To military officials it was known as Special Training School Number 103.

To those who trained there it was simply ‘the secret military camp’. But to history it became famous as Camp X, the top secret World War II spy school in sleepy rural Canada, where Allied secret agents learned their deadly craft.

And now Camp X has inspired a critically acclaimed, hit TV drama series, X Company, about the daring exploits behind enemy lines of those trained at the facility.

“It tells the story of five highly skilled new recruits from Canada, the US and Britain who have been torn from their everyday lives to train together as agents at Camp X,” explains a programme spokesperson.

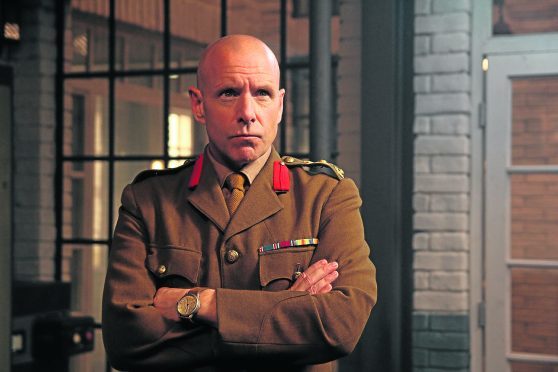

Starring British actors Jack Laskey and Warren Brown, recently seen in ITV’s Liar, X Company “combines spy craft, glamour, grit and gadgets with fast-paced action, intrigue and passion,” promises the series’ producers.

Perhaps even more thrilling and unbelievable than any of the plots concocted by the scriptwriters of X Company, however, were the real-life wartime heroics of Camp X’s chief instructor, a tough Scotsman known as ‘The Wild Highlander’.

Built on the shores of Lake Ontario, near Oshawa, in 1941, Camp X was set up to train agents of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), Churchill’s elite secret army put together in the summer of 1940 to “set Europe ablaze”, in his words, by carrying out guerrilla-style attacks on German forces in Nazi-occupied territory, especially France.

Camp X’s first commanding officer was Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Roper-Caldbeck, who joined the SOE from the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders in 1941. He led a colourful collection of hard-bitten instructors, many of them Scots, who whipped the raw recruits into shape.

Among them was Captain Hamish Pelham-Burn. Born in Nairn in 1918, Pelham-Burn was raised at Kilmory Castle in Argyll, and it was during his childhood in rural Scotland that he learnt the skills that would later make him such a formidable commando and effective instructor, spending his formative years hunting, fishing and climbing.

But the young Hamish was also proving to be a restless spirit, with a taste for sabotage that would later serve him so well in wartime.

Loathing the primary school in Sussex he’d been packed off to and yearning for his Scottish homeland, he attempted to set it on fire.

After attending Sandhurst, he was commissioned into the Seaforth Highlanders, his father’s old regiment, and in World War II saw some early action during the brief battle for France in May 1940. Caught up in the chaotic Allied retreat to the Channel ports following the collapse of the French army, he made it to Cherbourg on a purloined motorcycle.

Back in England, his military career then took a surprise turn when he volunteered for the RAF, learning to fly Hurricane fighters and carrying out low-level hit-and-run attacks on enemy targets in northern France.

But a severe sinus infection brought his airborne career to a halt and, craving action, he joined the SOE and underwent intensive training at the commando school at Arisaig in the summer of 1942.

Fiercely proud of his Highland roots, he was usually to be seen in his kilt and shocked some of the English recruits when, after going out on a hunting expedition around Arisaig, returned to the camp one day dragging the body of a 300lb stag he shot. It was antics such as these that earned him the nickname ‘The Wild Highlander’.

His leadership qualities were soon recognised by his superiors and it was felt that he would make a fine instructor himself. After receiving parachute training with the RAF, he was sent on his first mission into occupied Europe, dropped into the Vercors region of eastern France to train French resistance fighters.

