After living in harmony with Mother Nature for thousands of years, the world of the aboriginal or First Nations Peoples of Canada changed with the mass arrival of European settlers in the 15th Century.

Their land was eventually taken, and their way of life disrupted. In fact, their lives would never be the same again.

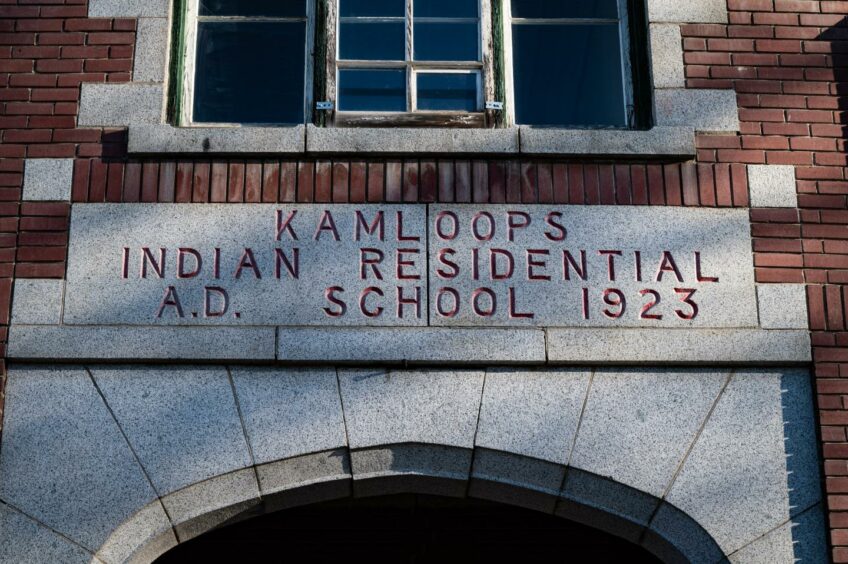

Arguably though, it was not the taking of their land that was the worst thing that happened to them. It was what happened after. By that I mean the forced residential school system. Or Indian residential schools as they were called at the time.

I’ve delved deep into it, and it makes for harrowing reading. Dates and figures I’ve taken from the trusted source of the Canadian Encyclopaedia.

Residential schools were Canadian government sponsored religious schools that were established to assimilate the indigenous or First Nations People into the European or new Canadian culture. As mentioned last week, we, the “white man” believed that our culture and our way of life was far superior. We felt therefore that we needed to civilise these “savages”. How ignorant and arrogant of us.

From the 1830s onwards, residential schools popped up all over Canada. The first one opened in the very state I’m in right now, Ontario. It was the Mohawk Institute in Brantford.

You can be forgiven for thinking that these forced schools were shut down long ago, maybe in the early 1900s. Sadly, astonishingly, these residential schools were still operating up until the late 1990s.

The Gordon Residential School in Saskatchewan was the last one to finally close its doors in 1996, bringing the curtain down on this shameful episode. That’s only 25 years ago.

So, what happened in these schools? And what was their purpose?

To “educate” and convert the indigenous peoples to European ideals. To eradicate their way of life basically. It has been called, and rightly so, cultural genocide.

First Nations children were first removed from their homes, taken away from their parents. Siblings were even split up, as the schools were often segregated by gender.

What was daily life like for children inside these schools? They were scorned, their culture ridiculed, forced to learn English or French, they were not allowed to speak their native tongue. Their hair was cut, and they were stripped of their traditional clothes. Children were also given new names. White Christian names.

Taken from a report in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada in 2015, we can learn of a typical day in one of these highly regimented schools.

Rise at 5.30am, praying at 6am, then bread making, washing and milking. At 7.15am children were inspected to make sure they were clean and “properly” dressed. After breakfast it was chores, then school work until midday. After lunch, more school, some recreation, then more chores such as carrying wood, coal and sweeping. After a spartan supper, some recreation was allowed, then prayers and off to bed at 8pm.

There were no classes at the weekend, but Sunday was of course for religious services. There were holidays, but this was often spent at the school. As a result of this policy, many children in the residentials schools system did not see their families for years. It wasn’t until the 1960s that the schools would, on a regular basis, send the children home for holidays.

