As summer hots up, increasing numbers of folk are stripping off and diving into lochs, rivers and seas all over the country.

The concept of open-water, or wild swimming, is nothing new – we’ve been doing it for centuries.

But as we ease out of the Covid pandemic, the idea of splashing around in the cold, life-affirming waters of Scotland seems to have increased its appeal.

What indeed could be more liberating, especially in just a swimsuit, bikini or pair of trunks?

Those daunted by the prospect of swimming in the open sea, with its associated hazards (undercurrents, rip tides and so on), are embracing the prospect of being able to bathe in coastal tidal pools.

Sadly, most sank into decline decades ago, falling out of favour with swimmers who were lured away by the warm water and sunshine offered by foreign holidays.

In response, many councils closed pools, citing dwindling attendance and crippling refurbishment costs.

But with the recent obsession with swimming outdoors, and nostalgia for a time when summers were spent enjoying the Scottish coastline, there’s been a huge resurgence of interest; folk are keen to see their once-loved tidal pools being revived.

Already, in Caithness and the East Neuk of Fife, a few have been brought back from the dead and are up and running thanks to the efforts of passionate and dedicated community members.

North Baths

A group of around 20 people swim at North Baths in Wick on a daily basis.

They’re in the process of seeking funding to restore and refurbish the baths, which were in a dire state until recently.

Originally opened in 1904, the baths were a mecca for locals for 60-plus years… until they abandoned them in favour of indoor pools.

Local historian Harry Gray recalls how they lay “in total devastation” in 2003.

In 2005, he and a group of fellow pensioners got together to restore the site, but recent winter storms undid their hard work.

Patty Coghill swims in North Baths most evenings and is involved in the restoration project.

“When I swam there with two cousins in February, it was in a really sorry state,” she laments.

“It was tricky getting in with all the boulders and a concrete plinth which had been smashed and thrown into the baths in 2012.

“One of the main walls was undermined and didn’t look like it would last another winter, which could result in the baths being lost forever.”

Despite the hazards, the trio enjoyed their wee dip and became addicted to swimming there.

After a photo of them was posted on Facebook, Patty was inundated with messages from folk keen to join her.

That inspired her and two friends to launch Kool Water Swimmers (KW1), which describes itself as a “friendly and casual swimmer/dipper group”.

Members post regular updates online about meet-ups (at North Baths, along the coast at Dunnet Beach and beyond, and special sunrise and sunset dips), and invite folk to help out with maintenance work, whether shovelling sand from the baths – “please come with a rake or a spade” – or fundraising challenges.

“The ball is rolling to save the baths and temporary repairs will bide us enough time to raise the £15,000-plus needed to do proper repairs,” says Patty.

“When we emptied the pool, we found an old bike and an old shell from the Second World War!

“But it’s a magical place. There’s a small section that we call our ‘infinity pool’ and the view is amazing. There’s also what feels like a spa where the natural rock is tiered.

“There are so many health benefits to swimming in cold water and it’s great to bring people together after the awful year we’ve had with Covid.

“I doubt very much I will go back to an indoor pool, sea swimming or a chlorinated pool.”

KW1 co-founder Claire Mcgovern adds: “We really enjoy the buzz of being in the water – you’re guaranteed to come away from a dip with a smile on your face and a wee spring in your step.

“We want to encourage anyone with a niggle of inquisitiveness to give it a go. We’re a friendly, fun bunch of like-minded folks keen to welcome new people.”

