Scotland’s first super hero is here to save the day. But don’t turn him into a political tool – he’s got bigger fish to fry

At a time when Scottish national identity has never been so ferociously debated, it’s perhaps fitting that into the fray has bounded the country’s first super hero.

Saltire, a big, blue and ginger mountain of an immortal man, forged in the fires of the mind of Scottish writer, John Ferguson, burst on to the comic book scene late last year, and has already proven a hit with fans of the super hero genre.

“Saltire is quintessentially Scottish in his visual appeal,” explained John of his Caledonian creation.

“He’s immortal and he was created rather than born, so he has always been a super hero, and doesn’t have an alter-ego. He was created to protect the land of Scotland in pre-history, and he represents the notion of Scotland and protects it from any potential invasions which have happened many a time throughout our history.”

You would be correct for thinking Saltire is ideal fodder for Alex Salmond’s pro-independence campaign, but that’s not the aim for John and his team at Diamond Steel Comics, who operate out of Dundee. While flying the flag for Scotland is absolutely part of the deal, no intentional underlying political messages pervade the comic series’ pages.

Though John admits, with the September 18 referendum just round the corner, it’s difficult not to be dragged into the conversation when your creation is the very embodiment of all things Scottish. Nothing is off the table when it comes to the debate.

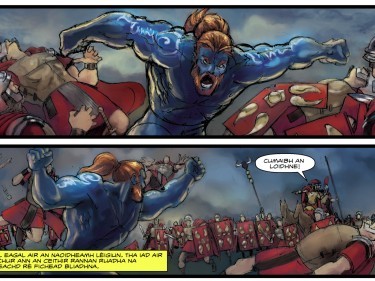

Earlier this week at the Edinburgh Book Festival, Saltire further stirred up Scottish patriotism when his adventures were officially launched in Gaelic, thanks to the skills of Inverness translator, Raghnaid Sandilands. With a second graphic novel coming later this year and translations in Scots also being considered, Saltire’s appeal is being opened up to Scottish readers in all corners of the country.

But just what can a hulking representation of Scottish patriotism tell us at this critical juncture in our national identity?

BATTLING THE TARTAN CRINGE

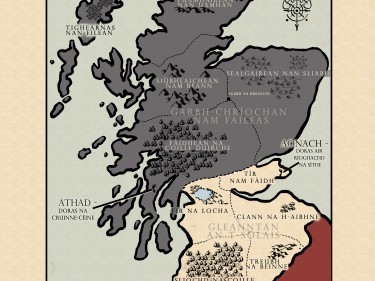

A good place to start is to consider the inspiration behind Saltire’s genesis. Set in a pseudo-historical Scottish landscape, the series reimagines pivotal moments in our country’s history, kicking off with the incoming invasion of the legendary ninth legion of the Roman empire. To save themselves from the imminent onslaught, the many clans from the north and south of Scotland come together to invoke their immortal hero who was first created by ancient magic in the pre-historic era – Saltire.

It might sound a bit corny on the face of it, but with the dark and brooding artwork, and beautifully lyrical writing, the series clearly isn’t playing for laughs. John explained that a strong motivation behind the story is to counteract what he calls the “Tartan Cringe” – the innate Scottish sensibility of putting ourselves down, and shying away from the stereotypical emblems of Scottishness, bagpipes, Scotty dogs and all.

“We thought, ‘let’s take all these elements that we’re known for, such as being so pale that we’re blue, and all being ginger and hairy, and let’s give him a ginger beard and hair’. So we’re now calling it ‘Tartan Cool’ rather than ‘Cringe’.”

The sincerity with which the material is treated is part of John’s rallying call for us to reclaim our pride.

“If we were going to make a Scottish superhero world, we needed to take it seriously. Because people in Scotland will be expecting a joke or a derisory version. People were expecting it to be another Bananaman or Supergran, and it’s not. And that’s partly why he looks the way he does, kind of iconic.”

The second main inspiration behind Saltire springs from John’s own passion for Scottish history and mythology – a passion and knowledge-base which he finds isn’t necessarily instilled within Scots these days.

“People learn a bit of history at school, such as Bannockburn and so on, but we don’t know our own mythology. I really like investigating Gaelic, Scots and Pictish mythology, so I thought ‘wouldn’t it be great to bring that into a more modern form like in a comic book, and into something that’s more dynamic like the superhero genre?’”

Reading the comic isn’t a substitute for a history lesson though. Far from it. As John indicates, Scottish history is often vague, and so this opens an opportunity to fill in the gaps by combining fact, mythology and imagination.

“If people read the Saltire books from a historical perspective that would be terribly wrong. But then again, it might get them interested in the history of the country. I personally find it far more rewarding by looking at what might have happened. It gives it a more legendary feel. A Tolkienesque feel more than traditional super hero stories.”

THE UNDERDOG STORY

Looking beyond the fantastical elements, Saltire begins to take on a more real-world tone when you to scratch below the surface. Like all cultural products – books, films, television series – graphic novels can tell us a lot about the societies they have sprung from.

For John, Saltire isn’t only set apart from his super heroic brethren by being the first Scot. He also hails from a very different ideological standpoint. And it all comes down to the fundamental make-up of Scotland’s history.

