The lifeblood of the valley for many centuries, the beautiful River Spey is Scotland’s second largest river after the Tay, meandering through 109 miles of countryside with over 520 miles of tributaries and feeding 52 world-class distilleries.

The Spey, which covers 1,864 sq miles, also supplies water to eight hydro-electric power stations, including an aluminium smelter, as well as hosting a thriving leisure scene.

On February 11, the salmon fishing season officially opened on the Spey, which will run until the last day of September this year.

Welcoming back anglers to its shores and preparing for another busy tourist season, the Spey Fishery Board (SFB) has a broad remit when it comes to management and care of the vital waterway, alongside the 20 miles of Moray coastline it is also responsible for.

Roger Knight, Spey Fishery Board director

The Spey is home to some of the most varied wildlife and biodiversity in the country. With so many interests dependent upon its crucial water supply, the Spey is under immense pressure and – as Roger Knight knows all too well – fast running out of options to maintain its viability.

The biggest area in which we can make a difference is to reduce the amount of water being used to generate hydro electricity

While Roger deals with statutory agencies, the Scottish Government and the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), his team of managers and bailiffs, along with other agency partners, are responsible for slowing – and reversing – the threats from invasive species, climate change and water abstraction.

An SFB-commissioned study showed that Spey water levels are reduced by up to 61% at Kingussie, and the organisation has called on the Scottish Government and SEPA to take action.

Roger says: “The biggest area in which we can make a difference is to reduce the amount of water being used to generate hydro electricity.

“The Spey is one of the most abstracted rivers in Scotland. We have water taken out of it to generate hydro electricity, we have drinking water supplies and water for agricultural purposes.”

Currently, distilleries “borrow” the Spey water for cooling and return it to the river.

However, of all the water taken out, up to 91% of it is diverted out of the top of the catchment area to generate hydro electricity, water which is permanently lost to the river.

“What this has done over eight decades is denude the Spey of its ground water resupplies,” says Roger. “It’s not as though it can be topped up by a few days of rain. It has made the Spey far less resilient to the impact of climate change.

It’s not something one organisation on its own can tackle – it needs a shared partnership approach

“Whilst hydro electricity is renewable, it’s not green because it’s having a devastating impact on the ecology and biodiversity of the rivers it’s taking that water from.

“There is now a much wider portfolio of energy generation. We’ve got onshore and offshore wind, solar and tidal power – there are more modern methods of generating electricity.”

Shared partnership approach

Roger believes a broader, more “holistic” approach, is needed in the way the Spey catchment area is managed.

He adds: “The projects that we’re looking towards now are going to have landscape scale change to help make the river sustainable and more resilient to climate change, and try to avert the biodiversity crisis in the process.

“It’s not something one organisation on its own can tackle – it needs a shared partnership approach.”

Duncan Ferguson, operations manager

A former head bailiff, Duncan Ferguson oversees the day-to-day running of the Spey but also facilitates inter-agency working to help establish conservation projects.

Duncan was the man behind the award-winning Allt Lorgy project near Carrbridge in 2012 – the first of its kind in the UK, taking the River Restoration Centre UK River Prize in 2020 for the radical regeneration and transformation of an approximate 850-metre stretch of water.

Allt Lorgy was the earliest and most advanced example of “Stage Zero” restoration in the UK, and set a template for other conservation projects to follow.

Involving the planting of trees on the edges of the river and the placement of structures (fallen trees) within the river to provide shelter for fish, the previously artificially straightened river has now returned to its original winding path, aiding flood management.

Basically, everything that man did, we need to undo

“Fish also live in trees,” Duncan assures me, pointing to the structures in the water. “Once upon a time these would have been cleared out, which impacted fish stocks. But these wood structures provide refuge areas and cooler water, which fish like salmon need.

“Salmon are the best indicator of the water’s health and the habitat,” he adds. “If the salmon are happy then it means nature is working as it should.

“Basically, everything that man did, we need to undo.”

Duncan points to several trees along the banks, identifying non-natives to be removed, and the fencing that reduces browsing pressure from livestock and deer as the trees become established – all of which must have local provenance.

“The fencing is capercaillie-proof, too,” he says showing the slats in the high deer fences to help them avoid flying into it. Capercaillie, which breed in wooded areas, are a good indicator of forest health.

Natural flood management

Previous images show a somewhat stripped-back landscape and it’s clear why the Allt Lorgy was award-winning. Previously lacking in fish and other wildlife, it has changed to a dynamic, winding, re-naturalised burn, rich in new habitats and species.

“It was artificially straightened before – canalised – for agricultural gain,” says Duncan. “This speeds up the water flow but the river ceases to function properly.

Effects of climate change

“For natural flood management you want it slow, to protect young fish. But the knock-on benefit is downstream communities because there’s natural flood management as well.”

And on the Spey, climate change is felt directly.

It’s really important that you know what you’ve got and what you’re trying to achieve

“Nowadays when you get a spate it’s a sharp peak, which causes more damage,” says Duncan. “It washes fish out and knocks trees down, like having the two storms back to back. We’re trying to slow these events down.”

Currently Duncan is overseeing similar, continued work on the River Calder at Newtonmore, this time on a larger scale along about three miles of the river.

And future projects will likely involve closer examination of carbon capture and storage.

“It’s really important that you know what you’ve got and what you’re trying to achieve,” says Duncan.

“Every little bit that we do adds up to a bigger picture.”

Penny Lawson, project officer

Penny is project officer at the Spey Catchment Initiative, a partnership of agencies invested in restoration and sustainability of the Spey.

