“We got orders late the night before to stand to at 4.45am as the Germans were to make this attack. At about five in the morning the German bombardment started.

“I was in the front line, we were wearing our box respirators as they put over a great many gas shells which seemed to have very poisonous gas. I got a very bad dose of it which made me put up dirty green slime and was not able to keep on the SBR (small box respirator).”

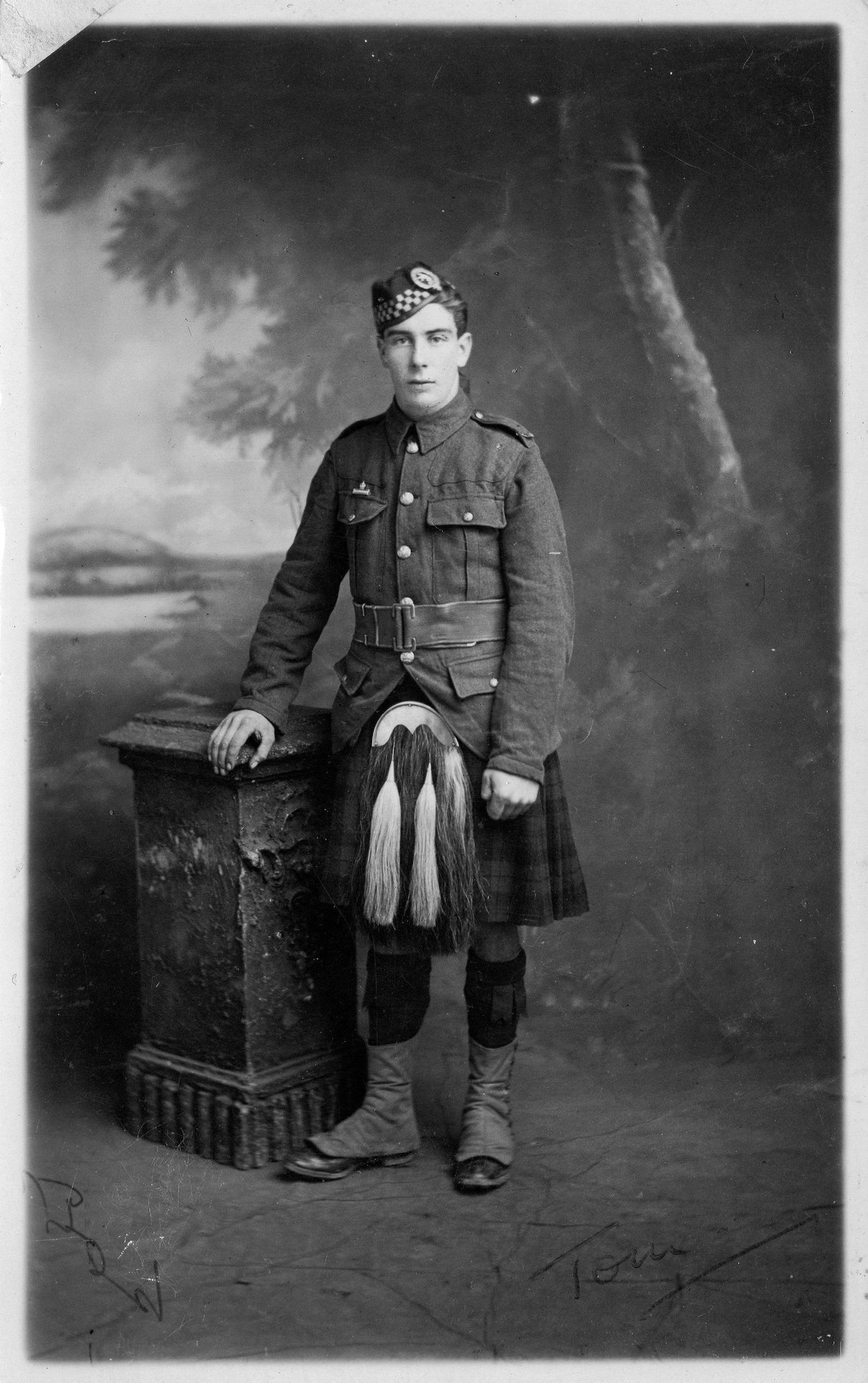

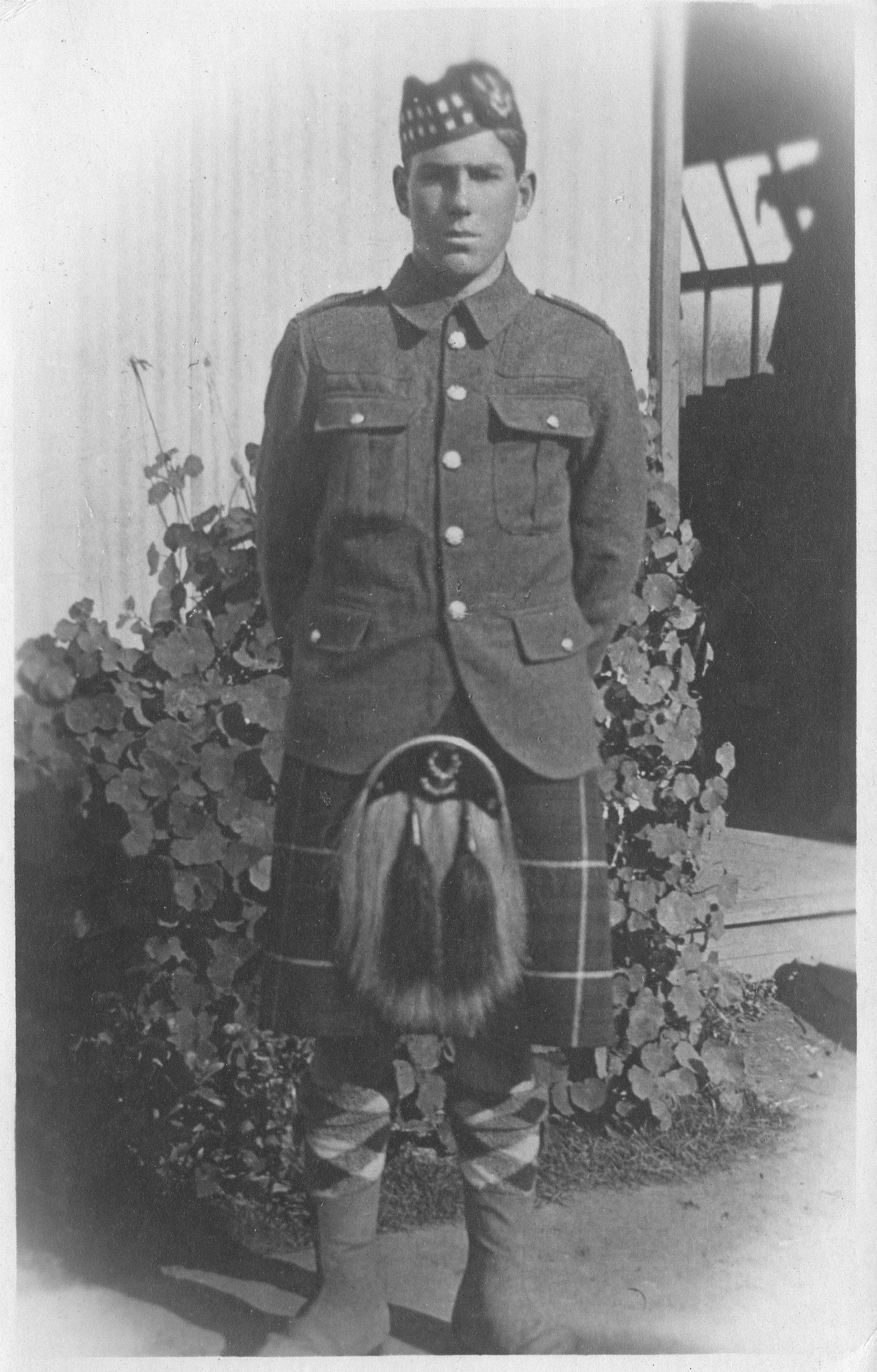

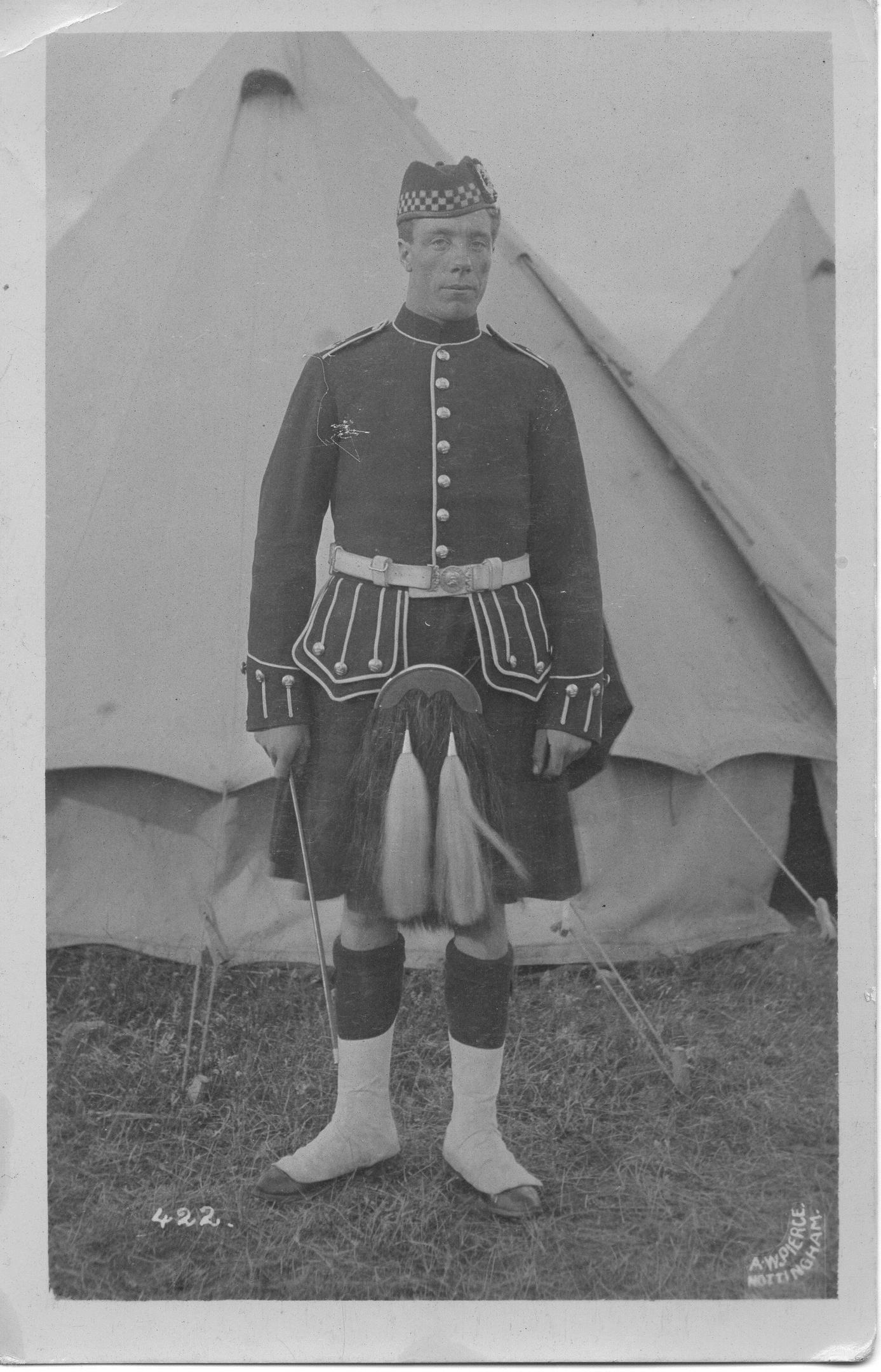

These are the words of Adam Mackintosh of the 5th Seaforths on March 21, 1918. His letters and diaries documented his wartime experiences in The Great War. Adam had been hit with chlorine gas, one of the poisonous gases the two sides used against one another.

Following this experience Adam was buried with a shell before finding his way to a dugout which acted as their headquarters.

“There were no doctors there and it was impossible to get to the dressing station so I had to lie there in a very bad state; or got a good nip of rum which made me put up more green stuff.

“Then I must have fallen off as I remember nothing more till I heard some bombs burst in the stairs of the dugout and some time after that when I did manage to crawl up the stairs, I saw that the Germans were occupying the trench so was taken prisoner.”

Adam’s experiences as a prisoner-of-war follow in his diary entries. They tell of poor living conditions and being given little food, and on some days no food at all. This was an experience Adam’s great granddaughter, Shona MacLeod, found out about when she delved into a box of letters years later.

“Adam’s experience as a POW, which he documented in a diary, was really shocking to me,” said Shona.

“Conditions were terrible, prisoners were so hungry they traded the clothes off their backs, their shoes, for potato peelings or a piece of bread.”

The process of doing a dissertation at university is one many of us are familiar with, but the amount of letters and information Shona discovered surpassed a simple document for her studies. Shona and Robin Reid have put together the memories of her family into a book, The Permanence Of The Young Men.