“I love Batman, Superman, the Avengers, but they’re all imperialist figures,” he said. “They come from big republican-based countries where essentially the norm they are protecting is right-wing capitalism. Now, there’s nothing wrong with that. But it’s just, as long as the stock market is spinning round and the world is making lots of money, that’s just their norm.

“But the Scottish story is more left-leaning and the history is not one of invasion. So you don’t need to justify Saltire’s actions – he’s not invading people, he’s just protecting them.”

The fact that we have been invaded multiple times – by the Romans, Vikings, the Saxons and English, to name a few – has set our own cultural mythos on quite a different path, John argues.

“From a storytelling point of view, you are telling the underdog story, and that’s the part that human nature likes. In my opinion, that sells better than characters like Judge Dredd who is a big crazy fascist. Even Batman and Superman defend something that is western and right-wing in its political stance. They are protecting people in an ideology that a lot of people in this part of the world don’t agree with.”

THIS ISN’T A MANIFESTO

This might sound like political messages are woven into the tales of Saltire’s heroism after all. But that’s certainly not the case or intention, John said, though he understands why many fans of the series see Saltire as something of a symbol for independence.

So how do he and his team position Saltire within the wider debate?

“We let the conversation happen. We don’t stop it but we’ll never stick a Yes badge on him,” he said.

“Yes, it’s patriotically Scottish in the same way as Irn Bru is. That doesn’t mean we’re going to do a disservice to people’s political beliefs. We live in a country which is making a democratic political decision next month and comic books are not where that fits.”

But how about the team personally. Where do they stand on independence?

“We have an opinion on (independence) because it affects the creative industries, and we think they’re not really where they should be. But we don’t look at Saltire and make it about standing on one side of the political spectrum. Yes, as individuals in the company we have our own opinions, and being patriotically Scottish we lean more one way than the other, as do many of our readers.”

In fact, Saltire has a lot of no-voters among his fans – some who have even contacted the Diamond Steel team to express their enjoyment of the tales, but that they would still be voting against independence.

“We just say, ‘This isn’t a manifesto. It wasn’t meant to change your mind. It’s just a superhero comic’,” he said laughing.

With seven more century-spanning Saltire stories already planned – each likely to take six months to publish – one thing is assured: Saltire’s reign with go far beyond the political landscape of the day. After all, he is immortal.

For further information on the Saltire series, visit www.diamondsteelcomics.com

SALTIRE: CHAMPION OF THE GAELIC LANGUAGE

“I was initially overwhelmed. There’s a lot of drama and it felt like a whole other way of speaking,” Raghnaid Sandilands told me of her first impressions of the Saltire series over the phone from her home in Farr, near Inverness.

The Balmacara-raised, former manuscript curator, was approached by the Gaelic Books Council to translate the super hero’s first graphic novel, Saltire: Invasion – launched this week in translated form as Saltire: Ionnsaigh. Translating was nothing new to her, having already translated Asterix and the Picts in 2013.

After some initial trepidation about tackling Saltire, she jumped at the chance. She knew then that to find the right tone for this modern legend, she would need to take a step back in time into the realm of ancient Celtic mythology.

“To give it some swing, I went back to place poems and stories to get inspiration. There are plenty examples there about heroes and warrior chiefs, such as in the Ossianic poems. I had to make sure it lifted off, and had authenticity,” she explained.

Speaking later to John Storey, head of literature and publishing at the Gaelic Books Council, I learned that Gaelic fiction has undergone a resurgence in the past 10 to 15 years. He noted that more Gaelic novels have been published in the 21st century so far, than was published in the entire 20th century.

In the latest development of this resurgence, the Gaelic community has been quickly warming up to the idea of reading graphic novels in their native language, with adventures of Asterix and Tin Tin having been published in a book apiece in the past year – and selling out within a month.

Saltire, however, is quite a different proposition, with a potential to straddle multiple marketplaces.

“There’s the schools market, but there’s also the general readership, as well as Gaelic readers who are into graphic novels,” Mr Storey said.

“So you might think it’s a narrow, specialist and quite limited readership, but it could be quite broad because the character is so vivid.”

As with the topic of independence, Gaelic is a similarly contentious subject matter. Is it a dying language? If only 60,000 speak it in Scotland, is it over-subsidised? Such questions continuously are regularly debated in local and national government fora.

John Ferguson understands Gaelic’s position as an on-and-off political hot potato.

“It’s dreadfully political to talk about Gaelic because the reasons it’s not spoken about, again, are political, especially at the moment with everyone being red-eyed in referendum fury,” he said.

“We try to stay out of it, because we just make comic books. At the end of the day, we’re making something Scottish so some people will of course bring up politics.”

Irrespective, he feels strongly in Gaelic’s continued value in Scottish society, and that Saltire is ideally positioned to champion the cause.

“Bringing Gaelic back is important to the Scottish psyche. Because we were never asked if we would have wanted rid of one of our indigenous languages or not. So that’s partly why we’ve done this, to say ‘here’s an option for you, – these are the things you could know more about your country, in terms of the history, mythology and languages of it’.”