Jay Rayner, that famously forthright food critic, has only been on the phone a minute. And already he’s apologising.

I’d asked him to name a fond culinary memory from the north of Scotland. Typically, Jay’s mind leaps to the worst.

“I almost feel embarrassed,” he says. “You asked this question and I mentally rolled through my rolodex only to think back to the hideous experience I had in Inverness.”

Ah, Inverness. This was where in 2017 Jay suffered a chilly reception at an upmarket restaurant. It was a visit leavened only slightly by a far-better experience at another restaurant, The Kitchen.

And that is all I will say. I won’t give you the full story, partly because Jay has already detailed the experience in one of his many reviews for the Observer newspaper.

But mainly because his version beats anything I could muster. Suffice to say, the review includes the phrase: “I’ve had more fun at the chiropodist, getting my corns removed.”

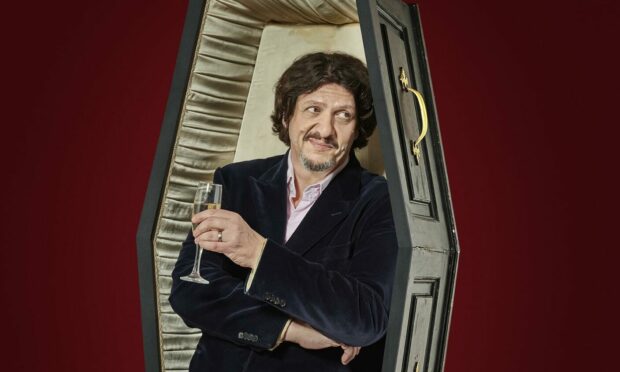

Jay Rayner on stage in Braemar

The Inverness story may well get an airing at St Margaret’s Braemar this Saturday, when Jay brings his one-man stage show to Royal Deeside during one of only two Scottish dates for the UK tour (Rayner is in Perth on 22 May).

If it does, it’s because the worst experiences make for the best stories, especially those that are recounted by Jay Rayner.

But though he’s aware that some people read his Observer reviews just for the take-downs (his 2017 evisceration of the insanely-expensive Le Cinq described the Parisian restaurant as a “broad space of high ceilings and coving, with thick carpets to muffle the screams”), Jay at heart is a champion of food, and those who serve it up.

Which is why he asks me to point out that despite the horrendous experience in Inverness (actually Nairn, but close enough), the review the Observer eventually published was ultimately a very positive one of The Kitchen.

It is also why he has written books on a broad range of issues that affect the food industry, issues such as food insecurity (on which more later) and the pressures of working in hospitality.

Meanwhile, the book he is touring in Braemar – My Last Supper – packs all of his love for food into one imagined final meal, with dishes inspired by his years at the frontline of restaurant reviewing.

The other side of the story

But there is a strong streak of contrarianism in Jay: here is a man who has never met perceived wisdom he hasn’t knowingly undercut.

His Inverness story, for example, slips seamlessly into a dig at Scottish restaurants that stick too close to the typical menu of salmon and venison.

(“There should be absolutely no reason why the good people of Inverness should not want to get their hands on something a little more… evolved.”)

The trend for tasting menus also gets a blast.

“When someone says: ‘And today, we are going to serve you nine courses, a little bit of me dies inside.”

Later, he even has a go at the almost literal sacred cow of Scotland’s world-class livestock, saying that it’s not enough just to have the best meat and fish, you need to be able to cook it well. Anything less is just “salesmanship”, he counters.

What does Jay Rayner think of rowies?

All of which brings us to butteries.

Jay admits to having done a bit of research on the north-east staple before speaking to the P&J. He’s not sure if he’s eaten one, but he knows the type.

After all, Aberdeenshire is not the only region in the world to pack its fishermen off to sea with calorie-laden baked goods, and Jay namechecks the Sicilian Pani ca meusa and the Cornish pasty.

It doesn’t take him long, however, to go down a previously underexplored avenue of butteries debate – how they re-enforce dangerous ideas of self-expression.

Of course, he doesn’t quite put it like that. He couches it as an attack on the Product of Geographical Indications (PGI), the scheme that means Parma ham can only be made in Parma and Champagne only in Champagne. But in essence, what he is suggesting is that butteries breed nationalism.

“The slightly troubling thing about food is it’s a very easy way to express identity,” Jay says. “I get a little bit uncomfortable with some of that.”

The benefits of the modern food industry

As is often the case, though, there is a serious point to Jay’s non-conformity. We discuss the use of palm oil in modern buttery baking in place of lard. I expect him to stick the boot in, but by now I should have known better.

Jay makes it clear he has little love for the palm oil industry. But he maintains that knee-jerk criticism of the food industry does no one any favours.

As he points out, modern farming methods for animals may not be great for livestock but they’ve been pretty good for humans. We no longer die of protein malnutrition in quite so many numbers.

Also, who’s to say butteries tasted better back when they were made with pig fat?

“There is this fantasy in certain food circles that 200 years ago we all ate beautifully,” Jay says. “No, not really. Most of us were living on millet.”

Food insecurity at a new peak

Worryingly, Jay senses something of a return to dark days of food shortages in today’s supply chain crisis.

“The UK is on the verge of food security concerns not seen since the Second World War,” he says, pointing to Covid-19, Brexit and the war in Ukraine. “In terms of food security, we don’t produce enough of our food.”

It is a serious point, and one underpinned up by Jay’s journalistic credentials. Almost a decade ago, he wrote a book called Greedy Man in a Hungry World that examined the thin cord that keeps the UK tethered to its food supply. Throughout his career, he has maintained a concerned eye on Britain’s food network.

So I wait for him to say more. A damning indictment of government policy on child nutrition. A telling anecdote on farm subsidies. But no. Not this time.

“Can I go back to the butteries for a moment?” he asks.

And we’re off again.

How to book tickets to see Jay Rayner in Braemar

Jay Rayner will bring his show My Last Supper to St Margaret’s Braemar on Saturday May 7.

Tickets are still available and can be purchased here.

Conversation