One of Scotland’s most iconic birds, the capercaillie, could be extinct in 20 years. Gayle Ritchie finds out why the bird is struggling to survive – and what can be done.

At 4am, during the coldest part of the night, a strange popping and gurgling noise began in trees high above Patrick Galbraith’s head.

Shivering in a tiny camouflaged hide beneath the canopy of the ancient Caledonian pine forest, Patrick was here to witness something very special – a capercaillie lek – where male birds group together to compete for mates, in the hope that females will be impressed enough to mate with them.

A group of hen “cappers” had shown face nearby the previous night and the local gamekeeper told him there was a good chance they might turn up here tonight to meet the boys and (hopefully) copulate.

Alas, while six males strutted their stuff from dusk until dawn, not one lady graced them with her presence – and that is no laughing matter.

Today, the capercaillie is one of Scotland’s most endangered birds.

A member of the grouse family, adult males are roughly the size of turkeys and, unlike the bullet-like speed of their smaller cousins the red grouse, they have a slower, more ungainly style of flight.

The birds are notoriously reclusive, sheltering in native pinewood forests of the Highlands, venturing out to court at dawn.

It’s estimated there are only around 700 in Scotland, vastly reduced from the early 1990s when there were thought to be 2,200. And there’s also been a marked reduction in the bird’s geographical range.

There are real fears that if the population continues to plummet, capercaillies could become extinct in Scotland within the next two to three decades.

Numbers have dropped because of increased predation from foxes, pine martens and crows, erosion of their habitats, and disturbance from countryside users.

Magical but bleak

Edinburgh-born author Patrick was given special access to a hide in forestry near Aviemore, one of the capercaillie’s last strongholds, to observe a lek.

It was a crucial part of research for his new book – In Search of One Last Song: Britain’s Disappearing Birds and the People Trying to Save Them.

“In order to not disturb the capercaillies I had to be in the hide at 7pm, before they went up to roost,” he explains.

“I couldn’t leave until they’d been on lek until 11am the following morning, so I was there, freezing cold and eating pieces of ginger cake all night.”

Patrick describes the experience of watching the courtship ritual as “incredibly magical”.

First, the males dropped from their roosts, and then he heard them making “otherworldly” bubbling and popping sounds.

“Until around 8am the dominant cock clattered through the undergrowth, rasping and clicking and stopping only briefly to leap into the air, wings beating, like a dance, and puffed-up neck shimmering in the sun,” he recalls.

“The hope is that the hen capper will be out there somewhere, but none came that night. There’s something quite bleak about that. The problem is if they get disturbed on the day of copulation that has a massive impact. It’s a species right on the edge.”

While the estate Patrick was visiting (he wants to keep the exact location secret) boasts more than 30,000 acres of pine forest, making up 9% of the country’s total – ideal capercaillie habitat – and it’s just taken on a second gamekeeper to focus solely on the birds, he says the birds can’t exist “as an island”.

“It’s great if an estate is involved in capercaillie conservation,” he says, “but unless nearby estates are, too, the birds don’t really stand a chance because they need to be able to move from place to place to start a new population.”

Bizarre encounters

Wildlife photographer Ian Hay’s first experience of seeing a capercaillie was in Speyside.

“It had the elegance of a brick when I spotted it flying through a conifer plantation,” he recalls.

A few years later, he came face-to-face with a hen capper in a rather bizarre – and sad – encounter in forestry near the Bennachie Visitor Centre in Inverurie, Aberdeenshire.

“I got word it was hanging around the centre and a group of arachnologists,” says Ian.

“I spent a few hours walking around the area but with no luck until I sat on a picnic bench and started checking emails on my phone. At this point the female capper dropped out of a nearby tree and walked over to me, at one point sitting on my foot! It was a profound and moving experience but a sad one.”

The reason for her friendliness, says Ian, was that she had never seen a male capercaillie and hoped that he was one.

A year later she was captured and taken to a wood with “real” male capercaillies.

“Hopefully she has now discovered the real thing and done her bit to help the species survive,” he adds.

It had the elegance of a brick when I spotted it flying through a conifer plantation.

IAN HAY

Strange tales about confused hen cappers abound, and Ian’s friend was delighted when one started visiting his garden.

“I was quite sceptical – was it really a capercaillie? But he sent me a photo and it undoubtedly showed a female sitting in his workshop between his power tools.”

