To stand in the centre of the ancient yew trees at Ellon Castle Gardens is to feel as if you are standing in a cathedral.

This is a sentiment expressed by many, having glanced up at the gnarly canopy of branches – which have stood the test of time for at least 500 years.

To place your hand softly against the trunk is to touch history, to feel rooted by nature and all that it is able to weather.

Trees have long captivated people, perhaps because they stand as a measure of our own mortality.

The devastation caused by Storm Arwen has changed the conversation surrounding trees, with toppled giants a sobering sight.

Haddo House in Aberdenshire lost an estimated 100,000 trees, and as many as half a million on the wider estate. Recovering from the loss is expected to take a generation.

Trees are even on the royal agenda for 2022, and not just because The Duke of Rothesay visited Haddo earlier this month to survey the damage.

To celebrate the Platinum Jubilee of Her Majesty The Queen, the Queen’s Green Canopy initiative invited people across the nation to plant trees.

It is hoped the project will help the environment by planting trees sustainably. The first Jubilee tree, a Verdun oak, was planted in the grounds of Windsor Castle last year.

Verdun oaks were first planted in the UK as memorials following the First World War. The acorns used were collected at the battlefield of Verdun.

There is clearly a story to be told, and Your Life set about speaking to tree experts and enthusiasts – to find out if Storm Arwen has in fact made way for change.

Doug Howieson, head of operational delivery for Scottish Forestry

Scottish Forestry has already held meetings with Confor and Forestry and Land Scotland, to start planning the recovery of at least 4,000 hectares of woodland that have been affected by the storm.

The most intensive damage to Scotland’s woodlands runs down the east coast, across the Borders and East Lothian, stretching into Galloway. Another swathe of damage runs through Banffshire, Aberdeenshire, Kincardineshire, Angus and into Perthshire.

For Doug Howieson, far from being a disaster, Storm Arwen has delivered a priceless opportunity to reshape woodland for future generations.

“I’ve been involved for 34 years, one of the things I love about working with Scottish Forestry is that people believe in what we do,” he said.

“Who doesn’t love trees?”

Who indeed, which makes the images of flattened forests all the more sad.

But to truly understand that hope can grow again, we need to go back in time.

“There is a big storm probably every 10 to 15 years,” said Doug.

“But nature has a wonderful way of recovering.

“We need to remember that the Forestry Commission was first established in 1919.

“In the First World War, woodland cover dropped to 5% in Britain. We couldn’t access timber for the war effort.

“So we created a strategic timber reserve; Scotland in particular was exceptionally successful in doing so.

We’ve been at this forestry malarkey for over 100 years.

When we get a big storm, what that does is help forests bed in with nature better.

“It doesn’t always have to be a bad thing. With big blocks of the same species blown over, it can create more diversity.

“The difficult thing is of course in clearing up, but we think long term.

“It gives us the opportunity to make forests and woodlands more resilient for future generations.”

This can involve planting different species, and making way for trees of different ages to blend into the landscape.

“We can drive forward diversity of species and age distribution, which is by no means a bad thing,” said Doug.

“Of course it is devastating for people who have cherished woodland, nurtured it and walked in it.

“Bear with us, bear with nature and we will recover.”

With the damage not only documented but also talked about, Doug is hopeful that Storm Arwen has at least drawn attention to how forestry works.

“I think it’s good for people to understand the wide range of benefits which forestry provides, such as biodiversity,” said Doug.

“Trees store carbon and pull it out of the atmosphere.

“The trees that we plant now, we will never see mature.

“We are designing forests in a way which will inspire future generations.

“We’ve learned an awful lot over the last 100 years in terms of landscape design. So we are taking that knowledge that we have built over the decades.

What we’ve lost to Storm Arwen is a fifth of what we cut down every year. The difference is that we haven’t done it in a planned way.

“We have reacted to Mother Nature, as opposed to planning for it.”

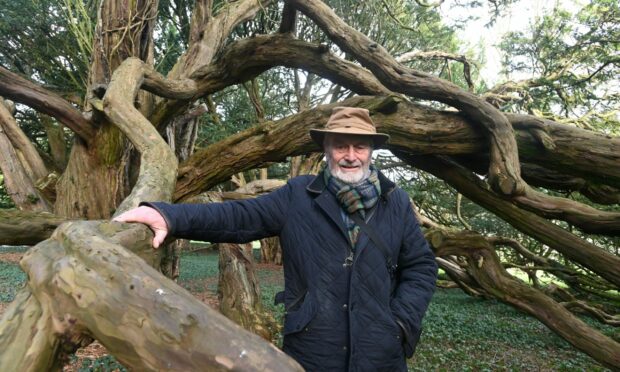

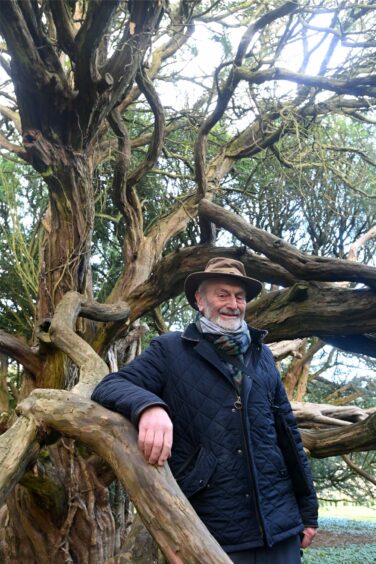

Alan Cameron, director of community engagement at Ellon Castle Gardens

Ellon Castle dates back to the 15th Century, and the gardens contain a unique collection of ancient English yews thought to be at least 500 years old.

