Slavery may seem to belong to another world but historians have argued it is closely tied to Scotland, and its legacy continues to be felt today. Ellie House found out more

When it comes to history, Scotland has never been afraid to face up to its bloody past and is proud of a rich heritage which continues to shape generations.

We are still able to explore the ruins where our ancestors once ruled and have fiercely preserved what is left of once glorious castles and fortresses.

But not many of us realise that some regular buildings we pass on a daily basis have a link with a more recent, shameful period of Scottish history.

It has been more than 200 years since the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act banished slavery throughout the British Empire, although there were some exceptions.

While many Scots campaigned against slavery, today not many people are aware that some cities, churches, industries, and businesses benefited from the African Slave Trade.

The misery and abuse which took place on sugar plantations may seem thousands of miles away, but slave owners lived across the UK, including in Scotland.

Some of the Scottish legacies of slave ownership in the British colonies are explored in the latest update to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, and researchers have spent months looking back at Scottish slave owners.

Contributors to the book include David Alston, who has spent more than a decade researching links between slavery and the Highlands.

To date he has identified 600 people from the Highlands with a connection to plantations before emancipation.

His most recent discovery is slave owner George Rainey, who was born in Sutherland.

“I started my research in 1999 and it has been an isolating task at times and a very personal journey,” said David, who is also a councillor in Inverness.

“Both myself and George are sons of ministers from Sutherland, and that’s a very strange feeling.

“Despite my research I never felt like I got to know George. By all accounts, he was a very cold, puzzling character.

“An awful lot of people in the church were actually linked to slavery in some way, which is incredibly uncomfortable.”

George, who died in 1863, attended Marischal College in Aberdeen. He was involved in the slave trade for more than 30 years, trading sugar and supplying credit to plantation owners in Demerara, which is now part of Guyana.

Following the emancipation, George received £50,000 in compensation for the loss of 1,000 slaves.

He then returned to Scotland and his amassed wealth had a huge impact on isolated communities and he quickly became known as a brutal land owner.

“He bought the islands of Raasay and Rona with the compensation money in 1845. He cleared one half of Raasay of people so he could use the land for sheep farming and he was pretty brutal in his methods,” said David.

Inhabitants of the island were forced off land they had farmed for generations.

For those who remained on the island, life was miserable and George ruled Raasay as if it were a slave plantation.

“One of his policies in Raasay was to forbid his tenants to marry, a measure of control reminiscent of the slave plantations,” said David.

“The wild Highlands conjures up a certain image of Scotland but there is a tapestry of slavery which has helped build our history, threads running all the way through that rarely get talked about.”

David believes there is only one building in Inverness which has acknowledged any link to slavery, although there are plenty that were built on the back of plantation wealth.

The Royal Northern Infirmary has a plaque stating that it was built on the back of profit made from plantations.

“England has been much better at recognising its link to slavery, particularly in places like Liverpool,” said David. “We’ve been pretty appalling in Scotland. When the Museum of Scotland opened in Edinburgh there was no mention of slavery – that’s shocking.

“I think there’s been a tendency in the Highlands to see ourselves as the victims, that’s a predominant narrative. We need to accept that we also victimised others, perhaps no more so than in slavery and that’s very difficult for people to come to terms with.

“People in both Cromarty and Tain objected to the emancipation of slavery because everybody benefited from its product in some way.

“People who had never been to the West Indies owned a slave, often through inheritance and marriage settlements.

“There is so much more work to be done when it comes to facing up to slavery.

“The way best to consider the impact it had and the objection to this abolition was that people couldn’t see a future without it.

“Everything was tied to slavery in some way.”

Many of Scotland’s country mansions also have links to slavery, including stunning Aberlour House, in Moray, which is now a primary school.

It was owned by Margaret MacPherson Grant, a philanthropist and sole heir to a plantation fortune.

Her uncle, Alexander Grant, amassed his wealth as a slave owner and sugar merchant in Jamaica and received £24,000 in compensation following the emancipation.

Margaret became hugely wealthy at just 20 years old but donated sums towards several good causes.

She donated £3,000 to pay for the building of a new episcopal church, St Margaret’s, in Aberlour, and in 1875 was the founding benefactor of the Aberlour Orphanage.

Researcher Rachel Laing who unearthed Margaret’s links to slavery, believes her legacy was used to do good, regardless of its origins.

“Margaret struggled with alcohol abuse and sexuality, problems it’s easy for young women to relate to today,” said Rachel.

“In other ways her difficulties were typically those of a 19th century woman – she talked of having a family and was fond of children but marriage would mean she had to give up her independence and forfeit her property rights to her husband.

“Her wealth made her very unusual and she benefited hugely from the social leeway it afforded her.

“I think it’s worth saying that she was a generous person, not just in her willingness to give money to a wide range of charities, but in her friendships too.”

Nick Draper, director of the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slave-ownership, also believes Margaret’s story demonstrates that the legacy of slavery was far reaching and incredibly personal.

“It would be wrong to say that modern Britain was founded entirely on slavery but it certainly made a contribution,” said Nick. “In many cases, and certainly in Margaret’s, it was the foundation of wealth.

“In some instances, there are very obvious symptoms deriving from slavery but not everyone is finely attuned to the legacy left behind.

“What is often the case in the study of slavery is that we tend to look at the enslaved as opposed to their masters.

“But the legacy of slave owners can be traced in localities and in buildings which we pass every day.”

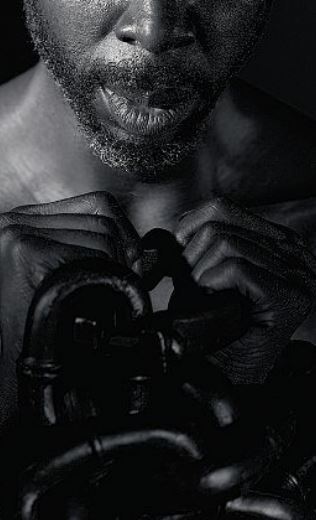

The Powis Gates, in Aberdeen, was built by Hugh Fraser Leslie in 1834 and features carvings of slaves.

The carvings stand as a nod to the source of wealth as Hugh Fraser Leslie owned several coffee plantations in Jamaica.

“The term ‘slave-owner’ itself was consistently avoided; most aimed to recast themselves as planters, proprietors, merchants, country gentlemen or statesmen,” said Nick. “Slave-ownership was an important source of their wealth but also informed their outlook, and the new work aims to bring this facet of British life into view.”

The stories of George and Margaret are not unique, but they demonstrate just how far-reaching slavery was. The new edition of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography was published earlier this month and is a national record of men and women who have shaped all walks of British life.

This edition has focused in particular on the economic, political, cultural legacies of British slave ownership.

Much of the work draws on data provided by University College London’s new Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slave-ownership. With each new discovery, researchers such as David and Nick continue to build a picture of a very tangible link between the Scotland of today and individuals who amassed wealth in slavery.

“I don’t think it’s for us to decide whether slave owners were good or bad people, but to see the imprint they have left,” said Nick. “Our aim was to resurrect and reconstruct so we can understand a piece of a much wider puzzle.”

Mr Rainy enacted a rule that no one should marry on the island. There was one man there who married in spite of him, and because he did so, he put him out of his father’s house, and that man went to a bothy – to a sheep cot.

Mr Rainy then came and demolished the sheep cot upon him, and extinguished his fire, and neither friend nor anyone else dared give him a night’s shelter. He was not allowed entrance into any house