He’s a shining light on the screen and stage, but Alan Cumming’s early years were often dark and painful. The Scots actor tells YL how, while he’s forgiven the abusive father, he’ll never forget

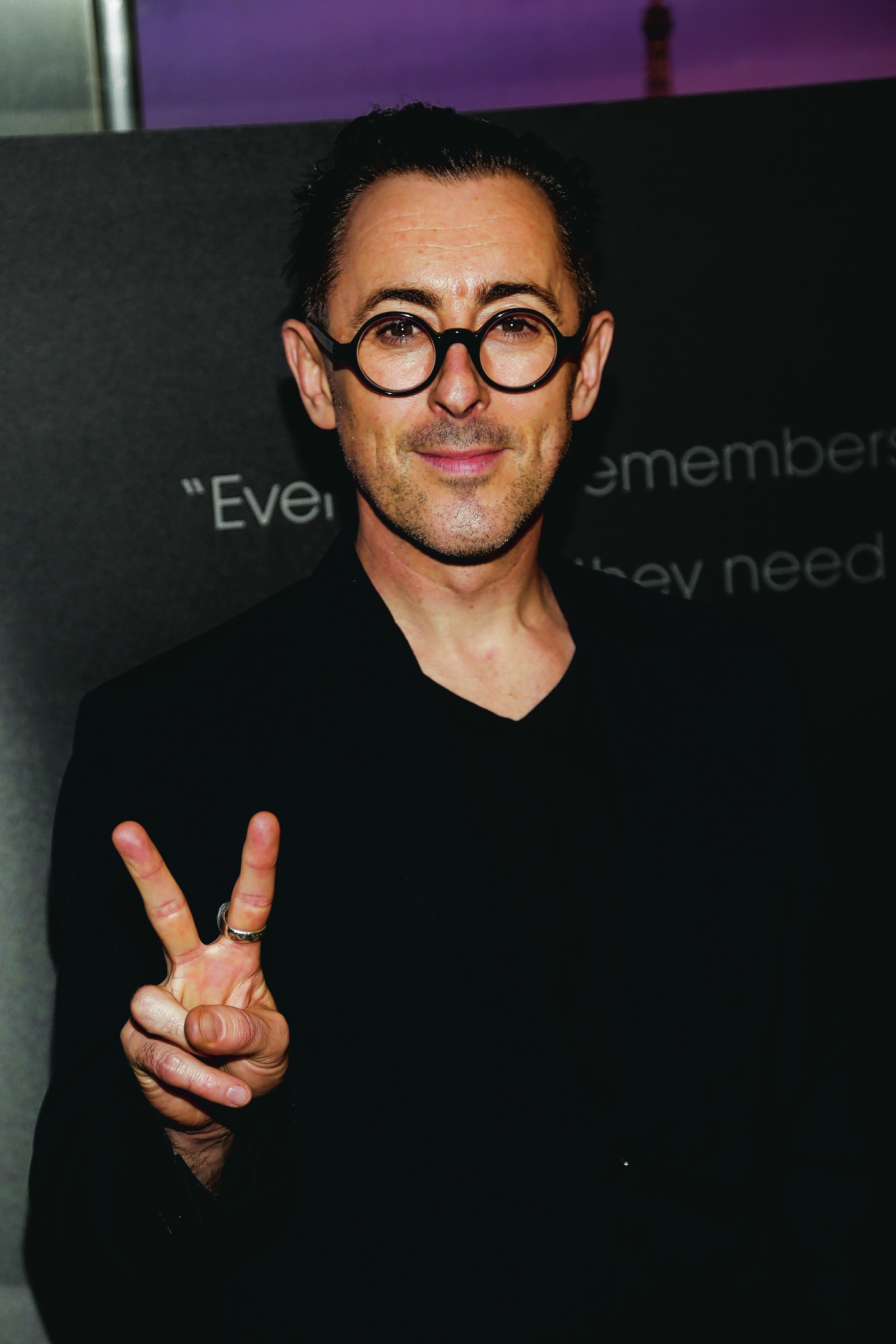

Alan Cumming seems a little tense initially when we meet to discuss his memoir, Not My Father’s Son.

