A mass of gannets on open wings spiralled in the air above me, accompanied by a clamouring cacophony drawn from the heart of nature – a wild calling of the ocean, so entrancing that I yearned to become more deeply immersed within its warm embrace.

The towering cliffs of the Isle of Noss in east Shetland brought a shadow over the sea and there were seabirds everywhere: gannets, guillemots, razorbills and fulmars, all with an air of urgency as they shuttled back and forth to their nesting ledges where rapidly growing down-fluffed youngsters sat on impossibly narrow rock ledges.

These magnificent cliffs cradled the dawn of new life, yet death was all around too, and near our boat, a bonxie swam around the body of a young gannet that had fallen into the sea from its precarious ledge, pecking and stabbing upon the remains with its formidable hook-tipped beak.

Life can be so cruel and short. If this youngster had not had the misfortune to fall, probably as the result of a squabble with another gannet, it could have looked forward to a long life, perhaps of up to 40 years.

New book

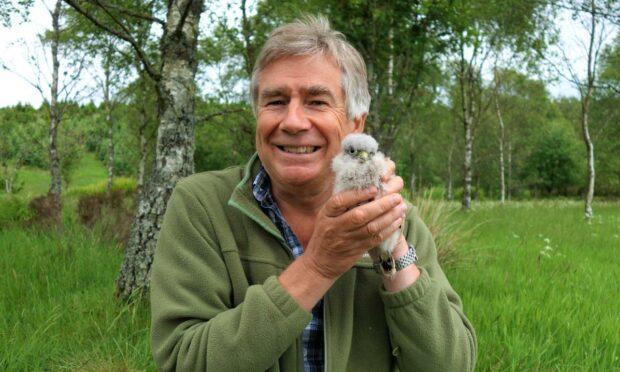

This was a scene indelibly printed upon my mind from July 2021, when I was nearing the end of a five-month journey researching my new book – A Scottish Wildlife Odyssey – which has now been published.

It was a wonderful journey from south to north, which began on the frost-laded merse of Dumfriesshire in search of barnacle geese and ended in the northern isles.

There were many highlights as I slowly zig-zagged my way up through Scotland, including a fascinating population of water voles in the east end of Glasgow which had forsaken water and had adopted an underground living existence.

Nature’s ability to adapt and evolve never ceases to amaze.

Wonderful wildwoods

My wanderings across the northern half of Scotland were especially compelling and included the towering seabird cliffs at Fowlsheugh near Stonehaven, the Sands of Forvie National Nature Reserve north of Aberdeen, as well as the high tops of the Cairngorms.

In the wildwoods of Strathspey, one memorable encounter was discovering a family of scarce goldeneye ducks in a remote forest lochan.

These lochs and tarns that lie scattered in the ancient forests of Strathspey hold an abundance of invertebrate life, which makes them truly captivating places.

I observed: “On watching the iridescent flashes of the damsel and dragonflies whizzing across the water of these lochans, I reflected that it was the insects that made the wildwoods of Strathspey so special.

“The crested tits, capercaillies and crossbills get all the plaudits, but the insects are the driving force of much of the life here, and their colour and variety are a joy to behold.

“Whether it be the miracle of wood ants ‘milking’ aphids for honeydew, the spectacular hunting dashes of dragonflies and damselflies or the death rush of a prowling green tiger beetle, the true drama of the wildwood lies in its spectacular invertebrates.”

Highlands and Islands

My journey then took me to the fossil-rich shoreline of the Moray Firth at Eathie in the Black Isle and then on to the Outer Isles and the wondrous flower-spangled machair, which abounded with breeding waders such as dunlins, redshanks and lapwings.

Journey’s end was Shetland, which brought both highs and lows.

I adore Shetland for its wildlife and inspiring landscape, but as our small boat bobbed in the water by the Isle of Noss, a tragedy was unfolding before my eyes.

By the fringes of one large sea cave, a small nesting cluster of kittiwakes had taken such a toll from the bonxies and great-black backed gulls that now only a handful of nests still held young.

Bonxies, kittiwakes and other seabirds have coexisted in balanced harmony since the dawn of time. But today, more insidious forces are at work, driving a decline in kittiwakes and many other seabirds due a dearth of sandeels to feed upon.

Breeding numbers of kittiwakes have catastrophically plummeted over the last two decades. The underlying problem is related to our warming seas, which has led to planktonic ecosystem shifts resulting in a decline in the abundance and size of sandeels.

Kittiwakes are especially vulnerable to food shortages as they can only take prey such as sandeels, sprats and juvenile herring when they occur at or near the surface of the sea, unlike deeper-diving species such as gannets, guillemots and razorbills which have access to a greater variety of prey in the water column.

It is a vicious circle.

As kittiwake nesting colonies get smaller due to lack of food, they become even more liable to predation by bonxies and gulls because there are fewer adults about to defend their nests as a large protective group.

Popular puffins

Later that week, I visited Sumburgh Head on the southernmost top of Shetland where puffins abounded.

They were a joy to watch, but almost as addictive as the puffins was observing the reaction of tourists revelling in being in proximity to them.

In my book, I remarked: “The obvious pleasure of the visitors was evident from the smiling faces of both children and adults alike, which underlined more than ever our close bond and connection with nature.

“We are as one, living in the same world and dependent upon a healthy environment for our future wellbeing.

“Sadly, like the kittiwake, puffin numbers around Shetland are in freefall, a testimony to the failure of humanity to act and bring about urgent change.”

A Scottish Wildlife Odyssey is published by Tippermuir Books and can be purchased at www.tippermuirbooks.co.uk, as well as other online sellers and good bookshops. Keith’s previous book – If Rivers Could Sing – was shortlisted at the Scotland’s National Book Awards 2021.