The fishing villages of the north-east are held in great affection by many, the memories shifting in the sand.

The coast still plays a massive role in our day-to-day life, as proven when your life recently did a coastal takeover – covering everything from making a living underwater to raising a family by the sea.

But it is the glistening shallows of the rockpools, the families who once lived side by side for generations, and a seafaring way of life which truly captures the heart.

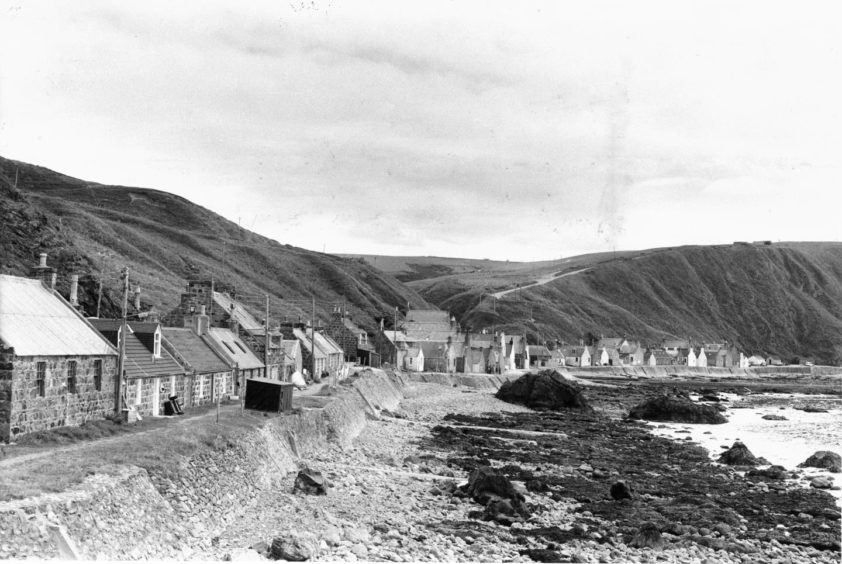

Crovie does not have to try hard in capturing such nostalgic longing, perching as it does on an almost impossibly narrow ledge between the base of cliffs – which form the east side of Gamrie Bay – and the sea.

These days it is mainly day trippers as opposed to true locals who frequent Crovie.

And yet this rocky outcrop was once a thriving community, as marine biologist Jim Watt Treasurer, can testify to.

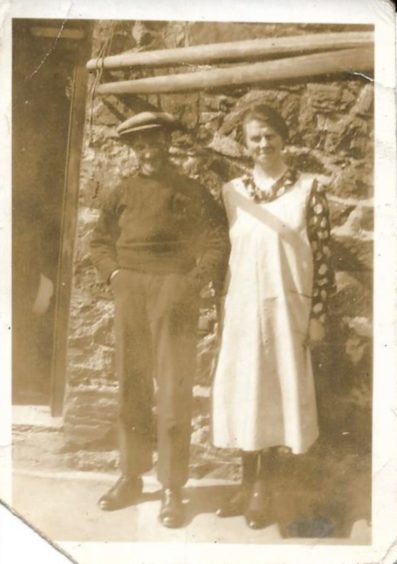

He stayed in Crovie with his grandparents during the Fifties, and has shared both precious memories and photos of what life was really like in this magical place.

Here is his eye witness account of what he describes as the lost herring fishing community.

Jim Watt Treasurer

How well do we remember our childhood or early years?

There are definite defining moments that stay with us and are etched like tiny tapestries in our mind.

As the years go by, does our memory fade or does it improve?

Crovie (“Crivie”) is one of the best-preserved fishing villages in Scotland. It nestles under green braes with a view over Gamrie Bay in front.

When the sun shines, the bay is a glowing jewel.

