Tucked down a single-track road in the middle of the Spey Valley, Knockando Woolmill is a place where time seems to have stood still.

The nearby Knockando Burn babbles away cheerfully, with views for miles and miles of nothing but trees and farmland, slightly browned by the unusually hot summer.

Everything is just as it might have been a year ago, 10 years ago or even 100 years ago.

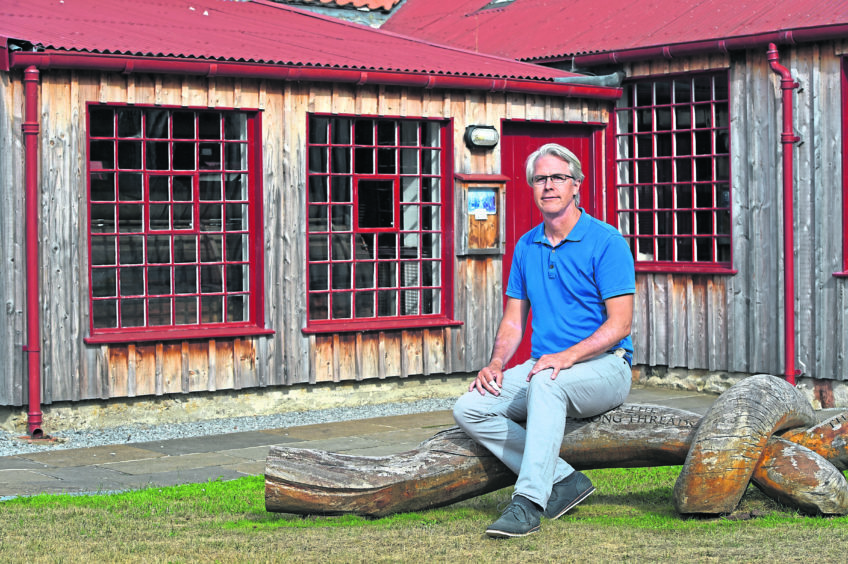

Bumping down the path to the mill, some quaint buildings well-hidden from the main road come into view.

A traditional granite cottage is first, followed by a series of timber and stone sheds with bright red tin roofs, looking rather incongruous in the rustic scene.