‘Bird from hell’

Nature writer Jim Crumley will never forget the moment a capercaillie “gatecrashed” his life in Glen Derry in the Cairngorms.

It was more than 35 years ago, at about 2.30am on a spring morning under a full moon.

“I walked deep into a pine forest and clambered into a sleeping bag under the stars about 1am,” Jim recalls.

“At 2.30am I was jerked awake by the sound of bath water running down a plughole. In such circumstances you try to rein in the scattering fragments of consciousness, get over the where-the-hell-am-I moment, and focus on the sound which seemed to be coming from a nearby pine tree.

“The bath water routine degenerated into a recording of a drumming woodpecker fiendishly slowed down and horribly magnified. The only thing that made sense was that I was still asleep and deep in a weird dream.

“It lasted an hour, by which time I had considered then rationalised a handful of possibilities. Finally, there materialised among pine limbs, a silhouette of a bird from hell. But it was just a male capercaillie warming up for the spring rituals of the lek. The image in the tree clarified it: head high, back arched, tail thrown up and curved like a black sunrise.”

The bird eventually flew down to the lekking ground and Jim was able to watch snatches of the ritual, which lasted three hours, through the trees.

“There were at least four cock birds locked into an unearthly dance. Once, a hen bird broke away from the mayhem and headed straight towards me, but a cock bird overtook her and turned her back.

“Then suddenly it was over, the males scattered fast through the treetops, far out over the glen, white wing-bars flashing.”

The image in the tree clarified it: head high, back arched, tail thrown up and curved like a black sunrise.

JIM CRUMLEY

Difficult

Jim says while nothing about a capercaillie’s presence in a pinewood is “ever mundane”, everything about it is “difficult”.

“The capercaillie is in trouble in Scotland,” he laments. “Conservation’s best efforts have not worked well, and if we are honest, our best efforts have not been very good.

“The two-volume Birds of Scotland published by the Scottish Ornithologists Club in 2007 commemorates their extinction thus: ‘Scottish capercaillie were sold in Perth market in 1746, with the last record of endemic birds being of two males shot on the occasion of a marriage celebration at Balmoral.

“During the 19th and 20th Centuries a number of reintroductions occurred, organised by naturalists and shooting interests…’”

The felling of mature woodland in both World Wars destroyed capercaillie habitat, and the population has never truly recovered.

“Naturalist Seton Gordon mentions reintroductions at Taymouth in Perthshire in 1837 from which the birds spread across the Central Highlands and the Cairngorms,” says Jim. “Drummond Hill above Loch Tay was a favourite spot for years.

“Mysteriously, a population established at Tentsmuir Forest in Fife clung on into the 1980s. I presume it was artificially introduced, but I can’t imagine who thought it was a good idea, given the isolated nature of the wood.”

The capercaillie’s critical status in Scotland – now thought to be around 700 birds, maybe fewer – is the subject of much hand-wringing among conservationists, says Jim.

“Apart from removing forestry fences or making them more visible (the birds often collide with them and die), the biggest idea is controlling fox and crow populations, which frankly, is a solution for nothing at all,” he says.

“Before capercaillies were wiped out by people with guns – and when the native forest was a thriving part of our landscape, capercaillies, foxes, crows, wolves, pine martens and much else besides, all thrived in the same landscape.

“It’s intriguing that I could not find a single reference to predation on capercaillies by golden eagles covering the last 70 years. Yet Seton Gordon, in 1955, wrote about it in Scotland, Sweden, Estonia and Switzerland – it’s widespread. No one suggests controlling golden eagles to protect capercaillies.”

The capercaillie’s problem, says Jim, is us: “In particular, historically, we have liked to shoot them.

“More recently, we have destroyed its habitat, and even now, when an awareness of the value of native woodland is higher than at any time in the last 100 years, that habitat is still a thing of fragments.”

Jim suggests the “first priority” of the Cairngorms National Park should be to encircle the mountain massif with a continuous forest, and restore the treeline.

And he says that Highland Perthshire, the capercaillie’s other comparative stronghold in the last 100 years, is “beset by some of the worst excesses of the wrong kind of land ownership priorities”, especially if you are the largest grouse in the land.