Arriving safely back in the UK, in early 1943 he was sent across the Atlantic to join the team of elite instructors at the top secret Camp X. Among those said to have spent time at the camp during this period were the future best-selling novelists Roald Dahl and Ian Fleming, a naval intelligence officer during the war and who, some claim, gained inspiration for James Bond from some of the spies and saboteurs who were trained there.

At Camp X, Pelham-Burn trained the new recruits hard. He used Tiger Moth biplanes borrowed from the Royal Canadian Air Force to train agents in night-time pick-ups from small fields. But his speciality was demolitions, and in particular teaching the agents the most effective means of sabotaging the enemy’s rail network.

“Agents learned that derailment caused the enemy some headaches, but could be repaired in a few hours and really proved to be little more than a nuisance,” explained Camp X historian Lynn Philip Hodgson.

“A truly effective delay could be caused by taking out a site such as a bridge or a viaduct, which could potentially take days to reconstruct, and required a greater number of personnel to complete.”

The basic course lasted 10 weeks and was immensely demanding, both physically and mentally. With live ammo used on all exercises, it could also be almost as dangerous as the actual missions the recruits would eventually be sent on. But those who passed the course became some of the most formidable warriors of World War II.

“All in all,” revealed Hodgson, “it was very rigorous, extensive training and they emerged from Camp X hardened beyond any other military, physical, mental or emotional experience that they would endure in life.”

Like most of the Camp X instructors, Pelham-Burn also took part in missions behind Nazi lines, and he personally led one of the most important commando operations of the war.

On June 3, 1944, just three days before D-Day, Pelham-Burn and two fellow Camp X trainers, Sergeants Andy McClure and Jack Clayton, parachuted from an RAF Wellington bomber into Brittany. Their mission: to knock out a vital German radar installation, which could detect the Allied invasion fleet as it approached Normandy on June 6.

After taking care of a German guard at the site, the saboteurs attached explosive charges to the radar antennae mast, set to go off 20 minutes later. But just as the team was making its withdrawal, one of the charges went off prematurely.

While the explosives had completely destroyed the target, the thunderous explosion brought a group of enemy troops stationed in a nearby hut rushing to the scene. Fortunately, the three instructors were as handy with a Sten gun as they were with plastic explosives, and soon all the Germans lay dead.

Hunted across the Breton countryside by angry enemy soldiers, Pelham-Burn and his team were hidden by the French Resistance for the next five days before being retrieved by a small RAF Lysander aircraft and brought back to England.

Other SOE agents trained at Camp X were also active in the days leading up to the Normandy landings, helping to bring the rail network in northern France to a virtual standstill and delaying the arrival of German reinforcements by vital days, which allowed the Allied armies to secure their hold on the beaches.

“Of 1,050 rail demolitions asked for by Allied Command, 950 have taken place,” Brigadier Colin Gubbins, the Scots chief of SOE, proudly reported to Churchill after D-Day. “The rail network is paralysed and German traffic, driven on to the roads, has run into countless roadblocks.”

Following the success of D-Day, Pelham-Burn’s raiding career came to an end. He finished the war serving as a liaison officer at SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force) in Versailles.

After the war, he returned to his beloved Scotland, spending the rest of his days in Perthshire, where he indulged his passions for mountaineering and golf.

He died at the age of 92 in February 2011, a relatively little-known figure in his homeland but a man revered in Canada for the part he played in turning Camp X into the Allies’ premier school for spies.

“Hamish is a very loved and famous man over here in Canada,” revealed Hodgson, who befriended Pelham-Burn in his later years.

Camp X, meanwhile, became a secret Cold War listening station, run by the Canadian military, until it was finally closed down in 1969.

Today, very little remains of the original camp, although a memorial now marks the site where Hamish Pelham-Burn, ‘The Wild Highlander’, and his fellow instructors trained so many brave young men and women, and whose heroism, as the TV series X Company reveals, helped turn the tide of World War II.

X Company is currently on the History Channel every Tuesday, at 9pm.