The book follows five men from two families in the north of Scotland: Tom Cameron, Hugh Cameron, John Cameron, John Hugh McIntosh and her grandfather Adam Mackintosh.

Adam was born and raised in Helmsdale, Sutherland, and, other than his travels during the wars, spent most of his life there. In the town there is a clock tower which serves as a reminder of the Highlanders lost.

He married Daisy Cameron 11 years after the First World War and the collection of papers was found when she died years later in 1981. It is from her that the letters from the Cameron brothers were sourced. Alice Mackintosh, Adam’s sister, also had a collection of letters and postcards which were passed down the family after her death at the age of 95, 14 years after Daisy.

The women and their families had to endure the tales of what their loved ones were living through. The letters are an accurate first-hand view of what life was like during the war. Hugh Cameron and Adam Mackintosh both wrote home about their eight months of training in Bedford.

Hugh wrote to his sisters on December 4, 1914: “We have just got in from church parade. This is all we have on Sundays. We usually go out at 6.15 for roll call other mornings and then get a drop of tea. Then an hour of physical drill from seven to eight.

“We were digging a trench in a field on Friday from 8.30 to 4pm. I was on the pick most of the time. It was awful hard digging. I have a few blisters after it.”

Shona studied at the University of Glasgow and worked on her dissertation for a year. The book itself took another whole year. She focused her material for university on the letters and diaries, before putting them into context with other literature she could find about the experiences of soldiers from the Highlands.

She said: “I was really intrigued by the seismic shift that the war had on their lives and the whole Highland way of life.

“Robin and his father Rab really helped me whilst writing my dissertation to put things into a wider historical context. The difference between my dissertation and the book is definitely due to Robin’s input as he put an enormous amount of time and effort into researching so he could really detail all the different battles where the men saw action, uncovering so much more about their time on the front that the letters could not, due to censorship.”

Shona credits Robin as the driving force behind the book. She believes he saw the potential for wider interest in the letters from her relatives. He helped to develop her interest in The Great War.

Families around Scotland – and other towns worldwide – received similar poignant letters.

They tell of a conflict which cost many men their lives. As the years pass in the papers, the war becomes longer, the casualty lists increase, diseases become more common and the tales become darker. A series of letters written in December, 1915, are to John Hugh McIntosh’s parents.

He was hospitalised with cerebro-spinal meningitis, which affects the brain.

Mrs MacIntosh received a letter about her son on January 7, 1916: “It has been but sad sad news I have been able to give you of your dear boy for the last week.

“After long trying to fight, he entered into his rest this evening at 7 o’clock.

“I feel his loss very much – and I know something of what it must mean to your husband and you. But you have much to console you by his death – and he was quite prepared to die.”

He died in France at the age of 18. A family legend, told by Adam Mackintosh’s daughter Maisie, says that the watch belonging to John was hanging on a wall and stopped the moment he died.

The journey of these men had a profound emotional impact on Shona. When she first sorted through the box of letters she put them in chronological order.

Then she was able to follow each man’s story. She found it very emotional to go from reading many letters sent by John Cameron to his family at home then suddenly a letter of condolence to his parents from one of his fellow soldiers.

Shona said: “I am really looking forward to what my granny, Maisie, will say once she has finished the book.

“It was difficult for me to let anyone read my dissertation as I am very sensitive and will never be 100% happy with anything that I write.

“I think she found the dissertation very moving because she found out so much more about her dad’s war experience, the intense hardships he endured which he didn’t really talk about.

“She said he was always so kind and gentle, you would never had known what he had been through. He joked to granny about eating raw potatoes on his birthday in the war but when you read his POW diary it really hits home, he was so lucky to survive the camp.”

The letters continue until 1939 and contain accounts of the front line, plus Adam’s time as a prisoner of war and the sad news of the deaths of John and Hugh Cameron and John Hugh McIntosh.

They died in France and are remembered by the monuments of that country and the granite clock tower in Helmsdale which acts as the war memorial for the area and the Strath of Kildonan.

Every time it chimes is a reminder of another life sacrificed.

John Cameron, Shona’s great uncle, died saving the life of Adam Mackintosh. After the war, Adam returned to Helmsdale and married Daisy, John’s youngest sister.

Shona said: “Granny said he always treated her like a queen. He only revealed to Daisy what her brother had done much later on in their marriage.”

The Permanence Of The Young Men: Five Seaforth Highlanders is available for £19.99 from www.capercailliebooks.co.uk