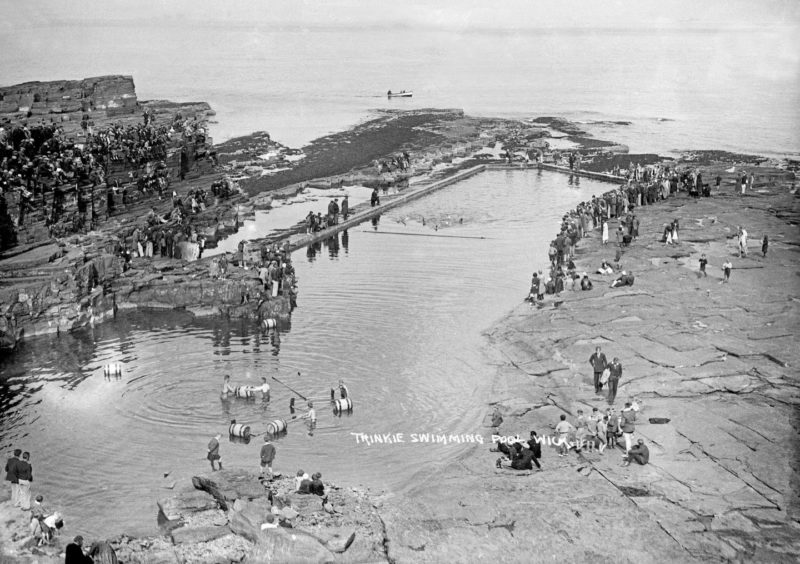

The Trinkie

Also in Wick, a group of volunteers is stepping up efforts to reinstate The Trinkie, a natural rock pool which was a popular hang-out for swimmers until a few years ago.

The Trinkie Heritage Preservation Group is on a mission to save it from crumbling and return it to its former glory.

It was badly damaged in a storm a few years ago and the group is in the midst of raising the £20,000 needed to do repairs.

Secretary Catherine Patterson learned to swim in the Trinkie, as did generations of locals.

“People have fond memories of The Trinkie and still go there to explore the rock pools,” she says.

“Families have socialised there for decades and we want to restore it to celebrate its historic role in the area.”

Tarlair

Meanwhile, at Tarlair pool in Macduff, Banffshire, efforts are being made to breathe new life into the once-popular and now deteriorating venue.

Built in 1931, the Art Deco pool, with toddler pool and boating pool – which once boasted a tea pavilion and changing rooms – was granted A-listed building status by Historic Scotland in 2007.

As holidays abroad became cheaper in the 1970s, visitors dwindled and the decision was taken to close.

The site was never wholly out of public consciousness, and hosted all sorts of events, reinventing itself as a unique venue for open-air concerts.

In 1994, Runrig and Wet Wet Wet played at Tarlair as part of an annual festival, hot on the heels of Jethro Tull and Fish in 1993.

The pavilion closed in 1996 and is being passed from Aberdeenshire Council to the Friends of Tarlair group, established in 2015 to rejuvenate the site.

In 2015, the council repaired the boating pool, toddler pool and terrace to the tune of £300,000 and the Friends group is applying for funding for more repairs.

They were delighted when Greenspace Banffshire, in tandem with VisitAberdeenshire, recently planted 420 trees around the site, with help from locals including a chap in his 90s.

Chairwoman Pat Wain says the iconic structure is steeped in history and hopes it can be redeveloped.

“A great local sense of identity remains, even in its semi-derelict state,” she says.

“We’ve formed links with the Macduff Marine Aquarium, Coastal Paths Forum, Banff Business Forum, wild water swimming groups, Banff Countryside Group, Macduff Primary School and VisitScotland, who see Tarlair as an exciting new product.

“It sits well with tourism in the area, including the North East 250 route and potential visits when cruise ships dock in Aberdeen.

“Our hope is that the big swimming pool can gain funds for repair soon after the pavilion – the final stage to restoration.

“Continued fundraising, and the proceeds from the pavilion business will be needed for ongoing maintenance.”

Portknockie

In Moray, locals faced with the loss of the small 1950s tidal pool at Portknockie raised almost £30,000 for repairs to ensure its survival.

Donna Coull organised the fundraising events with friend Lilian Urquhart.

And while her daughter Kirsty Farquhar and husband Steven take care of the majority of the maintenance, they’re bolstered by a team of helpers, one of whom is 83.

“Ten years ago Moray Council decided to hand over the pool to the village or fill it in,” says Donna.

“At that time a group of paddling pool users took it over and maintained it, cleaning and painting it.