With recent talk of a new national park or parks in Scotland, Jim suggests the one that uses Highland Perthshire and east Argyll – Rannoch, the Black Mount, Glen Orchy, Loch Etive – to link Scotland’s two existing national parks is the one that “makes sense”, but “only if continuous expansion of native forest is a fundamental component, and biodiversity its watchword”.

He adds: “Then we might begin to repay the centuries-old debt we owe to capercaillies in particular and the land in general.”

Threat to all-comers

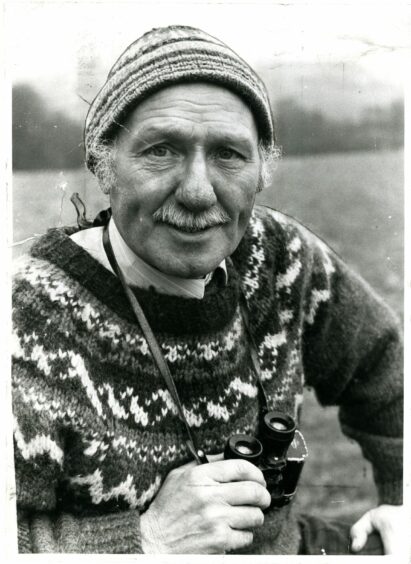

Adventurer, writer, climber, broadcaster and naturalist Tom Weir wrote about filming a male capercaillie in Glen Lyon, Perthshire, in his 1980 book, Tom Weir’s Scotland.

The chapter is titled Capercaillie Aggression and focuses on the bird’s notable aggression in the breeding season. The cock bird who was the villain of Glasgow-born Tom’s captivating story had taken to attacking human instead of rival cocks. Sadly he died when he attacked a Land Rover, but only after he had drawn blood from ornithologists galore.

Armed with his cine-camera and a warning from the gamekeeper, Tom set off towards a distant heathery hump.

“In a trice I was watching through the viewfinder a great bird climbing fast up the knoll, its legs moving in a mechanical glide over the ground like a life-sized clockwork toy,” wrote Tom.

“It stopped just as its great hooked beak and hanging ruff of feathers filled the frame, and I had just time to put up my boot as it leapt, colliding against it, and began biting at the rubber sole. Then, as if dignity has asserted itself, it threw itself back, stood tall, and virtually blew itself up as I watched.

“The neck swelled, the tail became a huge fan, the red wattle round the eye enlarged, the feathers of the neck projected. Head up and wicked beak open, its display was an unmistakable threat to all-comers.”

Tom resumed filming when the bird leapt again, ramming itself against his boot once more. Involuntarily he stepped back and as if taking his cue, so did the bird. He then played a game of “advance and retire” with the capercaillie, describing it as great fun.

Long-term survival?

The capercaillie became extinct in the UK in the late 18th Century but was reintroduced successfully to Scotland in the middle of the 19th Century.

A recent study from a sub-group of the NatureScot Scientific Advisory Committee, warned that current breeding success appears to be too low to allow recovery of the population.

It said “renewed intensive measures” are needed, focusing on options that will improve the survival of eggs and young chicks.

The report warned that any delay in enacting these “might result in the population declining to a point where extinction becomes inevitable.”

Measures proposed include controlling predators such as crows, foxes and pine martens, and “diversionary feeding” by offering the birds alternative food during the breeding season.

The report also suggested creating refuges for capercaillies to minimise disturbance, while survival of adults would be enhanced with more work to mark or remove deer fences, which can cause injury or death to birds in flight.

NatureScot and the Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) are drawing up options to improve prospects for capercaillie.

Grant Moir, chief executive of CNPA, said: “Capercaillie are an iconic species and we have been working hard with partners through the Cairngorms Capercaillie Project to help ensure their long-term survival.”

In Search of One Last Song

In his new book, In Search of One Last Song, Patrick Galbraith travels the country in search of 10 of our most endangered birds. The encounters he has, including holding a nightingale in the palm of his hand, tagging a hen harrier, and sleeping out on a capercaillie lek, are extraordinary, but the people he meets on the way – an eclectic group who have devoted their lives trying to save these birds – are just as remarkable.

“A lot of it is about the way that birds inspire senses of places and become part of people’s identity,” he says.

“When these birds go, it’s a sort of existential loss. I was keen to show people through this book the way birds inspire so much of our culture and wanted to create a picture of the void that will be left when they go.”

Conversation