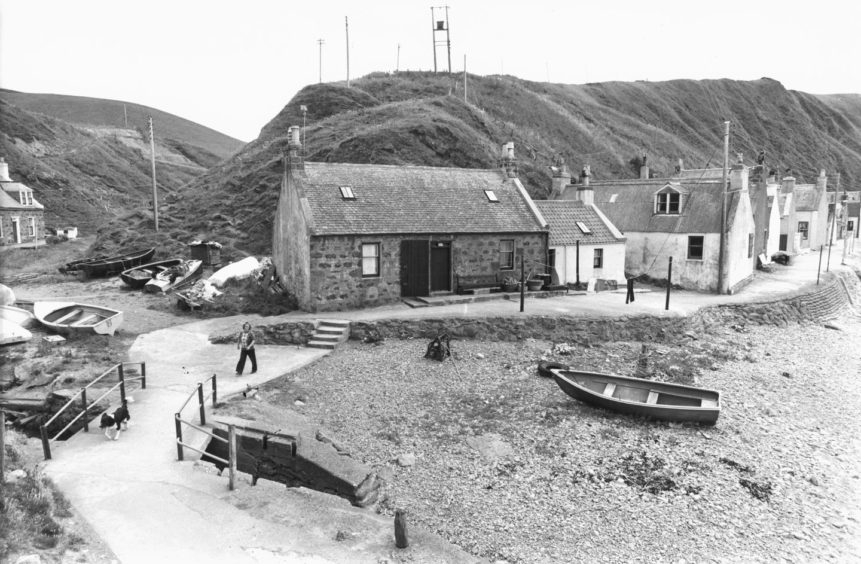

The thing that marks it out most is the traditional fishing cottages, most with gable end to the sea, as they perch precariously on a bankhead just feet from the Moray Firth.

It is one of the few villages in the UK with no road to the front door, and cars are parked at the bottom of the steep and narrow access road. A small L shaped pier bisects the village.

Residents and tourists have to take their shopping and sundries by wheelbarrow to their cottage.

Most of the descendants of the original fishing families have gone, and they were largely Watts, Wests, Websters and Wisemans, although I do recall Gatts, Reids and Johnston(e)s.

The fishing community was once entirely engaged in the sea and in herring fishing, and especially drift netting. The nets were set in mile-long curtains with floats and the fish swam in and were caught by the gills.

Great Storm

The 1953 Great Storm did not close the village, and it was several years before the residents left.

My grandmother left with her cousins to live in Harbour Street, Gardenstown, in 1960. I enjoyed many holidays in the 1950s, and my memory is crystal.

I can testify as an eye witness of a different time, of a unique fishing community and to a lively village filled with fisher families, loons and quines, retired fishermen recounting stories.

We see a place as we see it now, a group of small houses, but like St Kilda the reality of living there was different and vibrant.

In the 1950s few people had cars, with only two in Crovie as I recall.

Crovie was a remote village, with few visitors apart from the travelling people who came to sell their wares, or folks walking over from Gardenstown for their Sunday afternoon stroll. Do you still remember that?

Earliest recollection

My earliest recollection was my first visit to my grandparents from my home at “Cassie-end” Aberdeen that I can remember as a three year old.

I walked in to my grandparents’ cottage and the living room was pine panelled, and the bed was recessed into the wall.

There was a tiny kitchen and cooking was on a paraffin stove. There were steep stairs to the attic room which was filled with brown-reddish nets with light circular cork floats laid out in large heaps.

One of the nets coated with occasional scales was strung across the room and several women were mending holes in the nets in a quick and skilful manner.

The smell was of twine. A tilly lamp hang in the room corner and the window opened to a view over the “rotten shore” towards Gardenstown.

Seaside playground

Life was never dull as a child, with rock pools to explore and fishing with grandad for partins (edible brown crabs) with a pole and a large hook called a clipie that he pressed under rocks when the tide was out.

There were favourite spots for his creel which he would set from the shore at low tide and fling into sandy hollows between the rocks.

Up they came with lobsters and sometimes a fish that eye-balled you menacingly. A large prickly red and gold fish he called a sea sue or sanny sue, later to be revealed as a ballan wrasse.

My favourite name though was reserved for a sea scorpion which we frequently caught but could never eat and aptly named a ‘jocky gundy’.

A favourite walk was to the rotten shore, and in spring it would be rotten with the smell of washed-up seaweeds. My cousins John and Alan, large burly loons to my mind anyway, found this a favourite place for swimming and they eagerly rushed into the brine.

It was never an easy beach though, with large pebbles that continuously moved up and down the shore to give a noisy crashing effect that echoed off the steep brae behind.

My father, from Aberdeen, was welcomed, but viewed as a city boy. One day he told my grandparents that he would swim out and round the Black stanes, much to the alarm of the locals, as many of the fisherman could not swim.

But off he went and despite the cold and currents, tackled the swim with no problem.

My earliest memory of the boats was not a pleasant one. Grandad took us out in his robust wooden boat which apparently had belonged to his last fishing boat. There was no outboard, and everyone simply rowed.

