Every day.

It was my ritual, the thing I held on to.

Every morning during the strictest lockdown, I filled up a small flask, strapped the dog on the lead and headed out to meet my pal, Flora MacDonald.

She was no more than a statue by Inverness Castle – but since I was not allowed to meet my actual friends, or venture further, or go out more than once a day, she’d have to do.

This year sees the 300th anniversary since the real Flora MacDonald’s birth in 1722 – the exact date is uncertain.

Flora occupies a cherished place in the Scottish psyche – let’s face it, we’re all romantics at heart, aren’t we?

She was the young woman who risked everything to smuggle the fugitive Bonnie Prince Charlie from Benbecula to Skye in the aftermath of the Jacobite defeat at the Battle of Culloden, famously dressing him up as her Irish maid “Betty Burke”.

Government forces were looking for the prince everywhere. In addition, there was now a price of £30,000 on the prince’s head – an eye-watering sum, especially in those days.

The stakes were high – known Jacobites were often executed. Some were shot outside the Old High Kirk in Inverness; others taken to England for trial. And in this climate of fear, a young woman dared to defy the authorities to help a fellow man in desperate need.

A daring journey

Since her stepfather had pledged support for the government side rather than the Jacobites, Flora was permitted to travel with a small entourage. When a companion of Charles Edward Stuart pleaded with her for help, she relented.

On June 27 1746, the group set sail, travelling from Benbecula to the northern end of the Vaternish peninsula on the Isle of Skye, where they arrived on June 29. The eponymous Skye Boat Song (published in 1884) was inspired by this journey – a tune surely familiar to fans of the TV series Outlander, which features a haunting version as its theme tune.

Who could forget it?

Speed bonny boat like a bird on a wing,

Onward the sailors cry.

Carry the lad that’s born to be King,

Over the sea to Skye.

Strong-willed

Flora was a remarkable young woman, there is no doubt about that. Not only did she agree to take considerable personal risks for the prince, she also held her own against men used to being obeyed.

It is said that she absolutely refused to help Charles Edward Stuart if he was armed, much to his irritation. In addition, she insisted that the prince left his Irish friend Felix O’Neil behind.

Both men protested vehemently, but Flora was of the view that O’Neil’s “foreign air” would give them away – and in any case, she was only allowed one male guardian to accompany her, a local Jacobite in the role of her “manservant”.

Even after that fateful journey, Flora MacDonald’s life was full of dramatic twists and turns: she was arrested and held at Dunstaffnage Castle for questioning before being taken to the Tower of London for a time.

On her release, she married and later emigrated to North Carolina where the family arrived just as the American Revolution was brewing. Her husband joined a regiment of Highland Emigrants and fought for the British but was captured.

Flora was forced into hiding while the family plantation was lost and eventually chose to flee back to Skye where she and her husband were reunited and lived out their days at Kingsburgh.

New Jacobite book

Amid the current redevelopment of Inverness Castle into a tourist destination, Flora’s statue is inaccessible to the public for the moment. No more daily selfies with Flora, I’m afraid, and it saddens me because I have news for her. I have written a book about the Jacobites, and you have your own chapter in it, I want to tell her.

As I waited for the cogs of the publishing machine to turn, I imagined a publication day snapshot: Flora and her stone dog, me and my mutt – and the book. No matter.

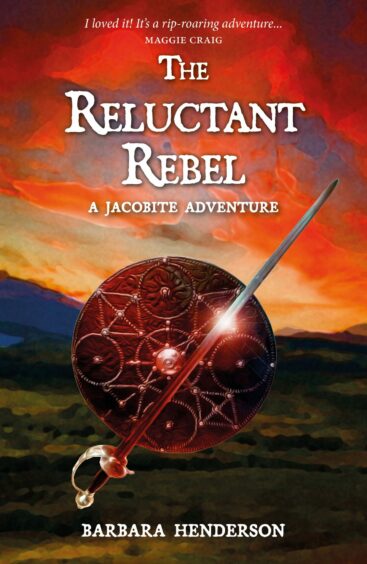

I launched The Reluctant Rebel with a school audience at Culloden Battlefield instead. After all, it’s an adventure story for young people about the aftermath of the Battle of Culloden and the deadly game of hide-and-seek involving the prince, Flora and many others.

Flora MacDonald may have captured the Victorian imagination as a romantic heroine, just like Grace Darling of Northumberland did – a pretty young woman bravely defying deadly danger. But there were many more remarkable stories, and Flora certainly did not have a monopoly on courage.

Historical records abound with tales of Jacobites who risked everything, over and over again, for their prince.

As a children’s author, I needed to find children at the heart of Charles Edward Stuart’s flight. For me, that was where the story was – a prince on the run for more than five months, often literally crawling through heather.