The quality of education on the whole was said to be poor, and with classes taught in only English and French, the children found it extremely difficult to understand. The teaching staff were also said to be underqualified for the job.

On finally leaving the schools, many children were said to be disoriented and insecure. They felt they didn’t belong anywhere any more.

John Tootoosis, a former student at Delmas Residential School, said on leaving: “It is like being put between two walls in a room and left hanging in the middle… they washed away practically everything from our minds, all the things an Indian needed to help himself, to think the way a human person should in order to survive.”

Although the schools were established by government, they were in partnership with Christian churches. Never an organisation to miss an opportunity to “spread the word”, I’ve read that the Catholic church operated around 70% of these schools, yet the Anglican church and Presbyterian were also involved. They forced the children to learn all about Christianity while at the same time belittling their deeply held ancient spiritual beliefs. From what I can gather, there has been no formal apology from the Catholic church.

At least the Canadian government finally, in 2008, gave a historic apology to all former students of the residential schools system. It acknowledged and expressed deep regret for the harm done to the people’s culture, language and heritage, and the suffering individual students and their families experienced as a result.

Sadly, in these schools, abuse was rife. Excessive punishment for “getting things wrong” included soap being put in the children’s mouths, beatings and even being chained up. The stress this cause the children made many wet the bed. It has been reported by survivors that as a result of bed wetting, nuns would then rub urine in the child’s face as punishment.

Due to poorly kept records, we will never know the real number, but it’s estimated between 3,000 and 6,000 children died in these schools, due to abuse, malnutrition or disease such as smallpox, measles, typhoid, diphtheria, pneumonia and whooping cough.

Medical experts did call for measures to improve health and treatment, but these were not implemented by government due to costs and opposition by the church.

In 2015 it was officially stated that “…the residential schools regularly failed to provide the healthy living conditions, nutritious food, sufficient clothing and physical regime that would prevent students from getting sick in the first place, and would allow those who were infected a fighting chance at recovery.”

I find the entire subject of forced residentials schools deeply uncomfortable to learn and write about. Taking children from their parents and forcing them into another culture is horrific.

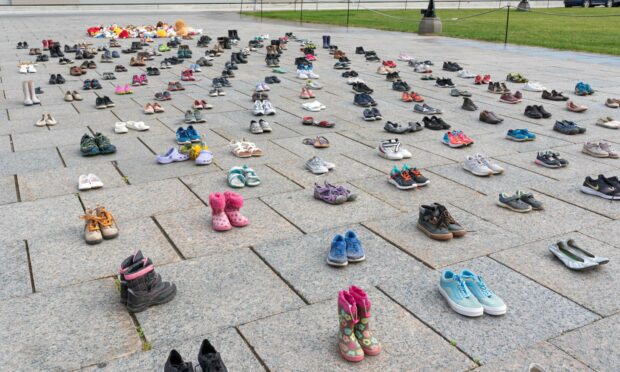

As you can imagine, the effects of these forced schools on countless children is still felt today. For example, only this year, the remains of 215 children were discovered at a former residential school in British Columbia. If that was not bad enough, weeks later in June 2021, 751 unmarked graves were discovered at another former residential school in Saskatchewan.

Investigations are on-going and it is “hoped” that the church will work with groups to investigate further. I wouldn’t hold my breath.

There is a lot more to come out I feel, and none of it good.

I did try to visit the local First Nations Peoples centre in Owen Sound, but it’s currently closed to all members of the public due to Covid restrictions.

I realise I have merely scratched the surface of this shocking history. There is so much more I can and want to write about. But time is of the essence and I have other interviews in Canada lined up. I plan to focus more on the plight of the First Nations People and hope to arrange a meeting with survivors on my next trip to Canada. Hopefully sometime next year.

Someone once told me that they didn’t fancy going to Canada as it was “boring”. Really? Wow, certainly not when it comes to history.

Moving on from the First Nations People, it was time to reconnect with Canada’s recent past. And by that, I mean the Second World War. No, not Charlie, not yet, but a remarkable woman. A woman who calls Canada home. A woman who as a teenager in Nazi-occupied Holland put herself in immense danger, in order to help keep her people’s spirit alive.