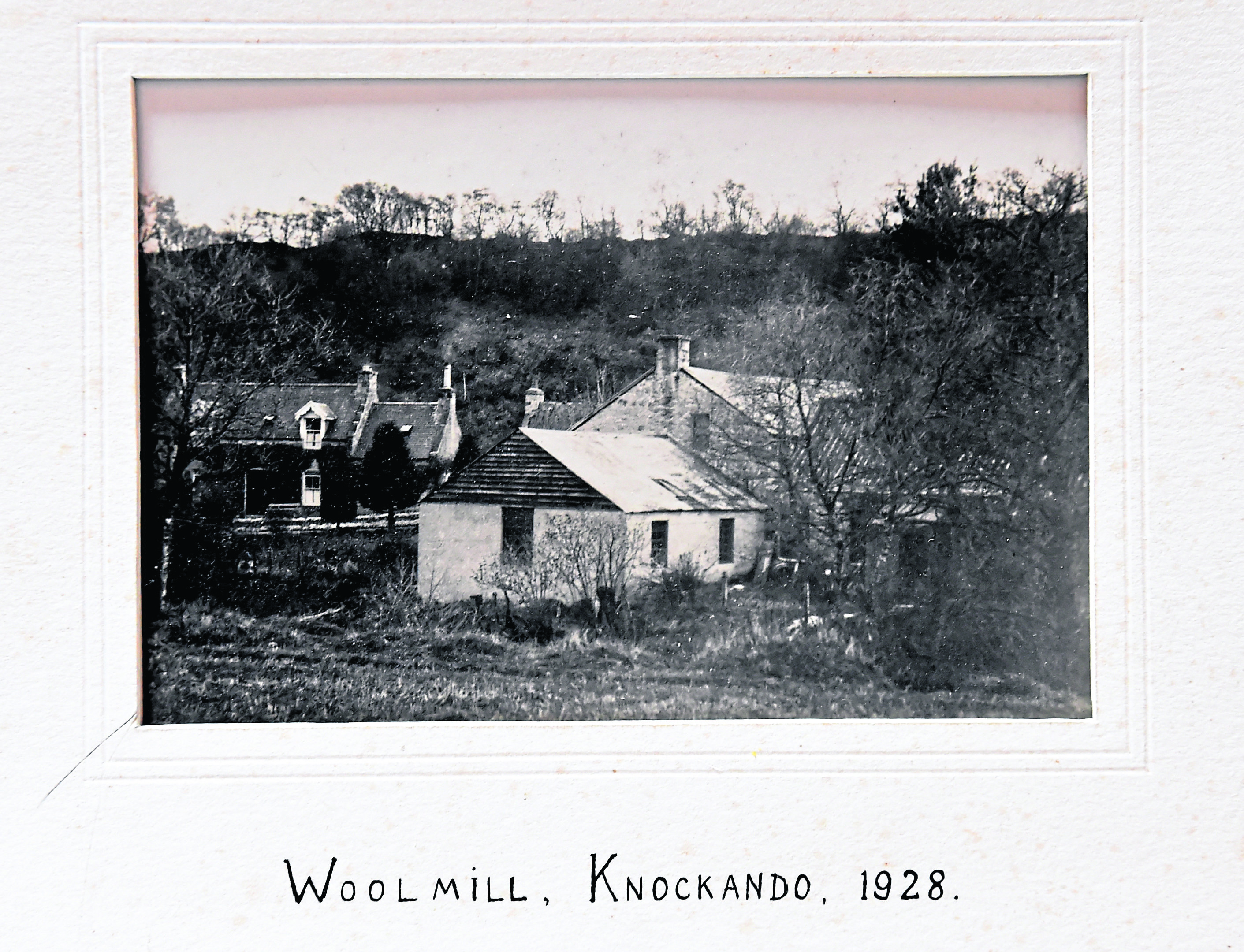

Spinning and weaving for more than 230 years, the Knockando Woolmill holds the prestigious title of being the oldest surviving district mill in the UK.

Things look to be in pretty good shape considering their age.

A cursory glance around might lead you to assume that things have always been this way, with the traditional buildings thoughtfully upgraded over the years.

Yet at the turn of the millennium, this mill was living on seriously borrowed time as ramshackle buildings leaned against each other threatening collapse.

Paint was flaking and the water wheel had long stopped turning as neglect began to set in on the old mill, which continued to produce textiles despite the crumbling surroundings.

“It was pretty much in ruin and was coming to a grinding halt in 1999,” said John Mulligan, manager of Knockando, “though no-one wanted to believe it.”

“The community of Knockando applied for the mill to receive Lottery funding, but unfortunately the bid failed.

“An unsuccessful appearance on the BBC’s Restoration programme was also a blow.

“In the meantime, the site wasn’t getting any younger and the signs of age were really beginning to show.

“So 2000 the Knockando Woolmill Trust was formed with the aim of restoring the buildings and machinery, and the organisation spent 10 hard years raising £3.5 million needed for the project.”

By 2012 most of the refurbishment work was completed, though great care was taken to ensure that rich history of the mill wasn’t overshadowed by the renovations.

Originally part of a small croft, the woolmill was passed down through generations of families who worked the land as well as carding, spinning and weaving with local wool.

It is first listed as the Wauk Mill in parish records from 1784, when the Grant family was listed as the owners of the property.

“We know it’s been running for longer than officially recorded,” said John.

“But the reason we have the date 1784 is because the Grant family christened their son in a church nearby and listed their address as the mill.

“William Grant cited his occupation as ‘prepping the cloth’, but this work was likely just to supplement the money he earned from farming.

“There would be little work carried out in the mill during sowing or harvest time, but after shearing, local farmers would bring in their fleeces to be processed and take them away as blankets and tweed.

“Then eventually it seems the mill became more successful than farm work and took over as the Grant’s main source of income.”

From then on the mill changed hands a few times, often being passed from father to son.

When times were good, the woolmill tenant would buy a new (usually secondhand) piece of machinery and extend the mill building just enough to keep the weather off.

Yet being thrifty farmers, doors and windows weren’t seen as a priority, resulting in a collection of tiny ramshackle buildings stuffed full of historic machinery.