“But about four years ago we noticed it was leaking and walls had started to break so Kirsty, Lilian and myself started a major fundraising campaign to get our beautiful blue pool repaired.

“It was really busy last summer and it’s great to see.”

Portsoy

Portsoy in Aberdeenshire boasts a very sorry looking tidal pool but some brave locals do risk using it.

It was closed in 2001 because it failed to comply with health and safety legislation.

Councillor Glen Reynolds says while the cost to bring the pool back to a safe usable standard would be considerable, he would support plans to restore it, if there’s a demand.

“People would need to be aware of a plethora of safety and insurance issues, but with the right funding it is possible,” he says.

“It’s a beautiful stretch of the coast and post-Covid, for health and wellbeing as well as a fun day out, this is exactly the sort of outdoor activity which should be considered.”

St Monans

The tidal pool at St Monans in the East Neuk is a haven for “safe” outdoor swimming, with little chance of being swept out to sea.

It’s in an idyllic location; the windmill which once pumped sea water into the long-abandoned salt pans standing proud on the raised beach above.

Hewn out of the rocky coast, the pool is ringed by man-made walls and access points which naturally replenish with a fresh cascade of seawater.

It’s thanks to a huge community clear-up spearheaded by Jennifer Jones that the pool is once again thriving and used by around 50 people on a daily basis.

Prior to February, it hadn’t been maintained for 40 years and was full of lurking hazards such as broken glass and chunks of rusty metal.

“It makes me happy to see a pool that’s been left to rot for so long being used again,” says Jennifer.

“Nobody had swum in it for 40 years, but now there are people enjoying it, both in wetsuits and just swimsuits, who would never have dreamed of going in.”

Even though the pool has been cleared, it’s not officially maintained, so people use it at their own risk.

Pittenweem

Along the coast at Pittenweem, the West Braes Project secured £270,000 of funding to restore the sea pool to its former glory.

The historic pool was a huge draw for families before it fell out of use in the 1980s.

In its heyday it had a chute, a diving board, a float in the middle, a cafe and a row of wooden changing rooms.

Locals and groups have been enjoying the pool since its unofficial opening on May 8, with a grand launch event planned for August 7.

West Braes Project trustee Bill Watson said while records of a pool in Pittenweem date from 1895, the pool “as it looks today” dates from just after the Second World War when it was rebuilt and refurbished by locals.

“We’ve been applying for funding to restore it for about five years,” says Bill.

“A crazy golf course, dating from the 1950s, was restored and opened five years ago to provide some funding and since then the main focus has been the tidal pool.”

The hope is that pool users will offer a donation, however small. This will help with plans to erect interpretation boards, a viewpoint, cafe, sensory garden, and ultimately an information centre.

Julie Brooks is a member of the Menopausal Mermaids group which regularly swims in the Pittenweem pool, all sporting signature flowery hats.

She describes it as an “infinity pool”, adding: “You can’t see where it ends and where the sea begins.”

“The pool always looks stunning, particularly at sunset and sunrise, as you can see all of the colours of the sky reflected in it,” she muses.

“Although you’re swimming in the sea, the pool is a safe haven.”

The group even has an honorary merman, Robert Melville.

“He started out as our ‘bodyguard’ and official photographer, but eventually we persuaded him to swim with us!” says Julie.

“He refuses to invest in a flowery hat but has a variety of brightly coloured swim caps.”

The Bathie

Inspired by the Pittenweem and St Monans projects, a group formed to clean up Cellardyke’s sea pool, fondly known as “The Bathie”.

Locals have been grafting hard, working to clear it of debris, seaweed, rocks and chunks of concrete.

The makeover project is still in its infancy, with funding being sought to restore the facility.

The fact it’s not yet been renovated hasn’t stopped folk from enjoying a wee dook and it’s recently been awash with swimmers, kayakers, canoeists and paddleboarders.

Eugene Clarke, clair of Cellardyke Bathie Group, says while the pool, which was built in the early 1930s, was once hugely popular, it fell out of use in the late 1970s “as a result of folk spending holidays in the likes of Torremolinos”.

