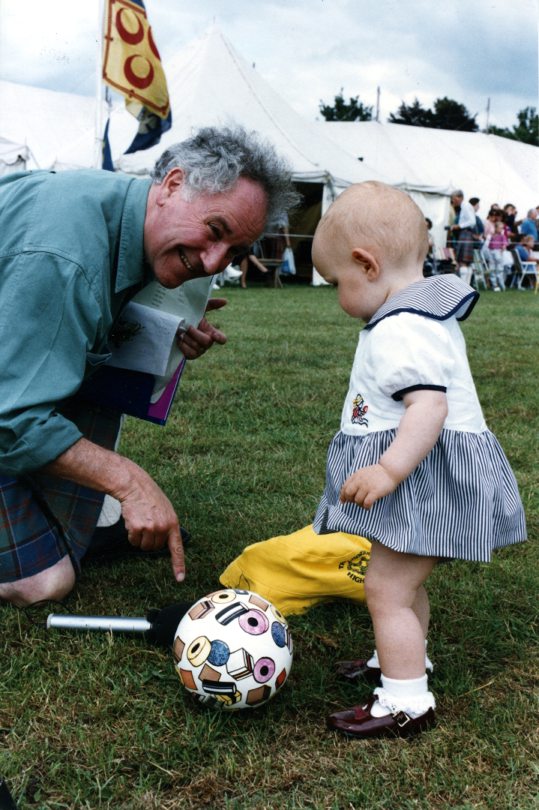

Often dragged around all of the Highland Games, as Robbie’s son, Gordon would play on all the tractors and machinery and be able to stroll on to the park’s centre stage.

At the time, he just thought the perks were normal.

That, and the fact his dad would stop and chat to someone everywhere they went.

“Even when we were abroad on holiday that would happen,” he said.

“He’d know somebody or somebody would know him. Nae that we went abroad very much… They didn’t like the heat, mum and dad.

“I suppose you don’t realise why does everybody know my dad when you’re young. You just think it’s normal, but it’s obviously not.”

His dad’s way with people extended to their home with musicians like Aly Bain often visiting.

Gordon said: “It was a bit of a running joke. You didn’t have to ring the bell and wait, you could just ring the bell and walk in… It’s like an open house.

“There were always musicians in the house, it was always a bit of a party house, especially around Christmas and New Year. There would be ceilidhs.

“I would be upstairs supposed to be in bed but you obviously can’t sleep.”

Pittodrie toilets became half-time hideout for Gordon

When Robbie was at home, father and son bonded over their love of sport.

With cricket being the “one thing they supported England at”, they also held season tickets at Pittodrie for years.

The only thing that soured the memory was when Robbie’s song Up the Dons would play.

“That used to embarrass me,” Gordon revealed.

“I used to go to Pittodrie a lot and my pals used to say ‘I’m going to request that song at half-time.

“I used to hide in the toilets. But now I’d love it if it came on. He also hated it.”

Early on Sunday mornings, Robbie would drag his teenage son to the Dunecht golf course, which had mixed reactions.

“I think he tried to tame my temper,” Gordon said. “I nearly hit him with a golf club once after launching it in the air.”

There was one hobby which did not get passed down: “At home when he did have downtime, he [and mum] would be out in the garden. He’d try and get me involved with that when I was younger.

“I think the most he got out of me was cutting the grass.”

‘I just felt incredibly lucky and just extremely proud to call him my dad’

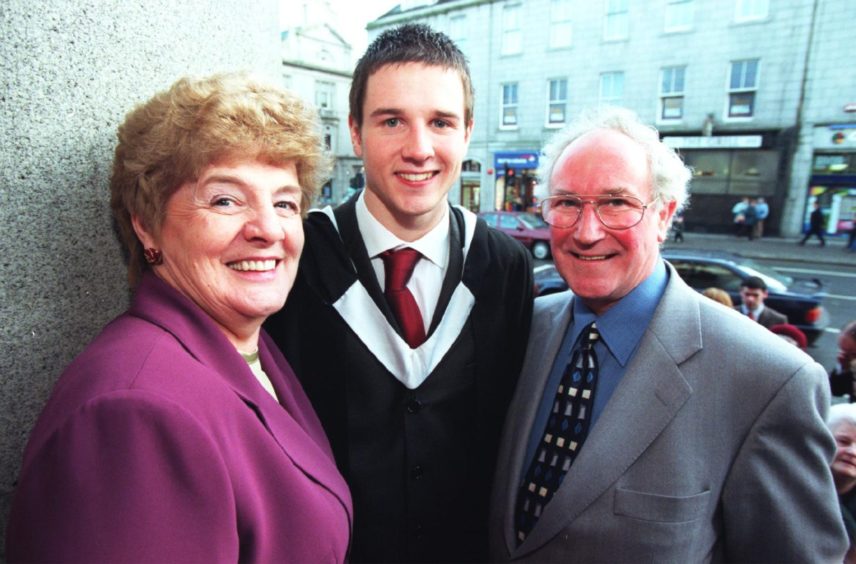

As Gordon grew up, they shared a head for numbers.

Gordon remembers his dad being proud of him going to Robert Gordon’s University to study maths and computing, while Robbie had studied accountancy in his youth at Robert Gordon’s College.

Once he started bringing his own kids to visit their grandparents, Gordon and the family shared happy memories of the grandchildren dancing in the living room with Esma and Robbie to Scottish dance music.

A visit to the Atholl Hotel was always in order and Gordon and Robbie would go to the local pub in Bridge of Don where Robbie had his own stool and glass.

When Gordon and Lucy were able to take Dougie and Rose to Braemar, Gordon said: “I was proud to do that and show them their grandad.”

Finding it hard to think it had already been a year since his dad passed, Gordon added: “I just felt incredibly lucky and just extremely proud to call him my dad.”

Robbie Shepherd’s legacy projects

In order to commemorate the brother, father, grandfather and friend, Robert Lovie and Robbie’s family have organised a series of initiatives to preserve the memory of the broadcaster.

These include offering bursaries like the ones Robbie and Harry benefitted from as boys, a sweet pea garden, erecting a granite memorial cairn on Dunecht Estate and hosting a concert on October 20 at His Majesty’s Theatre.

And in other ways, the family still hear Robbie’s voice today.

Even now, Harry said they still love to listen to their brother’s voice on the radio.

“He’s still on the radio these days. On a Sunday night with Gary Innes about once a month he’ll say ‘Here’s Robbie playing the accordion or an old recording.’

“We listen to Gary every week.”

A Toast Tae Robbie Shepherd on October 20 2024 at His Majesty’s Theatre will feature a wide range of well-known Scottish musicians, dancers and performers.

From Scottish dance bands to fiddlers, those taking part include Karen Matheson, Donald Shaw, Aly Bain and Violet Tulloch. For more information and tickets, you can visit aberdeenperformingarts.com

A Go Fund Me page has been set up to help fund the Robbie Shepherd legacies. For those interested in donating, you can find the page here.

Read more My Family stories here

- ‘Death is our life, and always has been’: Meet Kathleen MacIntosh and her family of Bridge of Don funeral directors

- ‘Pascal’s parents wouldn’t even look at him’: Aberdeen mum on Down’s syndrome adoption journey

- Jiu Jitsu father and son from Laurencekirk on dealing with bullies and respecting their deadly craft

Conversation