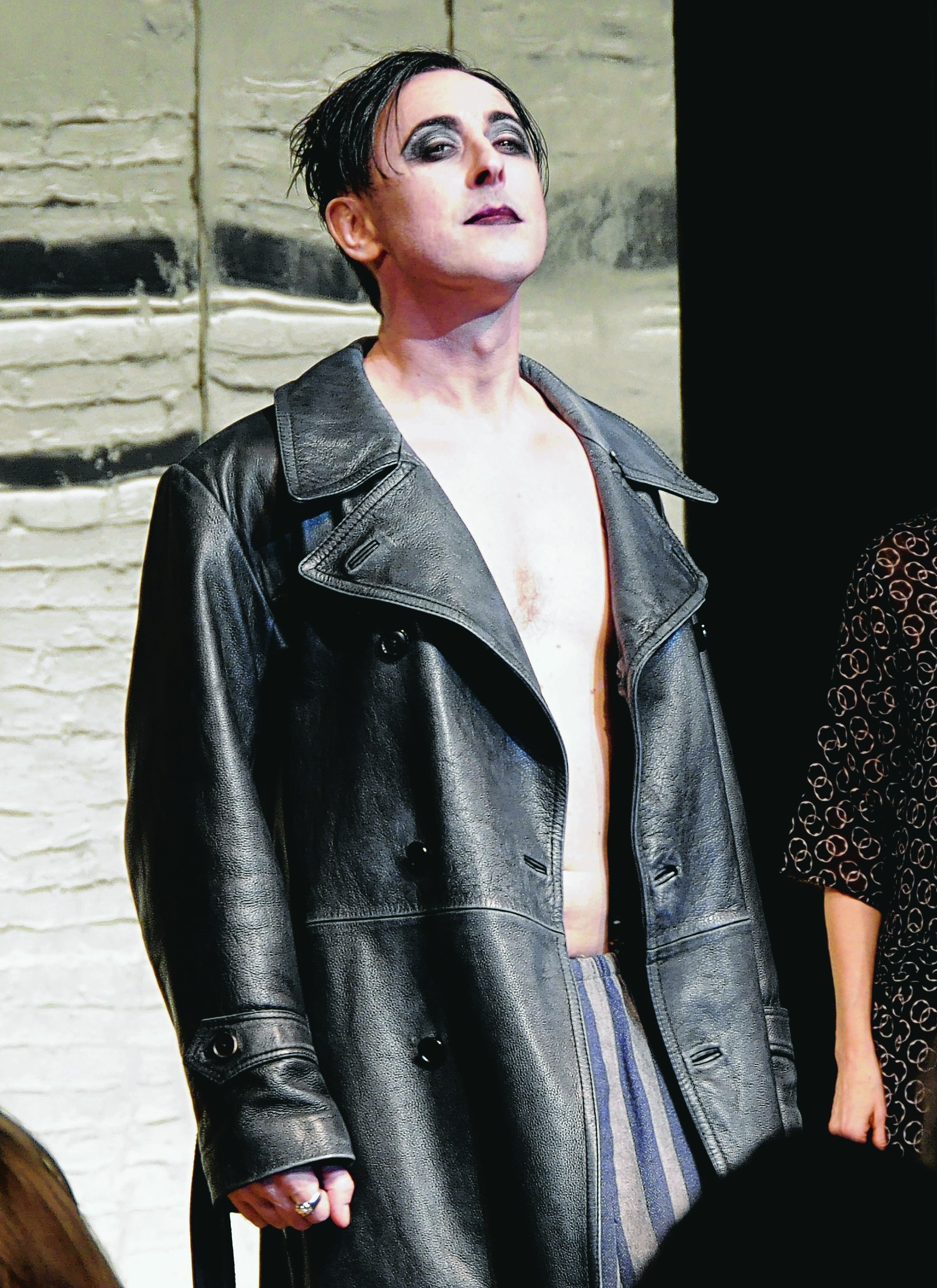

The gregarious actor – who is currently playing Emcee in Cabaret on Broadway to standing ovations and is filming a new series of the Emmy-winning The Good Wife, in which he plays sharp-suited spin doctor Eli Gold – is on a whistle-stop visit to the UK before returning to his home in New York, which he shares with his husband Grant Shaffer.

Raking his dark hair with his fingers, Cumming’s slight edginess is understandable considering the prospect of discussing the very personal content of the book, in which he reveals the cruelty that he, his brother Tom and mother Mary, received at the hands of his father.

RITUALS OF HUMILIATION

Alex Cumming, a brute of a man, head forester on the Panmure Estate near Carnoustie, systematically taunted and terrorised his wife and two boys through rituals of humiliation, physical and psychological abuse, and openly had extramarital affairs, refusing to ever process what he’d done.

His idea of giving the young Alan a haircut was to shave his head with a pair of rusty sheep shears, holding him down like an animal and cutting his skin. He would set him tasks with little or no instruction then beat him when he didn’t do them properly.

