From where I sit, dictating these words to my secretary, I can look up and see three cheaply framed prints on the wall in front of me, here at Wit’s End, ma hoose.

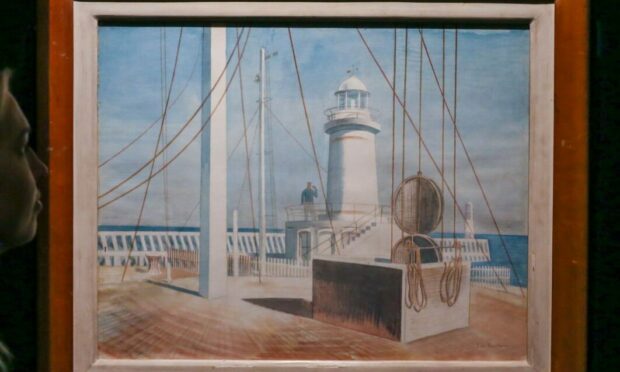

Sometimes, I get lost in these prints. They are calming, dreamy. They depict unimportant events: a man with his spade in a large garden in the country; a red van approaching a junction on a rural road; a lone figure with his back to us, half-way down a narrow lane fringed by high hedges.

If forced by aesthetically inclined thugs to say what I find most important in art, I would say: “I dinnae ken, ken? But I suppose it might be … stillness.”

I don’t know what I mean by that, but suspect it might be right profound, so will just leave it there for you to ponder.

‘I thought I had him to myself’

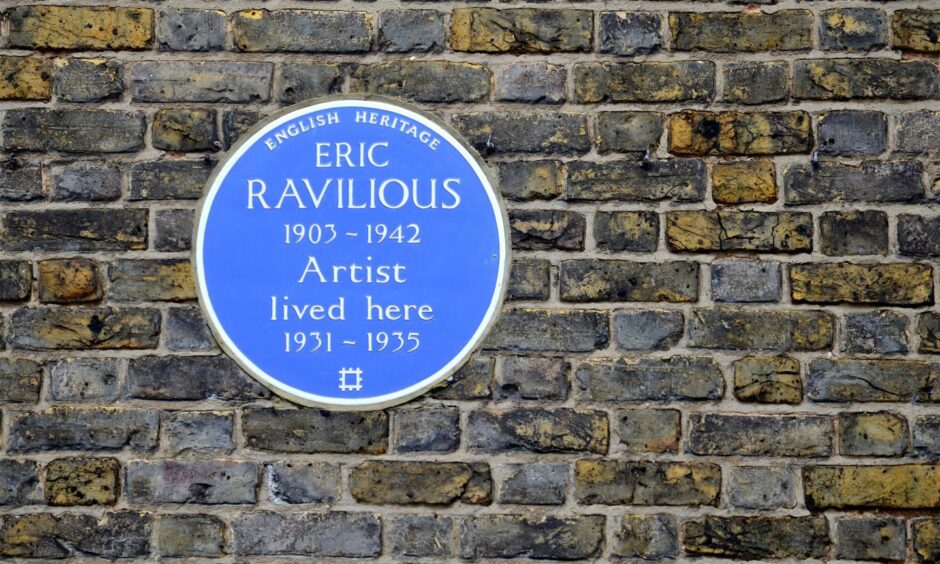

The prints are from paintings by Eric Ravilious, and I thought I had him all to myself. Does that ever happen to you: the experience of shock when you discover something you like, and thought rather niche, is actually quite popular?

It happens, to me, with prosaic items such as medicines or internet things or planned bucket list dreams.

Like a hurl on the Hurtigruten, a boat trip up the west coast of Norway, actually the only thing on my bucket list.

You think they’re personal to you, and then find a rabid mob onto the same things. I usually discover this through television adverts, which I rarely see, maybe once every six months.

A certain Englishness…

I mention all this in relation to Ravilious, whose work I discovered a couple of years ago. I’ve got a book about him and everything.

They say his work depicts a certain Englishness, which is probably true, in the sense of rolling landscapes, gardens, greenhouses.

There’s the tiniest whisper of melancholy too and often, as in the pictures before me, a cloudy greyness (this was pre-global warming).

A new film

The reason I mention this is that Ravilious – my Ravilious – has recently been the subject of a film.

It’s called Eric Ravilious: Drawn to War, and the reason for the title is that he became an artist with the forces during WWII.

Indeed, he was the first such to die on active service when a plane on a search-and-rescue mission crashed into the sea off the coast of Iceland.

He was only 39. His body was never recovered.

Released at the start of this month, the film, directed by Margy Kinmonth and featuring contributions by Alan Bennett, has been described (in the Guardian newspaper by Tamsin Greig, who provides the voice of Ravilious’s wife) as “tender and elegiac”.

All art is personal

I haven’t seen it, mainly on account of the lack of cinemas where I live, but I will one day. Of course, all art is personal. Your Ravilious may not be mine.

Robert Macfarlane, who featured Ravilious in his bestselling book The Old Ways – about the ancient, secret paths of Britain – identifies in him “this old, fatal love for the landscape”. The word “fatal” is discombobulating.

I do find my love of trees, sea, sky, meadows peculiar sometimes. Where does it come from? Cultural conditioning, atavistic memory, ingrained Platonic ideal? I dinnae ken.

It makes for good art, though.

Conversation