Try as I did, I could not find children who accompanied the prince for any length of time at all.

Finding our heroes

But wait, what if I found a house the prince passed through on several occasions? A loyal family who harboured him again and again. And bingo – I found Borrodale in Moidart. The Prince came here before the Raising of the Standard at Glenfinnan which began the rebellion on August 19 1745, and he also fled to Borrodale after Culloden.

When the net began to close around the islands where he was hiding, the prince returned to seek help at Borrodale once more and was aided by the family for the weeks in the wilderness which followed.

Ships from France finally succeeded in making contact with the fugitive, who returned to Borrodale to sail to safety.

Now finding child protagonists became easy. In my imagination, Archie is the stable boy at Borrodale, disillusioned by the death of his father early in the campaign. Meg is his cousin and a maid at Borrodale House. Both are astonished when the fugitive Charles Edward Stuart appears on their doorstep, and his fate suddenly rests in their hands.

Angus MacDonald, Master of Borrodale, had three sons. One died at Culloden, but the two remaining sons, Ranald and John, became instrumental in the prince’s escape – and both feature prominently in my book.

Then there was the little-known Roderick Mackenzie whose grave and memorial can be found in Glenmoriston.

Bearing a striking resemblance to the prince, Roderick acted as a decoy. When government militia discovered and shot him, he selflessly exclaimed “you’ve killed your Prince”.

It is likely that this may have saved the life of the real royal fugitive who was hiding nearby at the time.

A land steeped in history

Before I began writing The Reluctant Rebel, I travelled to the west coast and had a cup of tea with a local farmer. He showed me a jam jar filled with musket balls he had found in the stream behind his house.

He even found the tool to shape the heated lead into musket ammunition.

I was astonished: it happened right here, by the stream I could hear through the open door.

I don’t know whether these traces were left by Jacobites or by government forces, but I am certain of this: history is beneath our feet. This very soil is steeped in stories.

The north of Scotland would never be the same. Retribution was swift and deadly: Jacobite sympathisers were arrested and often executed. The clan system, so crucial to the organisation of the rebellion, was systematically dismantled.

All along the coast, the dwellings of Jacobite clansmen were burned to the ground, Borrodale among them. The widespread use of Gaelic was stifled, the wearing of tartan banned and bagpipes, the sound of the rebellion from its first day at Glenfinnan, was all but silenced for almost a century.

The prince himself is said to have exclaimed “Oh God, poor Scotland!” when waking from a nightmare while resting on Raasay.

There is little doubt that he was right to pity the country he plunged into such chaos, whether he did so intentionally or not.

Research journey

From the start, my fascination with the flight of the Prince was strong. I became a little obsessed, truth be told. My research trips took me to Lochaber, the hotbed of Jacobite support, from Glenfinnan to Skye, but also to Culloden and to Ruthven Barracks where the Jacobite army was disbanded for good.

I took my time, wandering around Borrodale and the shores of Loch nan Uamh where French and government ships fought the last sea battle in British waters, and where the prince departed to safety, never to return.

Much of this landscape remains unaltered. The waves of the loch, the shapes of the hills, the caves and the crags, the rustle of the heather in the breeze. We can walk in the footsteps of those who went before.

And as we remember their stories, they merge with ours.

Jacobite destinations to visit this summer

Click on the map for more information

Glenfinnan, National Trust for Scotland

Glenfinnan boasts more than just a visitor centre – there is a picturesque monument by the loch and impressive mountainous landscape all around. The viaduct of the Harry Potter films runs above, crossed by the steam train to Mallaig at regular intervals.

www.nts.org.uk/visit/places/glenfinnan-monument

Culloden Battlefield, National Trust for Scotland

The fantastic visitor centre tells the story of the final land battle on British soil, fought on April 16 1746 and the Jacobites’ decisive defeat.

www.nts.org.uk/visit/places/culloden

Loch nan Uamh

There is a memorial cairn by the side of the loch which commemorates Prince Charles Edward Stuart’s departure from here to France, five months after the Battle of Culloden.

www.britainexpress.com/scotland/Highlands/countryside/princes-cairn.htm

Ruthven Barracks

It was here that the Jacobite army was disbanded. Each man was to see to his own safety as best as he could. There was great dismay at this news. Now, Ruthven is an atmospheric ruin with a wonderful location, backed by the Cairngorms.

www.historicenvironment.scot/visit-a-place/places/ruthven-barracks

Kilmuir, Isle of Skye

If you are interested in Flora MacDonald, visit her grave at Kilmuir Cemetery.

The Reluctant Rebel is published by Luath Press.

Conversation