“His actual violence towards us rarely lasted beyond one or two really hard whacks, the odd kick,” Cumming, 49, writes. “I actually think the prolonged period of tension before landing his blows, as we were systematically inspected, chided and humiliated, had a far worse effect than the actual hits.”

Mary left her abusive husband – who promptly installed his lover in her place – when Cumming was 19 and at drama school in Glasgow. The couple later divorced.

The savagery, Cumming’s escape into acting and his efforts to understand his father’s actions are all documented, along with the efforts that he and his brother Tom made, unsuccessfully, to try and re-establish some sort of relationship with him later on.

After no contact for 16 years, another bombshell was dropped in 2010 when Alan agreed to appear on the BBC genealogy show Who Do You Think You Are?

His father, by then dying of cancer, rang his brother, telling him that Mary had an affair and Cumming was not his son. He said he didn’t want it to come out in the programme.

DNA TESTS

Cumming and Tom decided to take DNA tests, to see if their father’s claims were true – we won’t spoil the book by revealing the result.

The terrorisation had many repercussions in Cumming’s adult life. In the early Nineties, he had a nervous breakdown, which he calls “Nervy B”, stemming from all those years of tense silence, all those years of bottling things up.

At that point, he had been married for seven years to actress Hilary Lyon when they decided to try for a baby. However, the notion of becoming a father sparked memories of his own traumatic experiences growing up.

“The issues around having a child brought up the memories of what had happened. It manifested itself in severe depression, anxiety and powerlessness. I stopped eating. Then I slowly realised that what it was about was to do with my dad, and that was really terrifying,” he recalls.

He started having panic attacks, became agitated and irritable, stopped engaging with friends and alienated himself from his wife. They ended up divorcing, he holed himself away to try to sort himself out and ended up having a lot of therapy.

Work, friends and family have helped him through it. Today, his life is busier than ever, what with TV and theatre work, as well as his “Club Cumming” after-parties in his dressing room, when celebrities, cast members, friends and hangers-on keep the revelry going until the early hours, as documented on his Instagram feed.He even has an alcohol sponsor, Campari America, to keep the drinks flowing.

“Sometimes, because of the parts I’ve played, people think I want to jump on the bar and make a speech, but I don’t. I love Club Cumming in my dressing room at Studio 54, when it’s with people I know. I like letting go.”

His childhood may have been without joy, but he is now making up for lost time.

He’s lived in New York for 16 years and is in the process of renovating a town house in the East Village in Manhattan. He also has a pad in Edinburgh, but doesn’t return much because of work commitments, he says.

ODDBALLS

“New York’s a city of people who are different. It embraces oddballs. We would never want to live in Los Angeles, which is just a work town. New York is a really exciting city because people are interested in the world. LA’s just interested in the entertainment industry and money.

“I was there a wee while ago and a waiter came up to me and said, ‘Congratulations Alan’, and I said, ‘Oh why, did I win an award?’ And he said, ‘Oh no, your movie took 25,000 dollars at the box office this weekend’, and I thought, ‘How do you know that?’ I was horrified that the waiter knew that.”

In parallel with the story of his father, in the book he charts the fascinating account of what became of his maternal grandfather, Thomas Darling, a decorated soldier who died in a “shooting accident” in Malaya shortly after the war, at the tender age of 35. It turned out he was playing Russian roulette. Another shock for Cumming.

Perhaps there were mental health issues among men on both sides of the family? It’s something he has considered.

“Tommy was a great, respected and decorated soldier, but also a daredevil, a cheeky chap, and in search of something.

“He was charismatic and quite reckless, and I’m quite reckless. I wonder if the reason my granny and I were so close is because she saw a bit of him in me.”

“I’ve had a bout of it, mental illness, when I had the nervous breakdown,” he continues. “I went under for a while but I don’t worry about it now. The situation with my dad gave us some ammunition about how to deal with people’s violence and rage. In my life, and especially in some of the work I do, there’s a propensity to slip into a dark place and I’m very conscious of that.”

He now believes that his father, who died in 2010, was mentally ill saying: “In a way, it’s easier to think he was just this nasty, evil person, but I think there’s evidence to suggest there was more to it than that.”

That thought helps him cope with the memory of how cruel he was.

VINDICTIVE TYRANT

He added: “It’s not a salve but it makes it easier to release it. He was psychotic, a nasty, vindictive tyrant.”

He says in the book that he’s forgiven his father. It’s clear, though, that he will never forget.

“In writing the book, I’ve brought him back into my life, and he will be there forever,” says Cumming. “I’m not putting it to bed. In a way, that’s my intention.”

Not My Father’s Son by Alan Cumming is published by Canongate, priced £16.99.