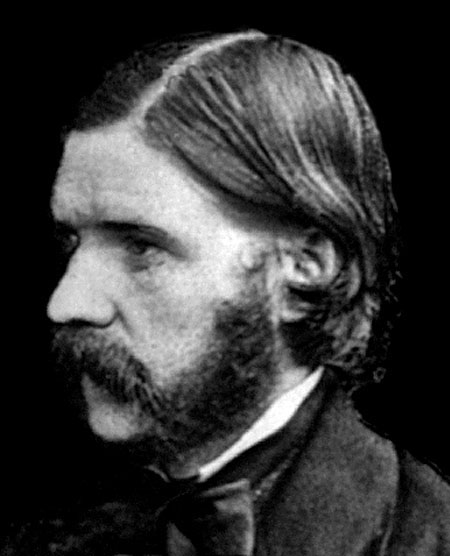

Pioneering photographer George Washington Wilson was a familiar sight on the streets of Victorian Aberdeen, smoking a cigar at the reins of his portable darkroom, pulled along by his horse, Tommy.

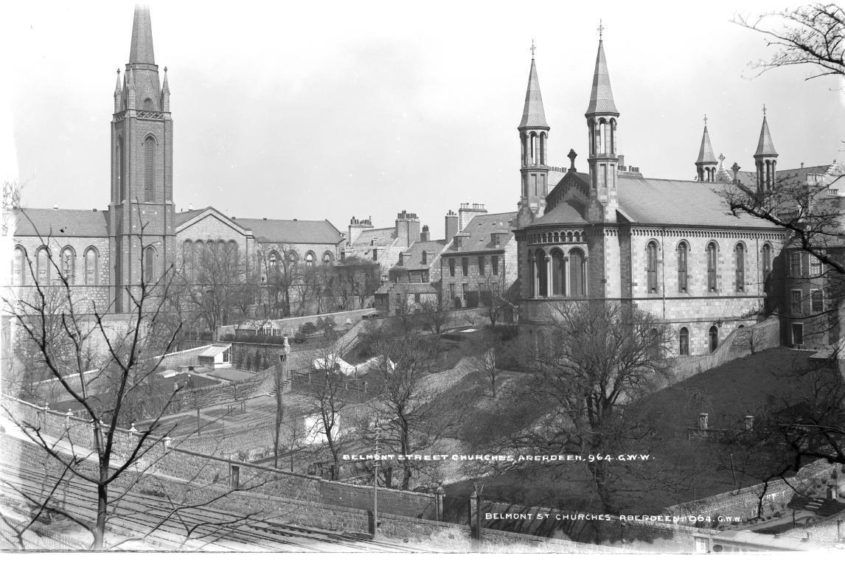

The images he took of the Granite City from the late 1850s to the 1870s offer a fascinating window back in time to the days before cars, when the streets were lit by gas lamps, and a camera was a thing of wonder for ordinary people to behold.

Yet so many of Wilson’s crisp, beautifully composed photographs – so rich in detail you can even read adverts in shop windows – have rarely or never been seen in public.

That’s something Ashleigh Black wants to put right with an exhibition of his street scenes, drawing on the George Washington Wilson Collection of the University of Aberdeen, which contains more than 38,000 glass plate negatives by the photographer and the firm he created.

The PhD student in film and visual culture is writing her thesis on Wilson and hopes bringing more of his work into the public eye, especially images of Aberdeen, will let people appreciate a man she believes has not been given enough credit for bringing modern photography to the world.

“He got quite a few images from the towers of the municipal buildings across Aberdeenshire, so you have these beautiful spanning views of the rooftops and skylines of Aberdeen,” said Ashleigh, 25.

“You didn’t really get that in those days.

“Photography then was portraiture or beautiful countryside.

“You don’t see the industrious Victorian side, the granite buildings and everything.

“His cityscapes were a way of showing Aberdeen to the world.

“It’s him saying: ‘Look, this is my city, it might be grey and granite, but it’s beautiful – this is the city that Archibald Simpson and John Smith built’.”

Wilson is, rightly, famous for his stunning portraits of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert taken at Balmoral, which earned him the prestigious title of Photographer Royal in Scotland 160 years ago, in 1860.

But it his urban images which Ashleigh is concentrating on for both her thesis and her exhibition.

She said Wilson took many pictures of the Castlegate, the Belmont Street churches, King Street and Union Street, mainly from an aerial perspective. But Wilson, who described himself as an artist first and foremost, also got down on the ground, showing everyday street life in Victorian Aberdeen.

“The street level photographs are interesting, because he wasn’t commissioned to take those,” she said.

“So you see people going about their daily lives.

“Some of them turn toward the camera and there’s a question as to whether or not he asked them to be there.

“In quite a lot of his photographs there are children in the background. There is a hanging question as to whether he posed them there or not. Really, his eye wasn’t focused on the people. It was the infrastructure, the city as a wider image.

“With GWW he is on the ground, but he is not there to capture the people, but to capture the atmosphere.”

Ashleigh said in his earlier work the streets look deserted but in reality they were not. The exposure times were so long, up to eight minutes, anyone walking in the shot would have been gone leaving only a ghostly blur walking across the road.

