If we had to put a date on the birth of postmodernism, 1966 might be as good a guess as any.

That was the year Robert Venturi published his “gentle manifesto” Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, in which he took the modernists to task.

After Ludwig Mies van der Rohe advocated “less is more”, fellow designer Venturi insisted “less is a bore”.

(Then Dolly Parton said “more is more” and who are we to argue with the woman who gave us such classics as Jolene and I Will Always Love You?)

Venturi railed against “the great simplifiers” and rejected the assertion that form follows function.

Where minimalism was an evolution of modernism, maximalism is more closely associated with postmodernism.

Now, before you cast an appreciative eye across the bombsite that is your post-Christmas, pre spring-clean living room and declare “OK then, I’m a maximalist”, understand this, it’s not about having lots of stuff.

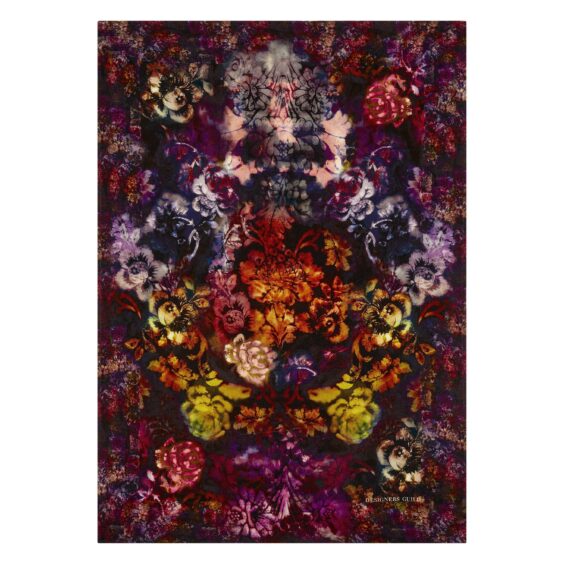

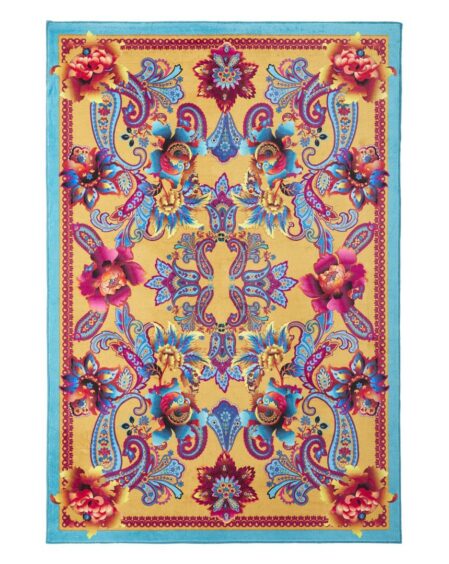

It is about an abundance of colour, pattern, texture, ornament, accessories, plants and artworks. It is playful, detailed and nothing has to match.

Where minimalism is about restraint, maximalism is about excess.

For the ultimate expression of maximalism, see fashion editor Diana Vreeland’s Manhattan apartment with its “Garden in Hell” lounge and then go lie down in a darkened room.

Surely no-one wants that. What we may want though, is comfort, ease, and treasured things around us, whether they are useful or not.

The minimalists are welcome to their clean lines and stripped-back aesthetic, because maximalism is not so much a statement as a story – a story about us, our lives and the place we call home.