“The pool was owned by the Crown Estate who leased it to Fife Council for about £500 a year,” he explains.

“One condition was that if the council gave up the lease they would have to restore the whole area to its original natural condition, a requirement so absurd even the council didn’t go for it. Instead they bought it last year for £1.”

Local woman Christine Wilson was behind the project to restore The Bathie, forming a group to help clean it up.

“I spent a lot of time there last year and saw how much it was used but how dangerous it was to access.

“A survey revealed 150 people wanted to see it restored to its former glory.”

When Christine first posted on Facebook calling for help to clean up the pool, 30 people turned up.

“A lot of elbow grease and muscle has gone into this, with one guy spending weeks shifting stones with his wheelbarrow,” she says.

“There’s also a fab wee baby pool that needs sorted. Safe access is top of my list. But it’s lovely to see around 20 people using it daily.”

Many hands make light work and Christine is encouraging others to get involved: “Everyone is welcome to pop along to help – for five minutes or five hours!”

Long-term, the plan is to fully restore the pool with diving boards, family-friendly facilities, and possibly showers and shelters.

“The Bathie project has brought the community together,” reflects Eugene. “It’s a place people get misty-eyed about. Folk recognise it as a valuable community asset.”

Castle Sands

Despite not being maintained in years, Castle Sands in St Andrews is used on a daily basis, with numbers of swimmers rocketing since March 2020.

Journalist Nora McElhone has found swimming there “something of a sanctuary” in the past year.

“The old tidal pool has become a more popular spot since last year but it’s pretty dilapidated and needs to be cleared of sand, rocks and seaweed,” she says.

“It’s been inspiring to see the work being done by other communities to revive their tidal pools and who knows, perhaps we could follow their lead with a similar effort.”

FACTFILE

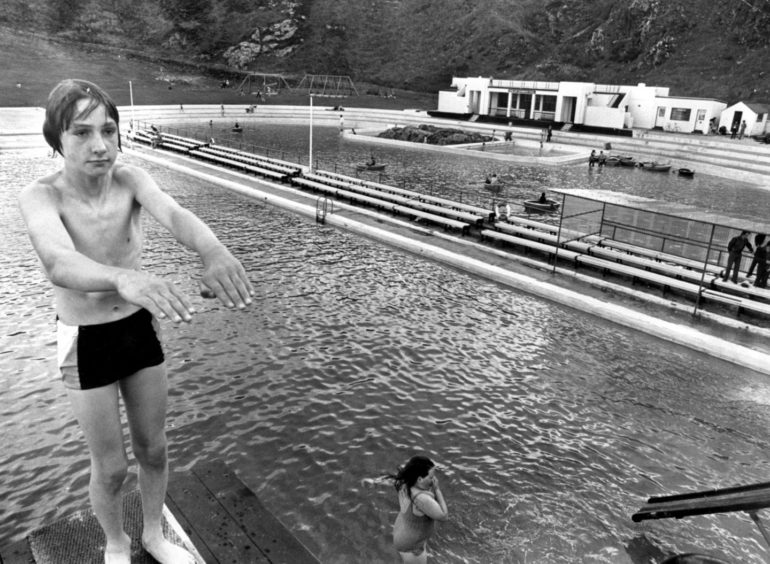

Generations of brave souls learned to swim in Scotland’s coastal tidal pools, long before heated and indoor versions were invented.

Hugely popular among Victorian and Edwardian swimmers, they cropped up along the coast, from Scalloway in Shetland, sadly bulldozed to make way for a car park in 1993, to Powfoot in Dumfries and Galloway.

Far more modest than lidos, boasting heated pools such as at Stonehaven and Gourock, tidal pools emerged from rocks, were supported by manmade walls and access points, and replenished naturally with seawater.

They offered little in the way of safety features, often being accessed by a set of slippery steps and a rusting handrail.

The lack of water filters meant swimmers often came face to face with seaweed and debris.