“During the First World War the mill set about making hundreds of blankets to send to the troops,” John said.

“Production increased hugely and a drying shed had to be built for the blankets to be finished even in the coldest weather.

“From there things were pretty quiet until the 1970s, when the old man who was running the mill put it up for sale.

“There wasn’t much interest though, as even then producing tweed and tartan was seen as an outdated profession.

“Then, quite by chance, Londoner Hugh Jones arrived at Knockando in 1976 while on holiday in the Highlands.”

Hugh would go on to change the course of history at the mill, though when he set foot over the threshold at just 23 years old, he didn’t yet know it.

Charmed by the mill and its history, Hugh stayed to learn the traditional processes and skills necessary to both use and maintain the machinery.

Soon he took over ownership and single-handedly kept the mill alive for 30 years, weaving on an old Victorian loom every day.

However, as time passed and Hugh’s 60th birthday approached, he conceded that the time had come for some serious restoration work at the mill, and allowed for the trust to be set up.

Over the next few years the mill was successfully transformed from a crumbling shell to a fully functioning business ready for modern day textile production, yet another and altogether different question inevitably arose – what next?

It’s a familiar tale across Scotland, where mills have been revamped or closed and specialised skills built up over generations have been lost.

For Knockando, it has taken a lot of careful thought to preserve the historic practices while at the same time attempting to run a prosperous business.

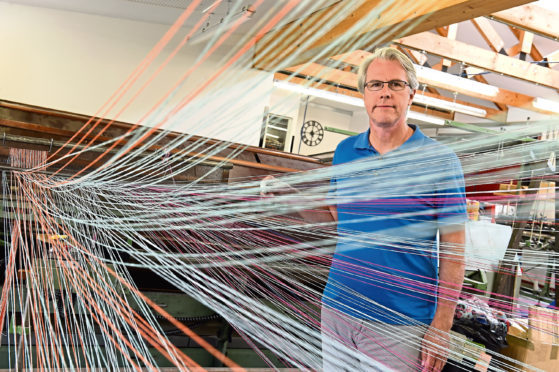

Great hunks of Victorian engineering with their wheels and cogs now sit alongside more efficient, modern equipment, with both sets of machinery fired up on a daily basis.

“We’ve always produced tweed and tartan here for local estates and members of the public, but there is only so much tweed and tartan you can buy,” said John.

“And nowadays we are competing in a world of cheap, throwaway fashion and so needed to move the mill into the 21st century.

“So today, although we still use machinery dating from 1870, we also have more efficient, modern devices and have recently introduced computer design software for the first time on our very newest designs.

“It’s becoming harder and harder to find people who want to learn on the historic equipment because career progression today takes them in a more modern, different direction.

“It can feel like a step back in time for young people to come to Knockando so we are thinking about starting partnerships with universities for students to join us for a semester to pass along the knowledge of these old looms.

“Recently we also ran a competition for graduates to have their woollen designs made in the flesh which was hugely successful.

“But we do struggle in the off-season, as the mill is closed to the public over the winter.

“We are starting to generate sales on the internet to counteract this, but it’s a work in progress.”

Yet despite his concerns, John is quietly hopeful for the future of the mill.

“Fashion is starting to move towards sustainability and traceability,” he said.

“Local fleece and wool is what young professionals are looking for, particularly when you can come and visit exactly where it is made.

“I can tell you that Ballindalloch Estate wool is going through the machine as we speak, which comes from sheep two fields away.

“It adds something different to the garment when you know that information, and it’s totally different to picking an anonymous piece of tartan up from a tourist trap on the Royal Mile.”

It’s easy to get swept up by the romanticism of Knockando – the landscape, the history, centuries of traditional skill being saved.

But John sums it up rather succinctly.

“You know when you go on holiday and bring back a bottle of that local drink you liked when you were sitting on the beach?” he said.

“Somehow it’s never quite the same when you get home.

“At Knockando we want to create something people will be happy to wear when they get back, wherever they are from, and something they can enjoy for years to come.

“We are not men in suits down in London who sit in front of laptops drinking lattes.

“We are a working mill day in, day out and hopefully always will be.”