Her job involves finding projects and examining proposals for restoration and conservation work, habitat improvement, sourcing the funding for them, working with landlords and “connecting communities with the river”.

That is a huge factor in our successes – personal contacts

She says: “The fundraising I’m doing is for specific projects, like the Allt Lorgy.

“A lot of our rivers have lost woodlands along the side so we’re keen to plant trees for shading so that the water temperatures are controlled.”

Projects to re-wild and for habitat improvement can take anything from six months to several years, says Penny, emphasising the role of people in getting projects off the ground and “keeping plates spinning”.

Building capacity

“Having support from Duncan and the fishery board is critical because they know the river so well,” she says.

“Duncan has been on the river for 30 years so he knows all the catchment, the physical characteristics of it, the people that are involved, the ghillies, the bailiffs, all those crucial people.

“That is a huge factor in our successes – personal contacts.”

We need to get bigger and better at what we do

In addition to SFB, steering group members include SEPA, Nature Scot, Cairngorms National Park Authority, National Farmers Union Scotland and Woodland Trust, among others.

Together, they offer a direct line of contact to get the ball rolling fast and avoid losing momentum on urgent projects. And every little helps.

Penny says: “There is money being put into this with commitments from COP26, and there is government support, but we need to build capacity to do more big-scale projects.”

“We need to get bigger and better at what we do. It’s a huge catchment.”

So what has been the most successful project to date?

“I don’t have to think too hard about that one,” she says. “It was doing the restoration on the River Calder 2019-21. That was far and away the biggest project that we’ve done.”

“It was truly on a landscape scale and will lead to really significant, long-term benefits for that catchment,” Penny adds. “It really feels like it’s going to make a big, genuine difference.”

James Symonds, project officer

The success stories are heartening, and in the face of overwhelming odds, boots on the ground are making an impact.

James Symonds, project officer at the Scottish Invasive Species Initiative (SISI), focuses on plant and animal species covering the Spey and the Findhorn, Nairn and Lossie river catchments.

In the lower Spey there are acres and acres of Japanese knotweed. Nothing else can grow

He is in no doubt that the work is worth it, with volunteers, ecologists, bailiffs, ghillies, locals and anglers all doing their bit to support efforts to protect and restore the Spey.

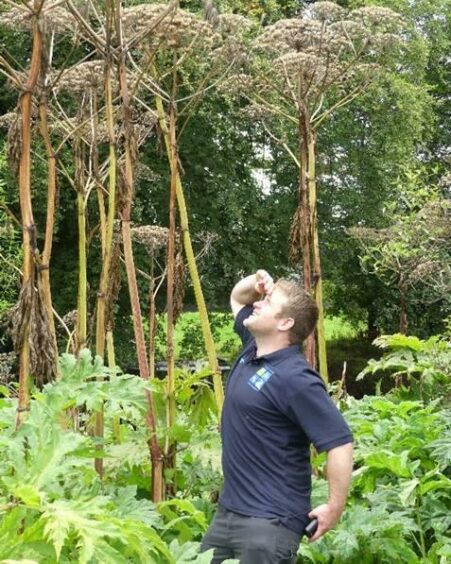

James says: “The SISI project had a list of target species to remove which was giant hogweed, Japanese knotweed, Himalayan balsam, American skunk cabbage and the American mink.

“I work with landowners and local communities to control these species. I try to recruit volunteers locally to upskill them for tickets (licences), using herbicides for giant hogweed and other species,” he adds.

“In the lower Spey there are acres and acres of Japanese knotweed. Nothing else can grow,” he says. “It completely overtakes huge areas. We treat these plants that are blocking out all other native plants, and it gives them a chance to recolonise and re-establish themselves.

“It’s an ongoing battle, though. Giant hogweed seeds remain viable for 10 years or more, so it really is a long-term commitment.”

There’s great local participation and volunteer hours, and the successes we’ve seen have been huge

But when funding stops, the work stops, says James. And one year where plants go to seed can mean a lot of good work undone.

“We’re really looking at some kind of continuation,” he adds. “Invasive non-native species are one of the main five contributors to loss of biodiversity, so it needs to be done.

“There’s a big push for tree planting as we’re moving to a low carbon economy now. But there’s no point in planting trees if there’s a big field of giant hogweed standing there.”

Tackling invasive species

Although it can take many years to remove invasive species, communities are keen to get involved. With his band of volunteers and experts, James works to clear land first to ensure the best chance of native plant survival, getting his hands dirty as he teaches the teams.

“I lead by example, as do my colleagues,” he laughs. “There’s great local participation and volunteer hours, and the successes we’ve seen have been huge.

“I do have volunteers who have their herbicide ticket and are keen to get to work, and who will bring friends along.

“We can achieve a lot just through volunteers,” he says. “It’s fantastic.”

Volunteers are also needed for the American mink project, says James.

Volunteers play crucial role

“I’m always on the lookout for volunteers for our wildlife monitoring raft for up and down the Spey,” he says. “They just check a floating clay pad once every two to three weeks and tell me what footprints they see.”

James also helps volunteers access training in herbicide distribution, along with advice and training for landlords to help manage their lands in a sustainable way, saying the feedback has been “overwhelmingly positive”.

It’s very positive for the future of our rivers

And he has nothing but praise for the work of the SFB and Scotland’s fishery boards.

“The days of the 60s and 70s when it was only about salmon numbers, they’re well and truly over. All of the fishery trusts are now moving towards a broader scope of work involving invasive species and habitat restoration.

“It’s very positive for the future of our rivers.”