For his earlier work, Wilson toured the streets with a van he made himself, which was a portable darkroom.

“It was pulled by his horse, Tommy, and they were a regular sight in Aberdeen,” said Ashleigh, adding he would often be puffing on one of his much-loved cigars.

Wilson’s later images clearly show carriages and people, a testament to the rapid development of photography, pushed along by the work of Wilson and his contemporaries.

“You can see the bustling life,” said Ashleigh, adding it is a remarkable snapshot of Aberdeen at that time.

“I think he chose his perspectives quite well.

“The ones of the Castlegate really intrigue me, because when you look at it then, it was such a bustling space.

“It was a market place, it had a fence around the Mercat Cross, which isn’t there anymore. That was almost like a sacred space. But it was still a communal space. It’s where people came to talk and gossip, women came out to meet their friends, they set up market stalls.

“But now it’s almost like an empty space. People still walk across it, but there’s not the same kind of community or buzz around it.”

Ashleigh said looking at Wilson’s photographs from the perspective of 2020, made her realise Aberdeen hasn’t really changed that much.

“It is definitely a city that has stood the test of time and that’s quite remarkable.

“It gives the city an enduring identity.

“Looking at them now and seeing the photos of the Castlegate and people going about, you think these pictures have immortalised these people, whether or not they realised it.

“Being able to look at them on a computer screen, to zoom in and see their faces and some of the old advertising slogans in the background is really amazing,” said Ashleigh, adding that the majority of the collection is digitised, opening up scope for closing in on smallest details.

Ashleigh said most of the Aberdeen photos held in the George Washington Wilson Collection, haven’t been seen by the public.

Previous GWW exhibitions have concentrated on the Royal Balmoral and landscape side of his work.

“I think it is time they were seen,” she said.

“As part of my PhD, I am curating an exhibition using photographs from Aberdeen and Edinburgh.

“With the pandemic I’m rethinking how I do that, so it is most likely going to be a virtual exhibition now. Hopefully that will be ready by autumn this year.”

Ashleigh, who wants to become a curator after completing her PhD, wants people to recognise George Washington Wilson for the historical figure he is.

“He is not up there with Talbot, or Daguerre. His name crops up in history books but has never stood the test of time,” said Ashleigh, adding nobody really knew him outside of Aberdeen until his biography was penned by scholar Roger Taylor in the 1980s.

“It is so sad because he was revered across the world. He was internationally known, his work was reviewed by photographers and photographic societies as far away as Philadelphia and New York.

“I don’t think he’s received the recognition he deserves.”

Photographer to the British Empire

George Washington Wilson’s regal and dignified photographs of Queen Victoria at Balmoral are among the defining images of the Victorian age at its height.

Clearly, they enamoured the monarch so much, she bestowed a special honour on the Aberdeen photographer, to reflect the esteem in which she held him.

Ashleigh said: “Other photographers were given the title of photographer to the Queen, but GWW’s title Photographer Royal in Scotland was completely unique.

“GWW also had quite a close friendship with John Brown and he was permitted to use Monaltrie Cottage in the grounds of Balmoral Castle as a summer home.”

Wilson’s patronage by the royal family began in 1854 when he was invited to take their photographs in the grounds of Balmoral.

From his north-east home, where he was born in 1823, Wilson went to Edinburgh and then London in the 1840s to train as a portrait miniaturist.

He became established in Aberdeen in the 1850s as an artist and photographer, and quickly made a name for himself among the middle classes and landed gentry.

Ashleigh said Wilson’s success was thanks as much to the sense of business acumen he brought to his studio in Aberdeen as to his artistic talent.

She became fascinated by the photographer’s life and work when cataloguing images in the Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums collection while on placement for her Masters degree.

“He chose to live in Aberdeen because it’s close to where he was born in the parish of Forglen in the Turriff area,” she said.

“Having been brought up on a farm in rural Aberdeenshire he really appreciated Scottish scenery and the sights. Living in the city was not just a way for him to build a business, a life and a family, but also it was a gateway to the Highlands and this beautiful scenery he thought quite a lot of.”

George Washington Wilson and Co captured images from all over Britain, recording everything from Fingal’s Cave on the Isle of Staffa to the bustle of London’s Oxford Street.

From there, the firm’s reach extended across the British Empire.

Wilson had a staff of photographers including his son, Charles Wilson, who, with senior staff photographer Fred Hardie, toured the colonial townships of South Africa.

Sent to capture images of Australia in 1892, Hardie also travelled through Queensland, Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide.

These tours provide a vivid picture of gold miners and early settlers at work and play, and of the native or aboriginal way of life.

Ashleigh said: “The archival material the university has, with over 38,000 glass plate negatives, generously donated by Archibald Strachan in 1954, is such a rich repository of images that span the length and breadth of the British Empire.

“It’s not just the images taken by the man himself, but the images taken by his company and his sons and the photographers who came after them, after he died.

“The company he founded took the initiative and went abroad to the Mediterranean, Africa, Morocco, Egypt.

“They photographed a huge portion of the world.”

You can explore the George Washington Wilson Collection at the University of Aberdeen by clicking here