In Donald S. Murray’s visit to the port of Scheveningen on the Dutch coast, he came across a photograph in the town’s museum

It was of a place that was familiar to me – the graveyard at the top of the Knab, the sentinel of rock that stands guard over Lerwick. Two men stood at its lower edge on a grey Shetland day, one wearing the hat, coat, collar and tie most adult males seemed to have been kitted out in the mid to late 1970s. The other was clearly speaking to a small, invisible gathering, a poppy on the lapel of his dark suit, the crisp-white cuffs of his sleeves showing as he brandished his arms while addressing both them and the stiffness of the breeze. They stood beside a newly erected, white headstone which had been set within a dark wooden frame. At its top, written in Dutch, was a reference to Psalm 65, verses 5 and 6.

Therefore the ends of all the earth,

and those afar that be

Upon the sea, their confidence,

O Lord, will place in thee.

Who, being girt with pow’r, sets fast

by his great strength the hills.

Who noise of seas, noise of their waves,

and people’s tumult, stills

Among the words carved – both in Dutch and English – on the stone was the following inscription: ‘In Memory of the Dutch Seamen who died at sea or in this country and who were buried in this graveyard in the years 1875–1926.’ There were the names, too, of the fishing ports that had come together to put up this small monument. They included communities like Vlaardingen, Maassluis, Katwijk aan Zee and Scheveningen – each cluster of vowels and consonants alien and strange when read in the cold November light of Shetland, as my wife and I had done. Alongside them were a number of other stones, often with the words ‘Hier Rust’ inscribed on the crest; the names dated from the early years of the twentieth century, winnowed and sometimes made illegible by the scour of wind and salt. Two of them are from Scheveningen: fifty-three-year-old Cornelis de Best, whose date of death is given as 19 July 1906, and Willem Dijkhuizen, who was only twenty when he perished on 5 June 2005.

And then there are the others who lie in the Lerwick graveyard, the ones who are unnamed and possess no individual stones or markers to establish where exactly they might lie – a mingling of names and ages, ranging from sixteen to fifty-seven, each one dying for whatever reason, illness, mischance or accident, their corpses lying alongside a young woman from my own native island, who died while gutting herring away from home. In an article written to accompany the unveiling of the Lerwick memorial, we note their identities and ages – Martin Harteveld, aged seventeen, Klaar Pronk, sixteen, Hendrik Jacobus Johannes Oosterbaan at nineteen, paying particular attention to the younger ones, as if there is some greater, more overwhelming tragedy connected with their youth, more difficult to imagine than the others. Forty-six-year-old Machiel Vrolijk, whose absence from his home might have hurled a wife into a world of grief and darkness, set children on a path where the only possible destination was despair. Job Michiel Taal, who might have wondered, like his Biblical namesake, why death and loss had come for him in his fifty-sixth year…

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Donald S. Murray comes from Ness in the Isle of Lewis but now lives in Shetland. He has written widely about island life – from his beginnings as a weaver’s son in Weaving Songs to the Italian Chapel in Orkney in And On This Rock.

He has also written extensively about one particular bird – the gannet (or guga). His book, ‘The Guga Stone; Lies, Legends and Lunacies From St Kilda’ was chosen as one of the Guardian’s ‘Nature Books of The Year’ in 2013. His book ‘The Guga Hunters’ was highly praised by the critic, Will Self in ‘The Daily Telegraph’.

His play Sequamur – produced by Proiseact Nan Ealan, the Gaelic Arts Agency – is being performed at In Flanders Field Museum in Ypres on September 4, 2015.

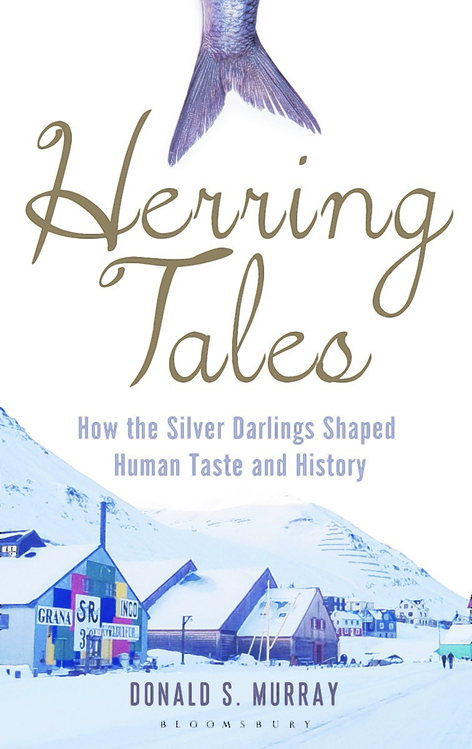

Herring Tales – published by Bloomsbury Publishing on September 10, 2015, hardback, £16.99 – features a journey around the old herring ports of Europe, from Florø in Norway to Siglufjörour on the north-eastern edge of Iceland, with a few places in the north of Scotland en route. It examines both the history and legacy of the industry, looking at how the most important fish ever to swim around Scotland featured in the life, work, politics and even humour of northern Europe. It will be launched at the Skye Book Festival on September 3, 2015.