So, we set out for our sail round the bay with sweets and picnic in hand. As a three-year-old, I felt very sick.

They often say that your clearest memories are the bad moments, and I never forgot my party piece.

Way of life

The retired fishermen met every day at the pier head regularly for a smoke and a catch up. I recall some had pipes and several smoked Capstan Extra Strength.

The men were all dressed the same with dark or grey ‘gansies’ as they called them in fancy pattern and cloth bonnet.

There was a broken-down building at the head of the pier, and they stood there and some on herring barrels and chatted.

Their main topic was always what the boats were up to, who had caught what, the number of crans (six fish boxes) each boat had caught.

I don’t know how they managed to get all this news as the fishermen could be away for weeks to places like Lowestoft, Great Yarmouth, South Shields and Shetland. Presumably someone had a phone (there was a lone telephone box nearby) or sent a telegram, or perhaps there was news from a fishing company.

They did not seem to mind me listening or my company, I was just a wee boy.

Another favourite was to watch my grandparents and the other Crovie folk head for church on Sunday morning dressed in their best clothes, along the rotten shore, the wee path below the primrose flooded braes round the “Sneuk”, through the New Ground at the east side of Gardenstown, up a wee hill to a place called the “bogue” and then up a steep hill to the Gamrie kirk.

I could see them go all the way to the Sneuk with binoculars, until they disappeared out of sight round the Sneuk.

When I was around seven years old, they would take me as well.

Grandfather Watt (by-name Bimmy!) was always first in the church so that he could get his favourite seat, the back row on the right corner. He was a shy man and did not want to be further up the kirk.

My favourite walk though was when grandfather would take us up on the braes behind the village to see the rabbits, and there were lots. The side of the brae was pocked with rabbit burrows and runs.

Grandad would take a long crook and pretend to pull a rabbit from a burrow, but of course they were much further down the hole.

An exciting feature was when we had to get all the folks to the pumps to draw some of these heavy wooden boats off the shingle beach.

The boats were stored in the open area in the middle of the village called the Green in which the burn ran through. The boats were often pulled up with the winch, but smaller boats were man hauled up over wooden rollers to the safety of the storage area at the top of the green.

There was great fun when several men and wee boys on each side of the boat helped push it up the green.

Changing times

So, where are the Crovie families now? Many moved to be near their fishing boats in Peterhead, Macduff or Fraserburgh, and some moved to new council houses at the top of the hill in Gardenstown, and later to new bungalows when incomes increased.

The village remains silent now with no fishermen, but the memory of the fishing community as it was remains strong. I recall the village as it was, a vibrant busy fishing village on the Moray Firth within feet of the sea.

And the Crovie people were a race apart, even to their neighbours in Gardenstown.

The families of St Kilda may have been lost, but the loss of the fishing families and community from Crovie is also a sad moment.

The collective of who we were, generations of fisher folk from a small remote village, has gone. The Crivie loons live on in the memory.

The narrative of the village is that it was immediately evacuated and deserted after the Great Flood of 1953, but I have to comment on that.

In subsequent years I frequently holidayed with my grandmother in Crovie and latterly in Gardenstown, and she never gave the impression that the seas and the Great Storm gave her any cause for concern.

The Crovie people were born to that lifestyle, and the windows on the gable ends of the houses had shutters fitted over winter.

The locals were used to winter storms and waves washing between the houses, which I witnessed with delight as a child.

The reason for leaving Crovie seems to be practical rather than as a result of the storm.

The fishing boats were getting larger, with fishing from Macduff and Fraserburgh, and some from Peterhead – so there was a movement of families to these towns.

My memory of the living conditions of my grandparents was that they were very basic; a paraffin stove for cooking, a paraffin tilly lamp for lighting, an outside toilet with only a bucket, and no electricity, shower or bath.

Few of the locals had cars and the village shop was modest, although with enticing sweets and Sang’s sublime lemonade. The elderly had quite a walk or trip to Gardenstown or Fraserburgh.

The way of life was hard and with few conveniences, so the lure to a location such as Gardenstown was attractive.

Was the sea a threat to the village as guide books claim? The few houses that were destroyed in the Great Storm were mainly at the east end of the village, and were parallel to the sea, and there was also damage to one near the Green, so my feeling is that these had less structural protection than the houses that were built gable on to the sea.

The proof is in the longevity of the village. It is almost 70 years since the Great Storm and the village is still intact, a memory of our fishing past.