A marvellous team enabled the gardens to be opened to the public in 2019, and the neglected site has been restored to resemble its former glory – after it was transferred back to the community of Ellon from private ownership.

A secret passage even exists from the old castle to the River Ythan, which is believed to have been used for smuggling brandy.

If only trees could talk, for the collection of 19 yew trees would clearly have quite the tale to tell.

For Alan Cameron, Storm Arwen has refocused the conversation surrounding trees and nature, after the gardens were fortunately left untouched.

“It’s difficult to age the yew trees as the normal way of counting the rings doesn’t apply here,” he said.

“The centre of the yew tree rots away, but measurements from 1858 and 1950 show that the ewe trees are at least 500 years old.

“The trees which fell at Haddo had very shallow roots, whereas yew trees have deep roots and of course they are in a walled garden which is relatively sheltered.

“We also have a row of around a dozen lime trees which are roughly 100 years old, and the most fantastic beech tree.

I think everyone who sees the trees are stunned. The gnarly branches come down and rest on the ground, where roots form and a new tree grows.

But what is it about the yew trees which inspire so many, and would have proven to be such a massive loss had they fallen during the storm?

For Alan, it is their longevity which sparks a connection.

“They have survived all this time, they are ancient and you can tell that just from how gnarly they are,” he said.

“The shape from an artistic point of view is just beautiful, the trees sell themselves.

“I think there is growing awareness due to climate change, that we must preserve and plant trees.

“We’re beginning to refocus on the fact that we must work with nature rather than against it.

“If you drive from Ellon to Peterhead, there are few trees. They were cut down because of people wanting to farm the land.

“We are beginning to rebalance. We have plans to plant trees in the deer park here and over the past year we have replaced 150 trees in what was formerly the yew tree hedge.

“They may only be around a metre high right now, but in around three or four years’ time there will be a really nice yew hedge.”

Chris Wardle, gardens and designed landscapes manager for Aberdeenshire and Angus at NTS

For Chris Wardle, who has worked for the National Trust for Scotland (NTS) for 22 years, Storm Arwen has made way for a much bigger conversation surrounding woodland management.

“I think it has shown the disconnection we have, because woodlands are in fact like farms,” he said.

“Trees are just like wheat, they are a crop and are part of a big reserve.

“Plantations get a bad name, but we need to wind the clock back to the First World War.

“It was a close run, people don’t realise that we almost lost the war because of timber.

“To make weapons, you have to get coal. The coal pit props were made out of wood, and we did not have a strategic reserve of timber.

“The Forestry Commission was set up in 1919, so if our backs were ever against the wall we would have sufficient timber.

“One of my mind blowing facts is that Vanillin, which is used to add that vanilla flavour, comes from wood. Without trees, we wouldn’t have vanilla ice cream.”

Chris estimates that 60-70% of plantation forestry has been lost at Drum, with around 60% at Craigievar.

Monocultures, meaning the cultivation of a single crop in a given area, can be susceptible to disease and are not resilient to big climate events.

But there is still a need for them, not least in sucking up CO2.

“Plantation forestry can convert CO2 very efficiently and quickly; the downside is that there is no resilience,” said Chris.

“We’ve already started the conversation for restructuring our woodlands, and the way people interact with the countryside.

“Our thought process is that we need to create diversity, a space for both wildlife and people.

At Drum Castle, it is an ancient woodland pasture. There are only 20 of them in the UK, and we have one of them.

“The part that blew down was round the outside, meaning we have the opportunity to replant for 300 years down the line.

“We can put back the woodland pasture system with cows grazing under huge trees.

“It has started the conversation of how we managed woodland, and how we’ll manage it in the future.

“The countryside is going to change, and as humans we need to change what we do in order to fit that.

Loss of woodland is always seen as devastating. But we are not sentimental, we are pragmatic.

“It has happened and we can’t change that. We need to move on and put something in place for the future.

“This is for our children’s children. It’s all about legacy.”

Sentimentality may not be the order of the day, but Chris is not immune to the feelings that trees can provoke.

“Trees are emotive and I think we are very lucky in Scotland,” he said.

“People know who they are. They know their identity, which is very strong in Scottish people.

“It is the mountains, the bogs, the wind, the water and the forests.”

Struan Dalgleish, arboriculture consultant

Planting trees is all well and good, but if you don’t know what you’re doing it can prove problematic in the future.

Struan Dalgleish studied trees all over the world before returning to Aberdeen, having studied forestry at Aberdeen University before becoming an arboriculturist.

“It’s a mouthful, but it comes down to all the good reasons there are to have trees in the landscape,” he said.

“There’s scenic purposes, oxygen production and carbon storage, water management, air purification and noise abatement.

“I think there is a growing awareness surrounding the importance of trees; my kids are far more clued up then I was at that age.”

Struan’s work mainly involves dealing with conflict, caused by people and trees living side by side.

He has spent the past month inspecting trees which have been damaged and compromised by the storm.

“I think you can become very familiar with trees because they are so long lived,” said Struan.

“They become almost like old friends, especially if they are part of childhood memories.

“They can have so much character and mature trees in particular can be like big wildlife hotels.

“Planting trees is a great thing, but it’s important to plant the right tree in the right place.

“I often see the conflicts caused by trees which have outgrown their location.

“Native trees do well, but evergreens have the most issues.

“You need to get the right size of tree for the space you have, and of course get it managed properly.

“I love the Caledonian pine forests up at Deeside in places like Marr Lodge and Braemar.

“These are old pines which have been undisturbed and it’s been like that since the last ice age.”